Modern Ireland 1600-1972 by R. F. Foster

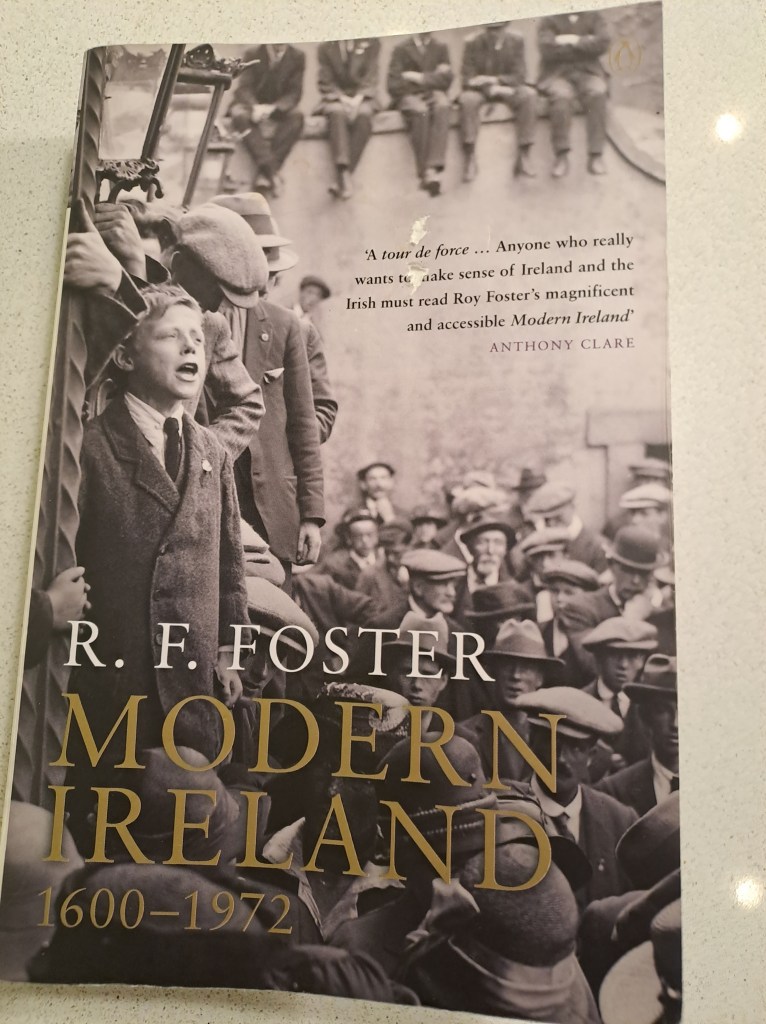

My attempt to catch up with a backlog of reading while on sabbatical has now brought me to Modern Ireland, by R.F. Foster, the paperback version of which, shown above, I bought way back in 2018 but have only just finished reading. In the following I’ll describe the scope of the book and make a few observations.

The book was first published in 1988 so it obviously can’t deal with more recent events such as the Good Friday Agreement. The narrative stops almost 50 years ago in 1972, the year of Bloody Sunday and just before Ireland joined the European Economic Community in 1973, but since it starts way back in 1600 one can forgive Roy Foster for not covering such recent events. The start is in what is usually termed the early modern period, but if truth be told much of Irish society at that point was still organized on mediaeval lines.

To set the scene, Foster starts with a description of the three main sections of the population of Ireland in 1600. These were the (Gaelic and Catholic) Irish, the “Old English”, descendants of the 12th Century conquest of part of the country, who were also Catholic, and the Protestant “New English” who arrived with the Tudor plantations. There were tensions between all three of these groups.

The rest of the book is divided into four parts, roughly one per century: Part I covers the continued Elizabethan plantation of Ireland, rebellions against it, the devastation caused by Cromwell’s so-called “pacification”, and the Penal Laws that basically outlawed the Catholic faith. In Part II Foster discusses a period often called The Ascendancy which showed the consolidation of power in the hands of a Protestant – specifically Anglican – ruling class, though there was a sizeable community of non-conformist Protestants, chiefly Presbyterians, who were regarded by Anglicans with almost as much suspicion as the Catholics. This Part ends with yet another failed rebellion, involving Wolfe Tone and the United Irishmen, against the backdrop of the French revolution. Up until the Act of Union of 1800, Ireland had its own Parliament; after that Irish MPs were sent to the House of Commons in Westminster. The century covered by Part III includes the Irish Famine, rising levels of rural violence, and issues of land reform, and various attempts to deliver some form of Home Rule; it ends with Charles Stewart Parnell. Part IV covers the Easter Rising, War of Independence, Civil War, Partition, the creation of the Irish Free State, and the eventual formation of the Irish Republic. A running theme through all four Parts is a recognition of how historical forces – and not only religion – shaped Ulster in a different way from the rest of Ireland.

