How to be a better PhD supervisor

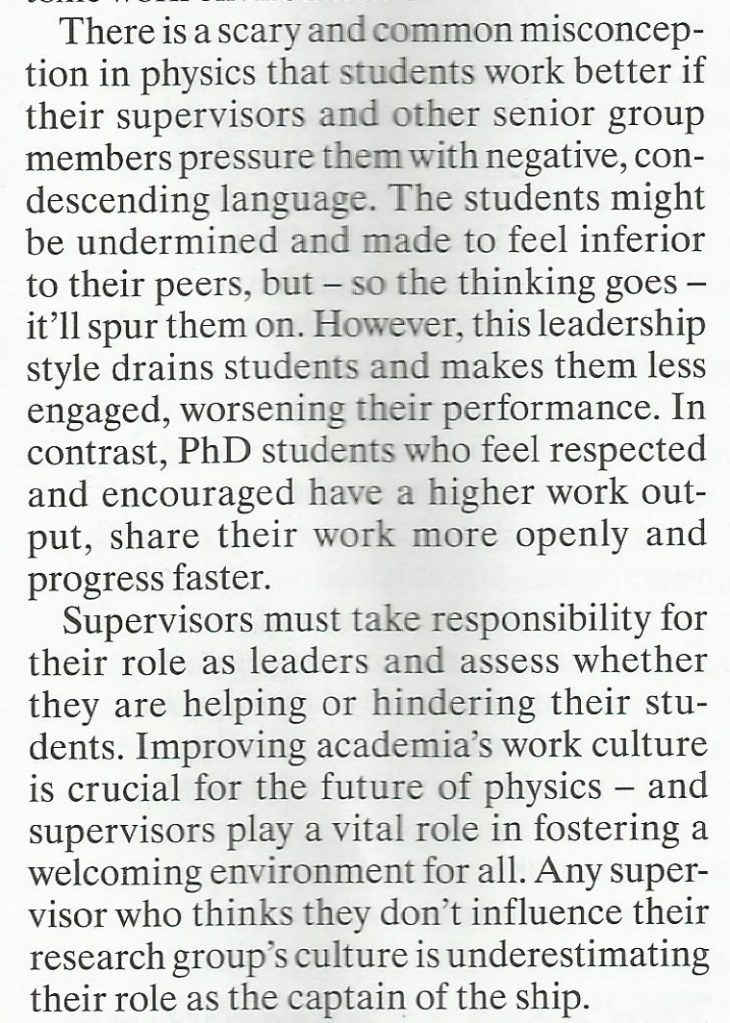

The text for this Sunday’s sermon is provided by a piece by a Danish PhD student called Rikke Plougmann in the latest Physics World entitled How to become a better supervisor. The article is quite interesting, though I was a bit alarmed by the first of the two paragraphs here:

While it certainly is “scary” I don’t think the “misconception” described in the first paragraph is “widespread”, or at least I sincerely hope it isn’t. I think any supervisor who behaves in such a way towards their research students shouldn’t be allowed to have any! Does your supervisor use “negative, condescending language”? If so I think you should get a new one!

Whether or not the first paragraph is accurate, the second definitely is. It is important for a supervisor (and the rest of a research group and the rest of a department and indeed the whole institution) to try their best to create a welcoming environment for all.

I have written several times on here about my own experiences as a PhD student, most recently here. I have written much less about my experiences as a supervisor. That’s partly because I don’t feel comfortable writing about what I think should really be confidential matters relating to PhD students and partly because each student-supervisor relationship is different.

I certainly don’t think I’m any sort of role model as a PhD supervisor. Among many other failings, I have let my students down at various times when I’ve been mentally unwell and/or when struggling with workload. But I’ve always tried to be friendly and supportive, and encouraged students to look after their work-life balance.

Other than that, it has always seemed to me that it is important for a supervisor to create a healthy working relationship. It’s not simply about training an early-career researcher. The fact of the matter is that when you take on a research student it’s because there is a project you think should be done but you’re not able to do it on your own. The student should realize that their work is not some sort of prolonged test but is highly valued as an essential contribution to a project. In other words, you need the student. I have known some supervisors to act as if they are doing students a favour by taking them on, when the reality is the other way round.

Another thing that I think a supervisor should do is make it clear that they do not have a monopoly on wisdom. Students should be encouraged to question what the supervisor suggests. I always feel I’m succeeding as a supervisor when a PhD student has the confidence to say something like “I thought about what you suggested and decided it wouldn’t work so I did this instead….”

Certainly, by the end of a PhD, the student should know more about the topic than their supervisor. At the beginning, though, the supervisor will know more and it is more of a teacher/pupil relationship then. Managing the transition from that to the equal partnership it should become is tricky as it depends on individual personalities, and it doesn’t always work out. That’s not always the fault of the supervisor. On the other hand, recognizing that’s where you should be headed is at least a start.

Above all, a supervisor should try the best they can to enable the student to enjoy their PhD. I certainly enjoyed mine and I am immensely grateful to my supervisor, who is alas no longer with us, for being so kind and supportive to me during the difficult times as well as giving me such interesting projects to do.

I’m aware this is all rather vague so I’d welcome any comments either from students about how they feel their supervisor might be better or from supervisors with advice to others. The box below is at your disposal.

July 25, 2022 at 11:58 am

I agree with all you write here, but I think there is one, maybe two, complications that face supervisors the pays to spell out: the slow change in what words/phrasings/styles are considered acceptable, and the inherently very multi-cultural environment that astrophysicists and our ilk work in.

To take the latter first: not only are people different, and substantially so, but also unwritten cultural mores instilled very early on, are often influencing our reactions to others. Thus I think also the first phase of “teacher/pupil” is a tricky one to navigate. As a very trivial example: I am used to a very flattened hierarchy from growing up in Norway and I still, after many years, feel awkward when people address me formally, using professor, last name etc, but likewise it is also become very clear that some people feel awkward in adopting a familiar form of address. Thus while early on I would often insist that ‘Jarle’ is fine, I have long since stopped that and tell people once and never again.

Likewise some people prefer very direct feedback, while others prefer a more circumspect way of discussing results (both on the giving and receiving end). And here this connects naturally to my first point: the way we use language always changes, and the way feedback is couched is not immune to this, so what a student (like myself) would have considered acceptable 20 years ago might be construed as offensive today.

As supervisors I do think we are obliged to be sensitive to these aspects, but it is hard when you are both second-language speakers, with a potentially significant cultural gap between you. And some people are simply better at this than others.

So my 2cs, is that it is important to talk frequently, and not only about science, early on in a supervision relationship to try to establish a common ground. But while two-way communication is important (and occasionally hard to achieve) the responsibility is primarily on the supervisor to adapt – we have after all usually supervised several students while the students probably are meeting their first PhD supervisor.

July 25, 2022 at 12:07 pm

Interesting points. I have to say the first one never occurred to me. Students from undergraduate to postgraduate have always just called me Peter…

July 25, 2022 at 6:44 pm

The highlight of any PhD supervision is when the student first proves the supervisor to be wrong. That is the level we would like them to reach and what we train them for, but of course the supervisor may have to swallow some pride on the way. The student will become a collaborator and eventually a competitor. Being a PhD student can be extremely stressful. And living in poverty for 3 or 4 years is also not easy.