Mozart and Bruckner at the National Concert Hall

I was worried I might have to miss last night’s concert by National Symphony Orchestra Ireland conducted by Anja Bihlmaier at the National Concert Hall. I bought the ticket some weeks ago and was looking forward to it, but I had been a bit unwell earlier in the week and didn’t want to go only to cough all the way through, possibly infecting others on the way. By Friday afternoon, however, I felt a lot better and took the decision to go for it. I’m very glad I did because I enjoyed the music enormously and didn’t cough or sneeze once!

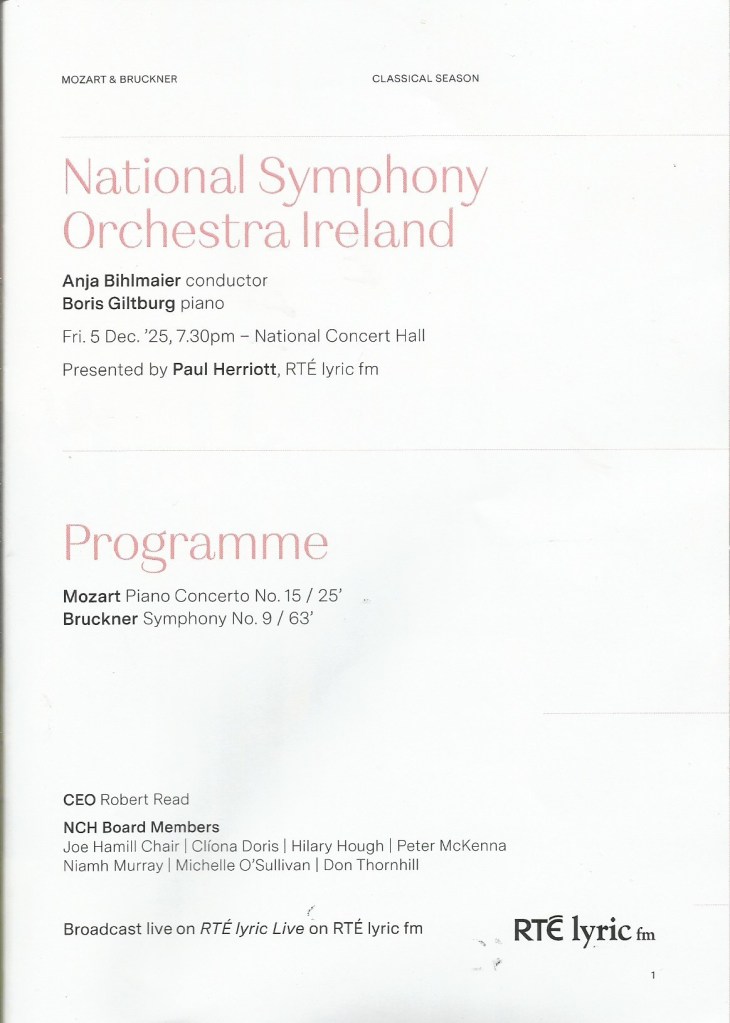

There were only two items on the menu, another pairing of Mozart and Bruckner.

In the first half we heard the Piano Concerto No. 15 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart played by Boris Giltberg. This piece was written in 1784 when the composer had reached the ripe old age of 28. It’s an enjoyable and entertaining piece, not perhaps as profound as some of the later piano concertos (Mozart wrote 27 altogether), but well worth listening to. It’s also regarded as one of the most difficult to play, though Boris Giltberg made it look easy enough and was clearly enjoying himself while he played it as I’m sure did the composer when he performed it for the first time in Vienna. The three movements follow a standard fast-slow-fast pattern; the last being a sprightly Rondo, part of which features in the soundtrack of an episode of Inspector Morse: Who Killed Harry Field?

After generous applause, Giltberg returned to the stage to play a very solo encore piece. I didn’t recognize it, but someone I know who was there told me it was by Robert Schumann but didn’t know the name. When I got home I spent a good half-hour going through recordings until I finally identified it as the Arabeske in C Major. Anyway, it was a very nice way to send us into the wine break.

After the interval we had Anton Bruckner‘s monumental Symphony No. 9, which was unfinished at Bruckner’s death in 1896. Insufficient material was recovered after the composer’s death to enable a reconstruction of the missing 4th movement, so this work is generally performed in its incomplete state with only three movements. Even so, it’s an immense work in both length and ambition, lasting over an hour in performance and calling for a large orchestra.