As I’ve said before on this blog, it disturbs me quite how little of this history I was taught at school in England so I found it valuable to read a detailed scholarly work whose main message is that everything is much more complex than simple narratives – those peddled by politicians, for example – would have you believe. This is primarily a revisionist history, calling much of received wisdom into question. That said, it’s probably not the best book for a newcomer to Irish history. Foster does assume knowledge of quite a few of the major events and, while reading it, I did have to look quite a few things up. Much is said in the jacket reviews of the author’s writing style. To be honest, I found it sometimes rather mannered and self-conscious, though with some enjoyably arch humour thrown in for good measure. It’s thoroughly researched, as far as that is possible when primary sources are sketchy and contemporary records usually written by someone with an axe to grind. It does seem to rely mainly on documents written in English, however, so one might argue that introduces quite a bias. I gather that there is much greater emphasis among contemporary Irish historians on records written in Irish (Gaelic).

The book is rather heavy on footnotes, too. Usually I dislike these, but in this case they are mostly little biographical sketches of important figures which would have disrupted the flow if included in the main text, and I found many of them valuable. Just to be perverse, I have to say I liked his liberal use of semicolons. Though dense, the books is as accessible as I think a scholarly work can be and although I am not so much a scholar of history as an interested bystander, I learnt a lot. It also made me want to learn more, especially about the period between the death of Parnell in 1891 and the Easter Rising of 1916.

It seems apt to finish with an excerpt that illustrates a theme that crops up repeatedly during the 23 chapters of the book:

Irish history in the long period since the completion of the Elizabethan conquest concerned a great deal more than the definition of Irishness against Britishness; this survey has attempted to indicate as much. But that sense of difference comes strongly through, though its expression was conditioned by altering circumstances, and adapted for different interest-groups, as the years passed. If the claims of cultural maturity and a new European identity advanced by the 1970s can be substantiated, it may be by the hope of a more relaxed and inclusive definition of Irishness, and a less constricted view of Irish history.

Modern Ireland, R. F. Foster, p596

I hope that too. It may even be happening.

October 30, 2023 at 9:54 pm

The history before 1600 is worth mentioning. Henry II of England had invaded Ireland in the 12th century, and whether the only English Pope licensed him to do so or not (and correspondingly whether or not the asserted papal bull is a forgery) remains a matter of controversy.

Following this invasion, London had control, via Dublin, of varying amounts of Ireland. Many English overlords ‘went native’, and by Henry VIII’s time little practical English power remained there. Henry VIII had been determined to impose English law and a centralised government throughout Ireland, extending from the relatively Anglicised parts to the areas controlled by Gaelic chieftains and administered under Brehon Law – traditional Irish tribal law. His daughter Elizabeth I ramped up his military campaign and replacement of the Gaelic aristocracy (by ‘plantation’ of an English one), almost bankrupting England in the process. The last stand of gaelic Ireland was the Battle of Kinsale in 1601; a few years later the senior gaelic aristocracy fled to seek allies in Catholic Europe, the ‘flight of the Earls’, but they never returned. From 1609 James VI of Scotland and I of England began the ‘plantation’ of Ulster by protestant Scots, his own kinsmen.

How many of the presbyterians you mention were Scots and how many English, Peter? Following the Reformation, the Scots were always more committed to presbyterianism than the English.

The factions in the fighting in Ireland in the 1640s, in combination with their interacxtions with the power across the Irish Sea, makes an incredibly complex episode.

October 30, 2023 at 10:08 pm

I don’t know the exact proportion but I think an overwhelming majority of Presbyterians were of Scottish origin, and most settled in Ulster.

They were not the only non-conformists (“Dissenters”), though. There have been many notable Quakers in Irish history, for example.

It’s worth mentioning that local rebellion led by ‘Silken Thomas’ Fitzgerald of Maynooth against English rule was one of the factors that provoked Henry VIII to start the “reconquest”.

The Elizabethan plantation was indeed somewhat incompetently managed.