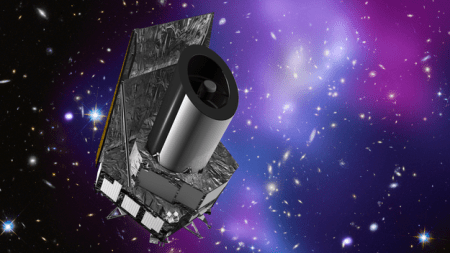

The Euclid spacecraft launched over a week ago so so here’s a short video explaining its trajectory and what it will do over the next weeks and months.

Archive for the The Universe and Stuff Category

Euclid Update

Posted in Euclid, The Universe and Stuff with tags ESA Euclid, Euclid, L2 on July 10, 2023 by telescoperBrainstorm Flash

Posted in Biographical, Euclid, Maynooth, The Universe and Stuff on July 6, 2023 by telescoperThe media activity surrounding the launch of Euclid on Saturday continues. Yesterday a piece by yours truly appeared on RTÉ Brainstorm with the title All you need to know about Euclid’s six year space mission. It subsequently got picked up by the main RTÉ News website on their News Lens panel, although it’s in second place after a story about a hot-dog eating competition:

P.S. There is also piece in siliconrepublic based on an interview with me here.

Opening the National Astronomy Meeting

Posted in Cardiff, Politics, The Universe and Stuff with tags Cardiff, Centre for Student Life, Mark Drakeford, National Astronomy Meeting 2023 on July 3, 2023 by telescoperMy first impressions of Cardiff after arriving yesterday is that a lot of things have changed. That sadly includes the fact that a number of my favourite places in the city centre have closed. On the other hand, some thing have improved. The Centre for Student Life, for example, is completely new since my days here and is a definite improvement on the previous dingy premises. It also just happens to be where the plenary sessions of the 2023 National Astronomy Meeting are being held:

The first plenary session of the week was opened by the First Minister of Wales, Mark Drakeford, who gave very a nice speech, in which he spoke very knowledgeably of the inspirational nature of astronomy as well as the history of the subject in Wales. It was a very impressive start to the week!

The Vice-chancellor of Cardiff University, Colin Riordan, was also there.

To Cardiff

Posted in Biographical, Cardiff, The Universe and Stuff on July 2, 2023 by telescoper

So I’m here in sunny Cardiff for the UK National Astronomy Meeting which is taking place here from tomorrow 3rd July until Friday 7th July. I’m here all week!

On my way here this morning, in Dublin Airport, I picked up a copy of the Sunday Times Ireland edition to find this:

It’s not a bad piece except I’m uncomfortable about being in the same subheading as Elon Musk! More amusingly still, my piece is next to a story about how your sex life needn’t stop when you reach 50. I wish someone had told me that 10 years ago!

Countdown to the Euclid Launch

Posted in Euclid, The Universe and Stuff with tags ESA Euclid, Euclid, Falcon-9, SpaceX on July 1, 2023 by telescoperToday’s the day! Weather permitting, of course, all eyes will be on Cape Canaveral for the launch of the Euclid satellite later this afternoon (as reckoned in Ireland). You can watch the launch on YouTube via the following stream (but it won’t start until 15.30 Irish Time; 16.30 CEST):

The Key Events to look for in local time are:

16:12 Euclid launch on SpaceX Falcon 9

16:53 Separation of Euclid from Falcon 9

16:57 Earliest expected time to establish communication with Euclid

After that, the mission is handed over to the ESA Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany as it sets out for the Sun-Earth Lagrange point L2. Approximately four weeks after launch, Euclid will enter in orbit around this point, which is located at 1.5 million km from Earth, in the opposite direction from the Sun. Once in orbit, mission operators will start verifying all the functions of the telescope. During this, residual water is outgassed, after which Euclid’s instruments will be turned on. Between one and three months after launch, Euclid will go through several calibrations and scientific performance tests and get ready for science. The telescope begins its early phase of the survey of the Universe three months after launch. There will be a preliminary release of a small amount of data in December 2024, but the first full data release – DR1 – will take about two years.

UPDATE: All critical stages of the launch passed satisfactorily, and contact has been established with the ground control. Euclid is now on its way to L2. Bon Voyage, Euclid!

Pushing Euclid

Posted in Biographical, Euclid, Science Politics, The Universe and Stuff with tags Euclid, Morning Ireland, NewsTalk, Sunday Times on June 30, 2023 by telescoperI’ve spent a sizeable chunk of the last two days answering press enquiries concerning the Euclid mission, due to be launch about 24 hours from now. Here is a picture of Euclid in the Falcon 9 fairing, getting ready to be moved to the launch facility. It’s all getting very real!

