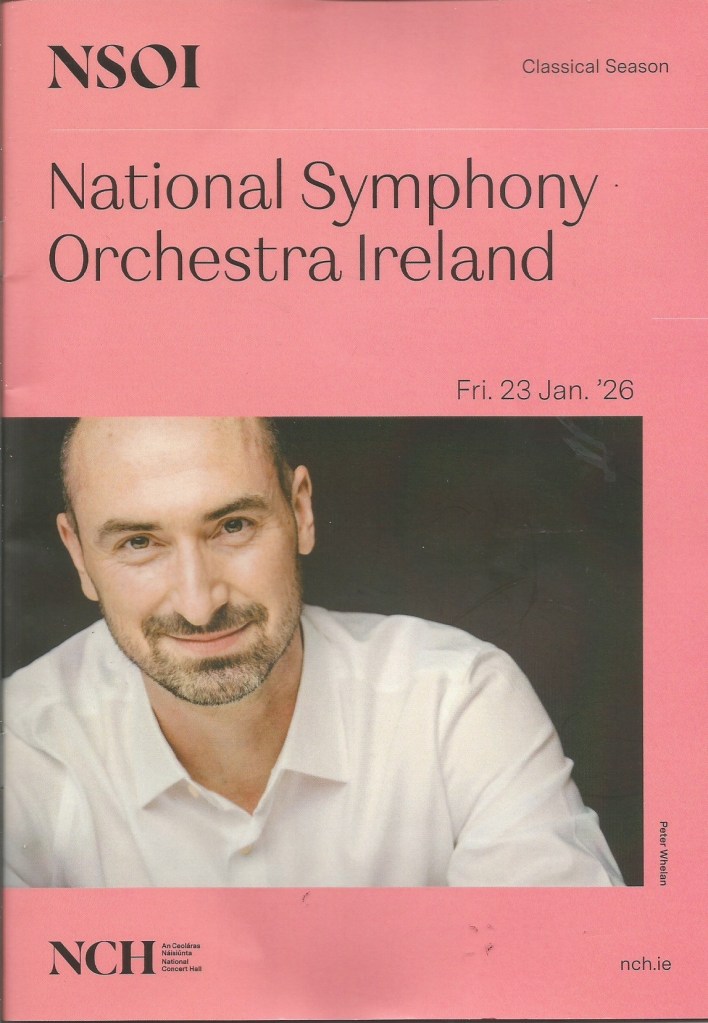

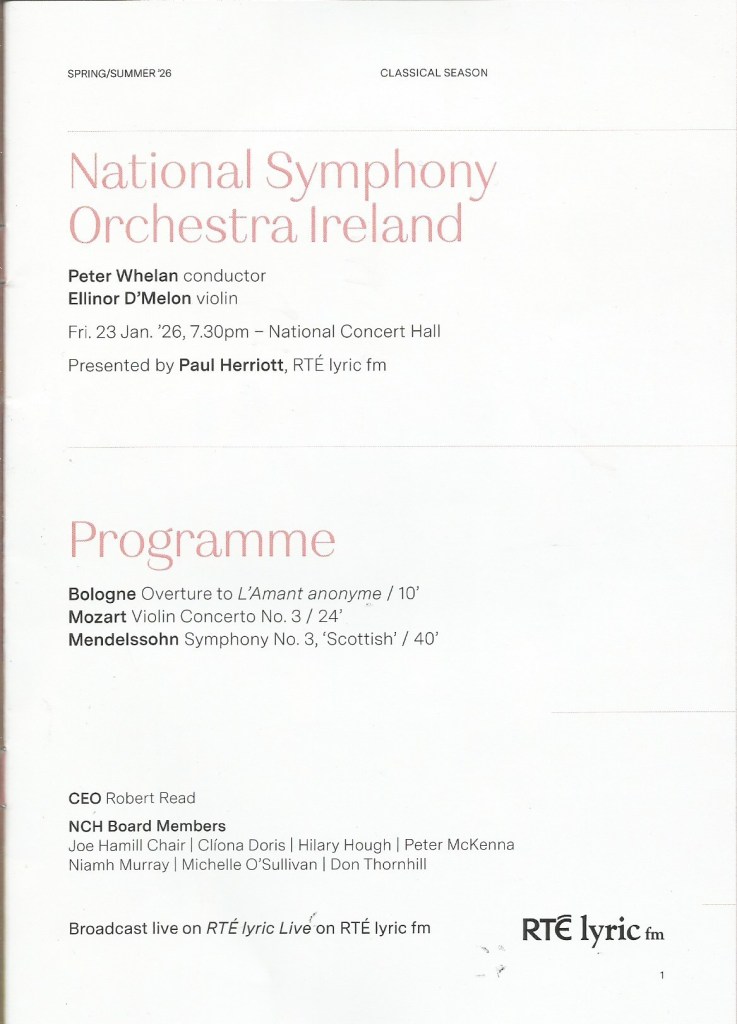

Last night I went to another concert by National Symphony Orchestra Ireland at the National Concert Hall in Dublin. This performance was conducted by NSOI’s new “Artistic Partner” Peter Whelan, shown on the programme cover above. The NCH was by no means full, which was a shame, but the concert was warmly appreciated by those of us there in the audience and no doubt by those listening on the radio.

The first item on the agenda was a new one to me, the overture to the Opera L’Amant Anonyme by Joseph Bologne who went by the title Chevalier de Saint-George. He was born in Guadeloupe; his father was a plantation owner and his mother a slave; Saint-George was the name of his father’s plantation. He became an accompished musician, composer and soldier and a member of the Louis XVI’s personal bodyguard. The music we heard is clearly of the same world as Mozart (of whom Bologne was a contemporary) and very enjoyable to listen to. I wonder if we’ll ever get the chance to hear the whole Opera?

After that – and a long pause before she came on stage, that made me worry that something was amiss – we heard Ellinor D’Melon playing the Violin Concerto No. 3 in G Major by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, written when Mozart was only 19. This is a lovely piece and was played very nicely by Ellinor D’Melon. Apparently Albert Einstein – himself a keen amateur violinist – said that the second movement Adagio “seems to have fallen straight from Heaven”. It is indeed beautiful to listen to, and does have a sense of unity about it that makes you think it must have been conceived and composed in one go. The play Amadeus seems to have been responsible for perpetuating the idea that Mozart often composed in his head, then wrote the results out without corrections or revisions. That is largely untrue, but it is true that he could construct complex sections in his mind’s ear before setting them down on paper. If he did ever compose a piece entirely from start to finish, then the 2nd movement of this Concerto would be it.

