Anyone who has studied theoretical physics for any time will be familiar with the simple harmonic oscillator, which I will call the SHO for short. This is a system that can be solved exactly and its solutions can be applied in a wide range of situations where it holds approximately, e.g. when looking at small oscillations around equilibrium. I’ve often remarked in lectures that we spend much of our lives solving the SHO problem in various guises, often pretending that the difficult system we have in front of us can, if looked at in the right way, and with sufficient optimism, be approximated by the much simpler SHO. Cue the old joke that if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like nail…

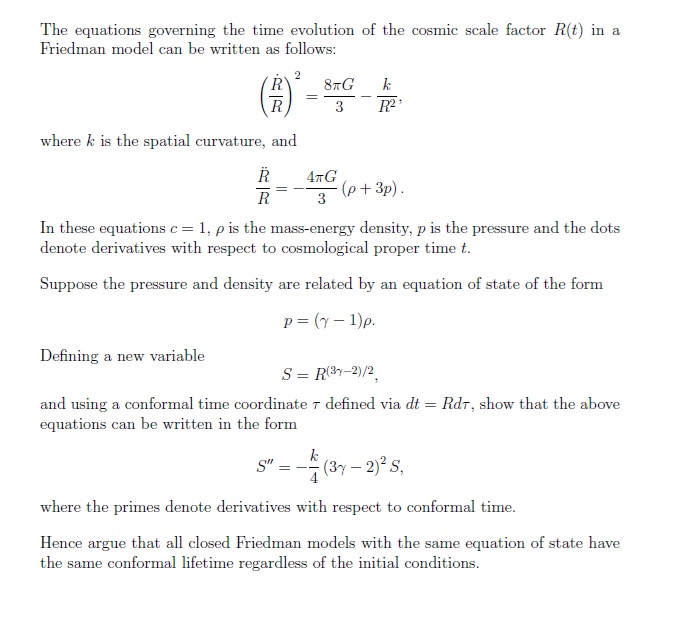

That rambling prelude occurred to me when I found this little problem in some old notes. It is a cute mathematical result that shows that the Friedman equations that underpin our standard cosmological model can in fact be written in the same form as those describing a Simple Harmonic Oscillator. In what follows we take the cosmological constant term to be zero.

The resulting equation is the SHO equation if k>0. I’m not sure whether this result is very useful for anything, but it is cute. It also goes to to show that, if looked at in the right way, the whole Universe is a Simple Harmonic Oscillator!