After talking with their researcher yesterday, this morning I did a short interview on Morning Ireland, which is on RTÉ Radio 1. It was shorter than I imagined because the previous item – about the ongoing ructions at RTÉ over various financial scandals – understandably overran quite a bit. The presenter, Rachel English, was very nice though and I think it went fairly well. I did another short interview on Newstalk Radio on a programme called Hard Shoulder, which took place at 5.48pm. I also spoke to a journalist from the Sunday Times Irish Edition, who I think will run a story on Sunday.

Anyway, the purpose of this media stuff is not to try to grab headlines – my involvement in Euclid is very small, really – but to generate some interest in the hope that Ireland takes a more active role in future space missions. I don’t know whether it will work, but I hope it does, and I feel obliged to try although it has made for a very busy day indeed!

NANOGrav Newsflash!

Posted in Astrohype, The Universe and Stuff with tags gravitational waves, Hellings-Downs, NANOGrav, SMBHs, stochastic gravitational wave background, supermassive black holes on June 29, 2023 by telescoperIn a post earlier this week I wrote that

There is a big announcement scheduled for Thursday by the NANOGrav collaboration. I don’t know what is on the agenda, but I suspect it may be the detection of a stochastic gravitational wave background using pulsar timing measurements. I may of course be quite wrong about that, but will blog about it anyway.

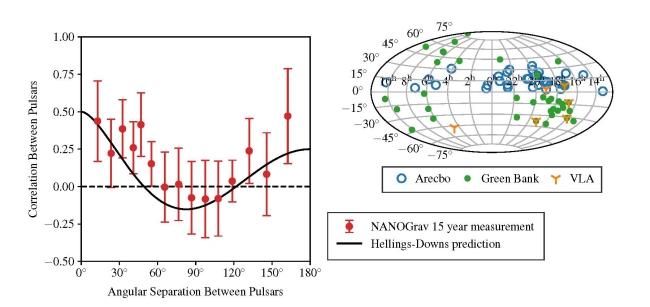

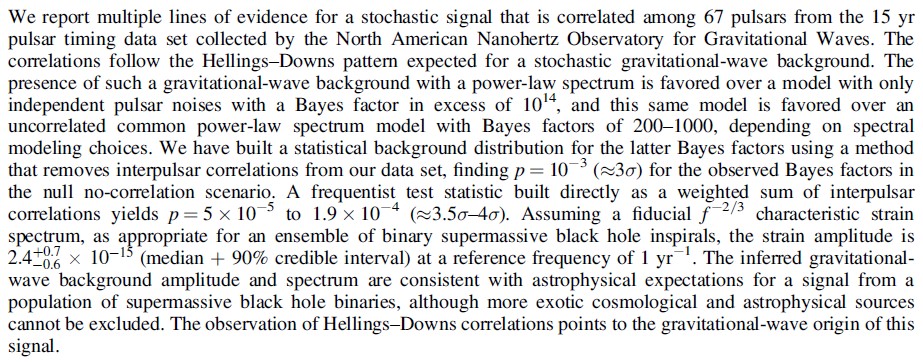

The press conference is not until 1pm EDT (6pm Irish Time) but the papers have already arrived and it appears I was correct in my inference. The papers can be found here, along with a summary. The main results paper is entitled The NANOGrav 15 yr Data Set: Evidence for a Gravitational-wave Background. Here is the abstract (click on the image to make it bigger):

In a nutshell, this evidence differs from the direct detection of gravitational waves by interferometric experiments, such as Advanced LIGO, in that it: (a) does not detect individual sources but an integrated background produced by many sources; (b) it is sensitive to much longer gravitational waves (measured in light-years rather than kilometres).; and (c) the statistical evidence of this detection is far less clear-cut.

While Advanced LIGO can – and does – detect gravitational waves from mergers of stellar mass black holes, the NANOGrav signal would correspond to similar events involving much more massive objects – supermassive black holes (SMBHs) – with masses exceeding a million times the mass of the Sun, such as the one found in the Galactic Centre. If this is the right interpretation, the signal will provide important information about how many such mergers are happening across the Universe and hence about the formation of such objects and their host galaxies.

SMBH mergers are not the only possible source of the NANOGrav signal, however, and you can bet your bottom dollar that there will now be an avalanche of theory papers on the arXiv purporting to explain the results in terms of more exotic models.

Incidentally, for a nice explanation of the Hellings-Downs correlation, see here. The figure from the paper is

I haven’t had time to go through the papers in detail so won’t comment on the results, at least partly because I find the presentation of the statistical results in the abstract a very confusing jumble of Bayesian and frequentist language which I find hard to penetrate. Hopefully it will make more sense when I have time to read the papers and/or when I watch the announcement later.

