Since I’ve got my own computer again now I thought I’d celebrate by doing one of those rambling, inconsequential posts I haven’t had time to do recently.

Last week, in the run up to the European Championship semi-final between England and The Netherlands, I for some reason decided to look up what “The Netherlands” is in the Irish language. I did know this once, as it came up when I was trying to learn Irish a few years ago but I had forgotten. I remembered “England”, which is Sasana (cf. Saxon). Anyway, the answer is An Ísiltír. I’ll return to that in a moment.

Here are some other names:

Anyway, a couple of things may be interest. One is that you can see that most country names in Irish are introduced by An. This is the definite article in Irish; there is no indefinite article. This contrasts with English in which only a few names start with the definite article, “The Netherlands” being one. The exceptions in Irish include England (Sasana) and Scotland (Albain). Wales is An Bhreatain Bheag (literally “Little Britain”). Of relevance to the final of the European Championship, Spain is An Spáinn.

I should also mention that some nouns suffer an initial consonant mutation (in the form of lenition, i.e. softening) after the direct article. In modern Irish this is denoted by an h next to the initial consonant, hence Fhrainc, for example; the Irish word for “French” is Fraincis.

The second interesting thing pertains to An Ísiltír itself. The second part of this, tír, means “country” or “nation” – see the plural in the heading above – and the first, Ísil, means “low”. An Ísiltír is therefore literally “The Low Country”. I shared this fascinating insight on social media and found in the replies a mention that the Welsh name for The Netherlands is Yr Iseldiroedda meaning literally “The Low Lands”. The first part of this is clearly similar to the Irish, but the second is the plural of a different word meaning ground or earth or an area of land. There is a word tir in Welsh that means ground or earth or an area of land but it does not mean country or nation like the very similar Irish word; the word for that is gwlad. In Irish the word for land or ground or earth (or turf) is talamh.

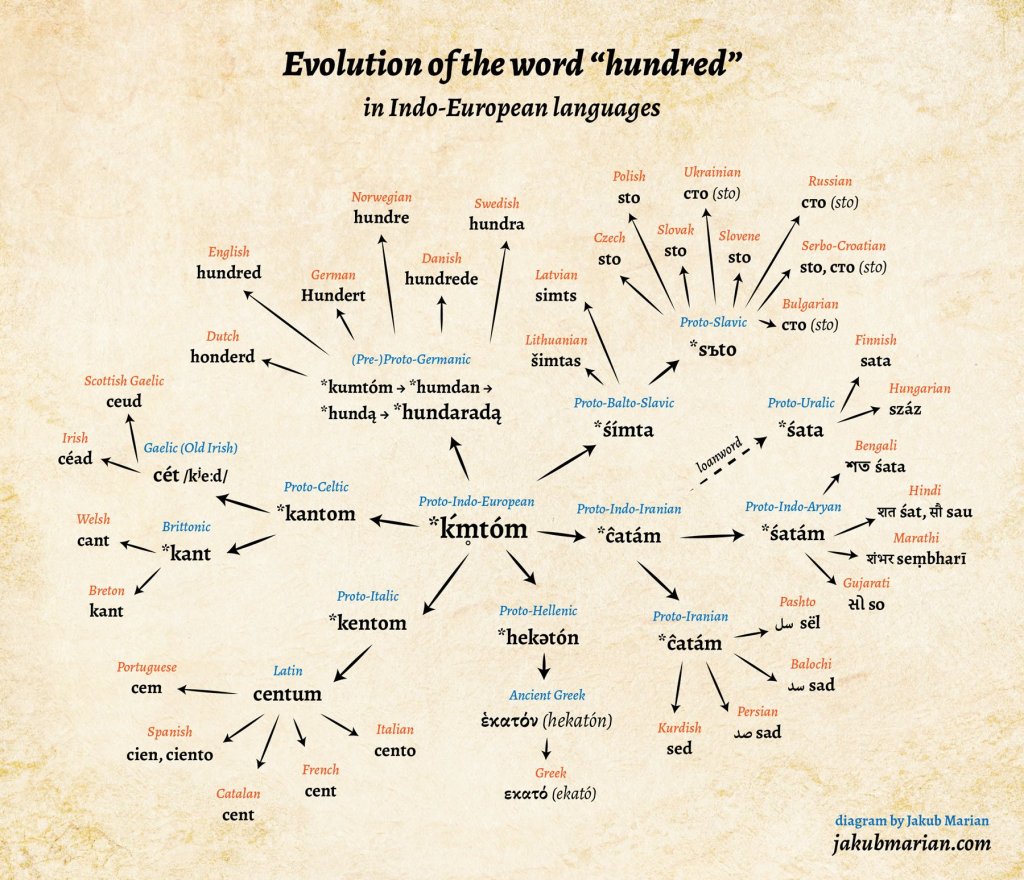

Welsh and Irish belong to distinct branches of the Celtic group of languages, the first wave of Indo-European languages to sweep across Europe. I blogged about this here. Celtic languages therefore share roots with many other Indo-European languages and very basic words in many branches of the tree often bear some similarity in form, if slight but significant differences in meaning. It seems that tír/tir illustrates this rather well. These two words also have a very similar form to the French terre which is derived from the Latin terra. And so I disappeared down an etymological rabbit hole and found that all these words are probably derived from a Proto-Indo-European word meaning “dry”, presumably through reference to “that which is dry” as opposed to the wet bits (although neither Ireland nor Wales is famous for being particular dry).

And to bring this little excursion back full circle, the Irish word tirim means “dry”…