Crossword Solution and Problem

I got an email last week pointing out that I had won another prize in the Times Literary Supplement crossword competition 1565. They have modernised at the TLS, so instead of sending a cheque for the winnings, they pay by bank transfer and wanted to check whether my details had changed since last time. You can submit by email nowadays too, which saves a bit in postage.

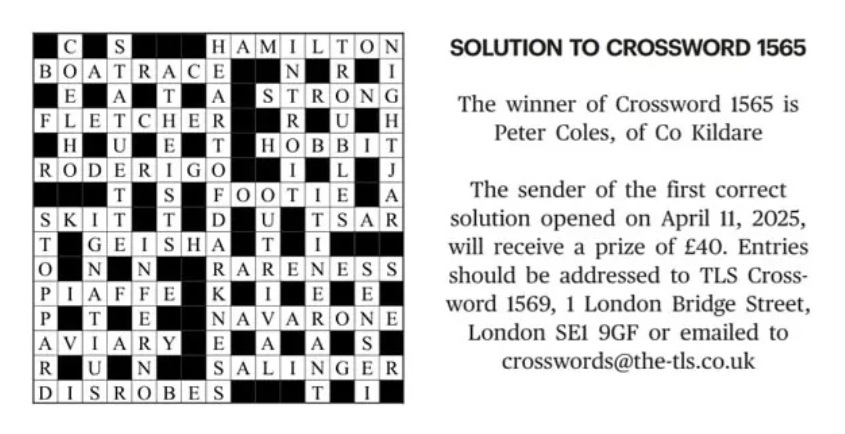

Anyway, I checked this week’s online edition and found this for proof:

I checked when I last won this competition, which I enter just about every week, and found that it was number 1514, almost exactly a year ago. There are 50 competitions per year rather than 52, because there are double issues at Christmas and in August, so it’s actually just over a year (51 puzzles) since I last won. I’ve won the crossword prize quite a few times but haven’t been very careful at keeping track of the dates. I think it’s been about once a year since I started entering.

All this suggested to me a little problem I devised when I was teaching probability and statistics many years ago:

Let’s assume that the same number of correct entries, N, is submitted for each competition. The winner each time is drawn randomly from among these N. If there are 50 competitions in a year and I submit a correct answer each time, winning once in these 50 submissions, then what can I infer about N?

Answers on a postcard, via email, or, preferably, via the Comments!

March 22, 2025 at 7:02 pm

N=50?

March 22, 2025 at 7:16 pm

Does it have to be exactly 50?

March 23, 2025 at 9:13 am

Only in the limit of repeating over many years. Otherwise the inference will peak at 50 but be quite broad.Reading the question as winning one time and not winning 49 times, the likelihood is a binomial of 1 event in 50 trials with p = 1/N. Which simplifies to the Poissonian probability of 1 event where the expectation is 50/N. Then multiply by your favourite prior.

March 23, 2025 at 11:37 am

CoNgratulatioNs!

March 23, 2025 at 6:52 pm

The likelihood function (probabilty of winning exactly once in 50 entries) is L(N) = 50 (N-1)^{49}/N^{50}. This has a maximum at N = 50 but is quite broad as Prasenjit Saha says.

The distribution is also quite asymmetric — as it must be, since N is positive. For instance, the likelihood drops to half its peak at N = 19 and N = 214.

Since we’re all good Bayesians here, we should multiply the likelihood by a prior to get a posterior probability distribution on N. A prior that’s uniform in N leads to a posterior that doesn’t converge — the likelihood goes like 1/N for large N.

Maybe we should pick a prior that’s uniform in log(N) then. (I always find the choice of a “natural” prior to be a bit confusing, to be honest.) In that case, the posterior probability peaks at N=26. The 95% credible region actually extends all the way from N=6 to N=975 or so, so you really can’t say anything terribly precise based on one batch of 50 submissions.

March 23, 2025 at 9:55 pm

I think a uniform prior is fine, actually, because it must be truncated – there can only be a finite number of potential solvers. I would cut it off at the circulation figure (around 50,000) or if you want to be ultra-conservative, the number of people on the planet!

March 24, 2025 at 1:35 pm

Yes, I agree. Then the answer does depend on the choice of cutoff, but since the divergence is only logarithmic it doesn’t change all that much.

March 24, 2025 at 2:54 pm

If I’m not mistaken (and I certainly may be), the 95% credible region with a uniform prior with a cutoff at 50000 goes from N=7 to about 36000. Doubling the maximum in the prior nearly doubles the upper limit, so the dependence of the result on the choice of cutoff isn’t all that weak.

March 24, 2025 at 4:24 pm

This type of problem is useful for illustrate the fact that quoting the “best estimate” of N is rather misleading