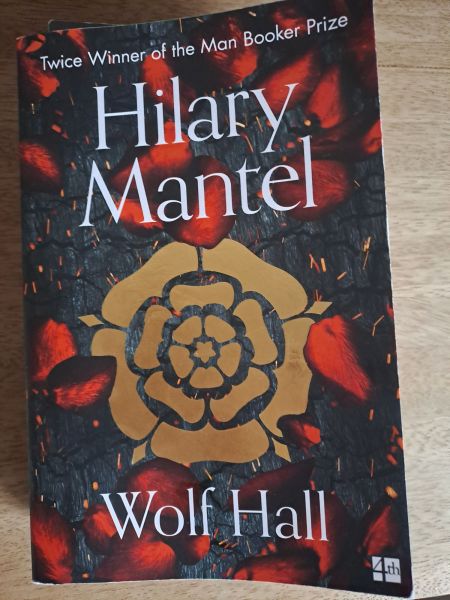

Still trying to use the spare time during my sabbatical to catch up on long-neglected reading, this Easter weekend – helped by the rainy weather – I finished Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel, the first of her novels that I’ve read. This “historical novel” won the Booker Prize in 2009 and I understand was made into a play and a TV series, neither of which I have seen.

The novel is set in Tudor England in the reign of Henry VIII and revolves around Thomas Cromwell, who rose from lowly beginnings in Putney to be one of the powerful men in the country. Cromwell gets a surprisingly sympathetic treatment, at odds with most of the historical record which treats him largely as a cruel and unscrupulous character, undoubtedly clever but given to threats and torture if appeals to reason failed. From a 21st century perspective, it’s hard to find redeeming features in Cromwell. Or anyone else in this story, to be honest.

The historical events of the period covered by the book are dominated by Henry’s attempts to have his marriage of 24 years to Catherine of Aragon annulled so he could marry Anne Boleyn, along the way having himself declared the Supreme Governor of the Church in England, causing a split with Rome. Henry does marry Anne, and she bears him a daughter, destined to become Elizabeth I, though her second pregnancy ends in a miscarriage. The book ends in 1535 just after the execution of Thomas More, beheaded for refusing to swear the Oath of Supremacy.

(More was portrayed sympathetically in the play and film A Man For All Seasons though he was much disposed to persecution of alleged heretics, many of whom he caused to be burned at the stake for such terrible crimes as distributing copies of the Bible printed in English. Significant chunks of the penultimate chapter are lifted from the script of A Man For All Seasons but given a very different spin.)

Henry VIII is also portrayed in a somewhat flattering light; Anne Boleyn rather less so. Mary Tudor, Henry’s eldest daughter by Catherine of Aragon, cuts an unsurprisingly forlorn and intransigent. There are also significant appearances from other figures familiar from schoolboy history: Hugh Latimer, Cardinal Wolsey, and Thomas Cranmer; as well as those whose story is not often told, such as Mary Boleyn (Anne’s older sister). I have a feeling that Hilary Mantel was being deliberately courting controversy with her heterodox approach to characterization. She probably succeeded, as many professional historians are on record as hating Wolf Hall as much of it is of questionable accuracy and some is outright fiction.

Incidentally, one of the most negative reactions to this book that I’ve seen is from Eamon Duffy who is on record as detesting the historical figure of Thomas Cromwell and was “mystified by his makeover in Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall from a thuggish ruthless commoner to a thoughtful sensitive figure”. I mention this particularly because Eamon Duffy, an ecclesiastical historian, was my tutor when I was an undergraduate at Magdalene College, Cambridge.

On the other hand, Wolf Hall not meant to be a work of scholarly history: it is a novel and I think you have to judge it by the standards of whether it succeeds as a work of fiction. I would say that it does. Although rather long-winded in places – it’s about 640 pages long – it is vividly written and does bring this period to life with colour and energy, and a great deal of humour, while not shying away from the brutality of the time; the execution scenes are unflinchingly gruesome. The book may not be accurate in terms of actual history, but it certainly creates a credible alternative vision of the time.

It’s interesting that the title of this book is Wolf Hall when that particular place – the seat of the Seymour family – hardly figures in the book. However, one character does make a few appearances, Jane Seymour, who just a year after the ending of this book would become the third wife of Henry VIII. It also happened that Thomas Cromwell’s son, Gregory, married Jane’s sister, Elizabeth. I suppose I will have to read the next book in the trilogy, Bring Up The Bodies, to hear Mantel’s version of those events…