First Impression seeing the Euclid Telescope

Posted in Euclid, The Universe and Stuff with tags Cannes, EPO, Euclid, Thales on June 28, 2023 by telescoperWith just three days to go before the scheduled launch of the Euclid spacecraft on Saturday 1st July 2023, at 1612 Irish Time (GMT+1), the Education and Public Outreach (EPO) team have been continuing to ramp up its social media activity and the second YouTube video has now “dropped” (as you young people say).

This was filmed at Thales Alenia Space in Cannes, France, as members of the Euclid consortium from around the world gathered in anticipation to see the fully-assembled Euclid telescope for the first time as it underwent final tests before its journey to the launch site in Florida.

Two New Publications at the Open Journal of Astrophysics

Posted in OJAp Papers, Open Access, The Universe and Stuff with tags arXiv, arXiv:2301.04649, arXiv:2305.06347, Cosmology and NonGalactic Astrophysics on June 28, 2023 by telescoperTime to catch up with a couple of recent publications at the Open Journal of Astrophysics.

The first paper was published on Friday 23rd June. It is the 21st in Volume 6 (2023) and the 86th in all.

The primary classification for this paper is Cosmology and Nongalactic Astrophysics and its title is “CosmoPower-JAX: high-dimensional Bayesian inference with differentiable cosmological emulators”. The paper is about a new method, based on machine learning, to construct emulators for cosmological power spectra for the purpose of speeding up inference procedures. The software described in the paper is available here.

The authors are Davide Piras (of the University of Geneva, Switzerland) and Alessio Spurio Mancini (of the Mullard Space Sciences Laboratory, University College, London, UK)

Here is a screen grab of the overlay which includes the abstract:

You can click on the image of the overlay to make it larger should you wish to do so. You can find the officially accepted version of the paper on the arXiv here.

The second paper was published yesterday. It is the 22nd in Volume 6 (2023) and the 87th in all. Although 87 is an unlucky number for Australian cricketers – 13 short of a century – we’re still well on track to reach 100 papers by the end of the year.

Once again the primary classification for this paper is Cosmology and Nongalactic Astrophysics. The title of this one is “The alignment of galaxies at the Baryon Acoustic Oscillation scale” by Dennis van Dompseler, Christos Georgiou & Nora Elisa Chisari all of Utrecht University, in The Netherlands.

Here is a screen grab of the overlay which includes the abstract:

You can click on the image of the overlay to make it larger should you wish to do so. You can find the officially accepted version of the paper on the arXiv here.

Euclid’s “Red Book”

Posted in Euclid, The Universe and Stuff with tags arXiv:1110.3193, Euclid, Euclid Red Book on June 27, 2023 by telescoperWith the scheduled launch of ESA’s Euclid mission coming up this weekend, it is perhaps topical to share the document written almost 12 years ago that outlines the design concepts and describes the detailed scientific case. It’s a compendious piece, running to well over 100 pages but, as with virtually everything in astrophysics, the full Euclid Definition Study Report can be found on arXiv.

Here is the abstract:

Euclid is a space-based survey mission from the European Space Agency designed to understand the origin of the Universe’s accelerating expansion. It will use cosmological probes to investigate the nature of dark energy, dark matter and gravity by tracking their observational signatures on the geometry of the universe and on the cosmic history of structure formation. The mission is optimised for two independent primary cosmological probes: Weak gravitational Lensing (WL) and Baryonic Acoustic Oscillations (BAO). The Euclid payload consists of a 1.2 m Korsch telescope designed to provide a large field of view. It carries two instruments with a common field-of-view of ~0.54 deg2: the visual imager (VIS) and the near infrared instrument (NISP) which contains a slitless spectrometer and a three bands photometer. The Euclid wide survey will cover 15,000 deg2 of the extragalactic sky and is complemented by two 20 deg2 deep fields. For WL, Euclid measures the shapes of 30-40 resolved galaxies per arcmin2 in one broad visible R+I+Z band (550-920 nm). The photometric redshifts for these galaxies reach a precision of dz/(1+z) < 0.05. They are derived from three additional Euclid NIR bands (Y, J, H in the range 0.92-2.0 micron), complemented by ground based photometry in visible bands derived from public data or through engaged collaborations. The BAO are determined from a spectroscopic survey with a redshift accuracy dz/(1+z) =0.001. The slitless spectrometer, with spectral resolution ~250, predominantly detects Ha emission line galaxies. Euclid is a Medium Class mission of the ESA Cosmic Vision 2015-2025 programme, with a foreseen launch date in 2019. This report (also known as the Euclid Red Book) describes the outcome of the Phase A study.

arXiv:1110.3193

Euclid was formally adopted as an ESA M Class mission in June 2012. I’ve added the emphasis to the penultimate sentence to draw your attention to the fact that the launch of Euclid is about four years late.