The majestic first movement (marked Feierlich, Misterioso; solemn & mysterious) with its soaring themes and thunderous climaxes always puts me in mind of a mountaineering expedition, with wonderful vistas to experience but with danger lurking at every step. At times it’s rapturously beautiful, at times terrifying. It’s not actually about mountaineering, of course – Bruckner meant this symphony to be an expression of his religious faith, which, in the latter years of his life must have been pretty shaky if the music is anything to go by.

The second movement (Scherzo) is all juddering rhythms, jagged themes and harsh dissonances reminiscent (to me) of Shostakovich. It alternates between menacing, playful and cryptic; the frenzied animation of central Trio section is especially disconcerting.

The last movement (Adagio) begins restlessly, with an unaccompanied violin theme and then becomes more obviously religious in character in various passages of hymn-like quality, still punctuated by stark crescendi. In this movement Bruckner doffs his cap in the direction of Richard Wagner, especially when the four Wagner tubas appear, and the movement reaches yet another climax with the brass bellowing out the initial violin theme. This dies away and the movement comes to an unresolved, poignant conclusion. With a long pause in silence as if to say “that’s all he wrote”, the concert came to an end.

Although I’ve loved this work for many years I’ve only ever heard it once before in concert. The live performance definitely adds other dimensions you will miss on a recording and I enjoyed it enormously. For one thing you can see how hard the musicians – especially the cellos and basses – have to work. The sight of a large symphony orchestra working together to produce amazing sounds is quite something.

The National Symphony Orchestra Ireland may not be the Berlin Philharmonic but I was generally very impressed, there was split note in the brass section near the end, but this was a minor blemish. The performance was very warmly received by the audience. The NCH wasn’t full, but it was quite a good attendance.

That’s not quite the end of my concert-going for 2025. I’m off to Messiah next week. Well, you have to, don’t you? It’s Christmas..

December 6, 2025 at 7:32 pm

That must have been a very enjoyable concert.

I love Bruckner’s Ninth Symphony, and adore the recording by the Vienna Philharmonic and Carlo Maria Giulini.

December 6, 2025 at 9:48 pm

My favourite (so far) is the one by the Berliner Philharmoniker with Herbert von Karajan

December 6, 2025 at 10:43 pm

Ah, yes, I’ve got the Karajan Berlin Philharmoniker set.

Many conductors perform the three-movement symphony as though it was intended to have three movements only, pacing the piece so that the end seems natural and final. I really like it that way, even though it’s nothing like what Bruckner imagined.

December 8, 2025 at 9:48 am

It’s common to describe Bruckner’s 9th as “unfinished”, as you do – but this statement is misleading. For years, I read such things and assumed that Bruckner had only created a few partial sketches for elements of a finale – but actually the entire movement was complete in outline and fully orchestrated in many parts. Tragically, it seems that souvenir hunters took pages of the manuscript from Bruckner’s rooms after his death. A number of these turned up over subsequent years, and together with what remained unstolen, various reconstructions of the whole movement have been attempted. The amount of material available is colossal: over 1000 pages of manuscript (see https://www.opusklassiek.nl/componisten/bruckner_symphony_9_finale_wc_spcm.pdf). From this, a clearly shaped movement can be discerned, although fitting the pieces into their correct order is the sort of crossword puzzle that you would appreciate, Peter. In the most common reconstruction, there are 647 bars of music: 208 fully scored and untouched, and of the remainder, the editors composed just 37 to fill gaps between sketches that needed orchestration.

So this is hardly “unfinished”. Whether the music is of the quality of the first 3 movements can be debated. It is known that Bruckner had physical and mental difficulties in this final phase of composition, and parts of the finale have a disturbing air that surely reflects this struggle. The movement feels like it goes off in new directions, and I wouldn’t claim that it makes a capstone to the 9th in the way that the finale of the 8th absolutely does; but even as a piece in its own right, it demands to be heard. This is the most successful performance I know: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DAaYJta8Hng. The passage between 4m30 and 6m45 is as great as anything Bruckner wrote, and I’m deeply grateful to the musical detectives who provided us with the chance to hear it in context.

December 8, 2025 at 10:07 am

According to the programme notes for Saturday’s concert:

I wonder if there are quotations from or references to the Te Deum in any of the sketches?

I also read that it took Bruckner SIX YEARS to produce a version of the first movement he was happy with…

December 8, 2025 at 10:18 am

I don’t think the Te Deum suggestion was anything other than a statement of desperation that Brucker was worried that time would run out. But the music of that piece is echoed in many of his compositions, and indeed you can hear the opening of the Te Deum straight after the passage I highlighted, at 6m50. But I do urge you to listen to the previous section from 4m30 in particular.