It’s Friday afternoon at the end of Induction Week here at the University of Sussex. By way of preparation for lectures proper – which start next Monday – I gave a lecture today to all the new students in Physics during which I gave some tips about how to tackle physics problems, not only in terms of how to solve them but also how to present the answer in an appropriate way.

I began with Richard Feynman’s formula (the geezer in the above picture) for solving physics problems:

I began with Richard Feynman’s formula (the geezer in the above picture) for solving physics problems:

- Write down the problem.

- Think very hard.

- Write down the answer.

That may seem either arrogant or facetious, or just a bit of a joke, but that’s really just the middle bit. Feynman’s advice on points 1 and 3 is absolutely spot on and worth repeating many times to an audience of physics students.

I’m a throwback to an older style of school education when the approach to solving unseen mathematical or scientific problems was emphasized much more than it is now. Nowadays much more detailed instructions are given in School examinations than in my day, often to the extent that students are only required to fill in blanks in a solution that has already been mapped out.

I find that many, particularly first-year, students struggle when confronted with a problem with nothing but a blank sheet of paper to write the solution on. The biggest problem we face in physics education, in my view, is not the lack of mathematical skill or background scientific knowledge needed to perform calculations, but a lack of experience of how to set the problem up in the first place and a consequent uncertainty about, or even fear of, how to start. I call this “blank paper syndrome”.

In this context, Feynman’s advice is the key to the first step of solving a problem. When I give tips to students I usually make the first step a bit more general, however. It’s important to read the question too. The key point is to write down the information given in the question and then try to think how it might be connected to the answer. To start with, define appropriate symbols and draw relevant diagrams. Also write down what you’re expected to prove or calculate and what physics might relate that to the information given.

The middle step is more difficult and often relies on flair or the ability to engage in lateral thinking, which some people do more easily than others, but that does not mean it can’t be nurtured. The key part is to look at what you wrote down in the first step, and then apply your little grey cells to teasing out – with the aid of your physics knowledge – things that can lead you to the answer, perhaps via some intermediate quantities not given directly in the question. This is the part where some students get stuck and what one often finds is an impenetrable jumble of mathematical symbols swirling around randomly on the page. The process of problem solving is not always linear. Sometimes it helps to work back a little from the answer you are expected to prove before you can return to the beginning and find a way forward.

Everyone gets stuck sometimes, but you can do yourself a big favour by at least putting some words in amongst the algebra to explain what it is you were attempting to do. That way, even if you get it wrong, you can be given some credit for having an idea of what direction you were thinking of travelling.

The last of Feynman’s steps is also important. I lost count of the coursework attempts I marked this week in which the student got almost to the end, but didn’t finish with a clear statement of the answer to the question posed and just left a formula dangling. Perhaps it’s because the students might have forgotten what they started out trying to do, but it seems very curious to me to get so far into a solution without making absolutely sure you score the points. IHaving done all the hard work, you should learn to savour the finale in which you write “Therefore the answer is…” or “This proves the required result”. Scripts that don’t do this are like detective stories missing the last few pages in which the name of the murderer is finally revealed.

So, putting all these together, here are the three tips I gave to my undergraduate students this morning.

- Read the question! Some students give solutions to problems other than that which is posed. Make sure you read the question carefully. A good habit to get into is first to translate everything given in the question into mathematical form and define any variables you need right at the outset. Also drawing a diagram helps a lot in visualizing the situation, especially helping to elucidate any relevant symmetries.

- Remember to explain your reasoning when doing a mathematical solution. Sometimes it is very difficult to understand what students are trying to do from the maths alone, which makes it difficult to give partial credit if they are trying to the right thing but just make, e.g., a sign error.

- Finish your solution appropriately by stating the answer clearly (and, where relevant, in correct units). Do not let your solution fizzle out – make sure the marker knows you have reached the end and that you have done what was requested. In other words, finish with a flourish!

There are other tips I might add – such as checking answers by doing the numerical parts at least twice on your calculator and thinking about whether the order-of-magnitude of the answer is physically reasonable – but these are minor compared to the overall strategy.

And another thing is not to be discouraged if you find physics problems difficult. Never give up without a fight. It’s only by trying difficult things that you can improve your ability by learning from your mistakes. It’s not the job of a physics lecturer to make physics seem easy but to encourage you to believe that you can do things that are difficult.

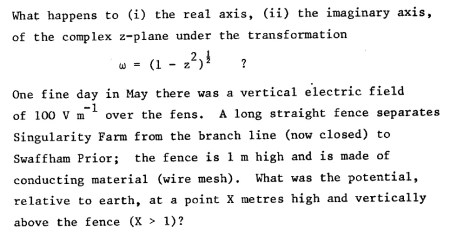

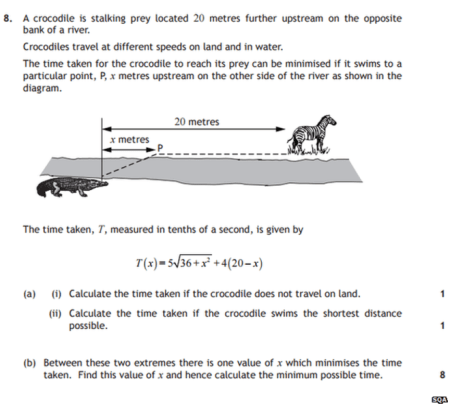

To illustrate the advice I’ve given I used this problem, which I leave as an exercise to the reader. It is a slightly amended version the first physics problem I was set as tutorial work when I began my undergraduate studies way back in 1982. I think it illustrates very well the points I have made above, and it doesn’t require any complicated mathematics – not even calculus! See how you get on…

Call me old-fashioned, but it doesn’t seem that difficult to me but I never took Scottish Highers and there have been many changes in Mathematics education since I did my O and A-levels; here’s the O-level Mathematics paper I took in 1979, for example. I wonder what my readers think? Comments through the box if you please.

Call me old-fashioned, but it doesn’t seem that difficult to me but I never took Scottish Highers and there have been many changes in Mathematics education since I did my O and A-levels; here’s the O-level Mathematics paper I took in 1979, for example. I wonder what my readers think? Comments through the box if you please.