I was (pleasantly) surprised to learn a few weeks ago that I shall be teaching particle physics again next academic year. That means that I’ll have to update to the notes to reflect the latest news from CERN. Researchers from the LHCb collaboration have published evidence for CP violation in baryons. The paper is published in Nature here.

For those of you not up with the lingo, CP is an operator that combines C (charge-conjugation, i.e. matter versus anti-matter) and P (parity, i.e. inversion of coordinates). Parity has been known since the 1950s to be violated in weak interactions, so the weak nuclear force distinguishes between states of odd and even parity. CP violation was first demonstrated in the 1960s CP in the decays of neutral kaons resulted in the Nobel Prize in 1980 for its discoverers Cronin and Fitch. CP violation has subsequeuntly been seen in many other meson decays.

But the mesons (consisting of a quark and an antiquark) are only half of the family of particles made from quarks; the others are the baryons which are made of three quarks (c.f. James Joyce’s “Three quarks for Muster Mark” in Finnegans Wake). Antibaryons consist of three antiquarks, but such are not mentioned in Finnegans Wake.

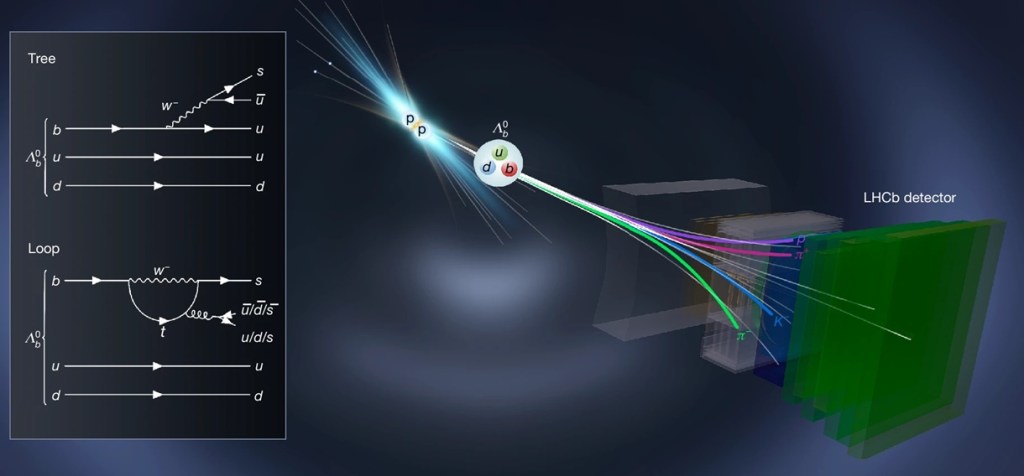

The baryons concerned in the LHCb experiment contain an up quark, a down quark and a beauty quark and were produced in proton–proton collisions at the Large Hadron Collider in 2011–2018. These baryons and antibaryons can decay via multiple channels. In one, a baryon decays to a proton, a positive K-meson and a pair of pions – or, conversely, an antibaryon decays to an antiproton, a negative K-meson and a pair of pions. CP violation should create an asymmetry between these processes, and the researchers found evidence of this asymmetry in the numbers of particles detected at different energies from all the collisions.

A problem with calculating the magnitude of this effect for baryons is that there is a contribution from the strong force – see the curly line indicating a gluon in the lower panel on the left above – and that is much harder to compute than a pure weak force (represented by the wavy lines indicating W– bosons. Yo will see that the tree and loop diagrams involve quark mixing, a process that allows quarks of different generations to couple via weak interactions; there is a buW vertex in the top panel and a tsW vertex in the bottom one. Given the uncertainties, it seems the results are consistent with the level of CP violation predicted in the Standard Model of particle physics.

The big question surrounding this result is whether it can account for the fact that our Universe – or at least our part of it -contains a preponderance of baryons over anti-baryons, so somehow the interactions going on during the Big Bang must have shown a preference for the former over the latter. This problem of baryogenesis is not explained in the Standard Model and, since these results are consistent with the Standard Model, the answer to that question is “no”…