(I can’t resist adding an anecdote suggested by this. A while ago I had to arrange a special sitting of a class test for a student who, for good reasons, couldn’t take the assessment with the rest of the class. I wrote a different paper and invigilated the student myself; there were just the two of us in the room for the test, which was to last 50 minutes. Not anticipating any difficulties I sat at a table in the corner and got on with other stuff. About 15 minutes in, I was concerned that the student hadn’t written anything at all; he seemed just to be reading and re-reading the paper. The questions were not meant to be all that difficult, so it surprised me that the student appeared to be struggling. I didn’t interrupt though. Then, about 5 minutes later the student sat up, grabbed a pen and started to write. Not more that 10 minutes after that he announced he had finished and handed me his script. It contained a perfect answer to everything that had been asked, no corrections or crossings out, and it took up less than one page of A4. I was impressed.)

After the wine break we heard the Symphony No. 3 in A minor (“Scottish”) by Felix Mendelssohn. Inspired by a visit to Scotland in 1829 – the first movement was actually composed that year in Edinburgh – it wasn’t completed until over a decade later and should probably be No. 5, but who’s counting? I’ve never really found it very Scottish, actually, but that doesn’t matter either.

It’s a piece consisting of four movements, with little or no break between them. The first movement starts with a slow theme, like a hymn, but then becomes much more reminiscent of the Hebrides Overture Mendelssohn composed in 1830. The landscape of the other three movements is very varied, sometimes cheery, sometimes lush, sometimes tempestuous. The final movement Allegro Vivacissimo has a marking guerriro (“warlike”), which in parts it is, but it also has calmer and more reflective passages before the rumbustious finale. I suppose many people consider Mendelssohn a bit Middle-of-the-Road, but I always find his music very pleasurable and this was no exception.

I always enjoy watching the musicians in these concerts, and could see last night that they were all enjoying themselves hugely. I’d like to single out the sole member of the percussion section, Tom Pritchard on timpani. He had to work hard for nearly all of this performance, as the timpani are kept very busy this work, and did an excellent job.