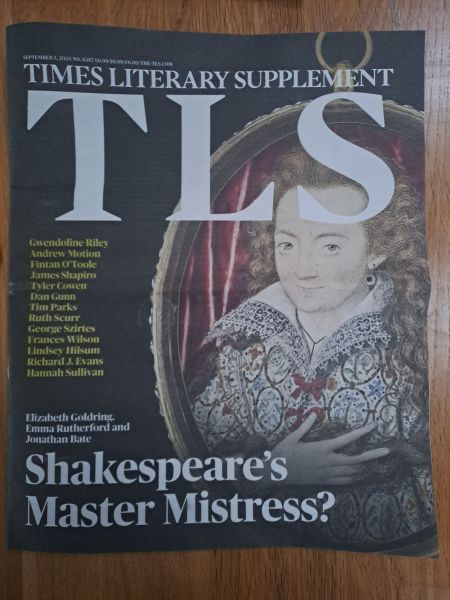

Today is National Poetry Day in the UK and Ireland but, instead of posting a poem like I usually do on this occasion, I thought I’d do a bit of reflecting on Shakespeare’s Sonnets. What prompted this is an article in the Times Literary Supplement I mentioned in a post on Monday. The cover picture shows a newly-discovered miniature by Nicholas Hilliard that is claimed to be of Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, and patron of William Shakespeare:

On the 20th May 1609, a collection of 154 Sonnets by William Shakespeare was published, which arguably represents at least as high a level of literary achievement as his plays. The “Master Mistress” in the title of the TLS article is a reference to Sonnet No. 20 in the collection, published on 20th May 1609, of 154 Sonnets by William Shakespeare, which arguably represents at least as high a level of literary achievement as his plays. Here is Sonnet No. 20 in the form usually printed nowadays:

A woman’s face with nature’s own hand painted,

Hast thou the master mistress of my passion,

A woman’s gentle heart but not acquainted

With shifting change as is false women’s fashion,

An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling:

Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth,

A man in hue all hues in his controlling,

Which steals men’s eyes and women’s souls amazeth.

And for a woman wert thou first created,

Till nature as she wrought thee fell a-doting,

And by addition me of thee defeated,

By adding one thing to my purpose nothing.

But since she pricked thee out for women’s pleasure,

Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure.

The somewhat androgynous facial appearance of Henry Wriothesley – seen in other portraits – has led some to suggest that the above Sonnet was addressed to him. Others think that the poem was addressed to a young male actor (a “boy player“) who played female roles on the stage, as was usual in Shakespeare’s time. It was illegal for women to perform on stage until 1660.

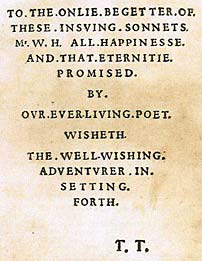

The dedication in the First Folio edition of the Sonnets, published in 1609, is shown on the left. The initials “T.T.” are accepted to stand for the name of the publisher Thomas Thorpe but the identity of “Mr. W.H.” is unknown. Of course “W.H.” is a reversal of the “H.W. ” that could be Henry Wriothesley, but would the publisher really use “Mr” to refer to a member of the nobility? Another curiosity is the prevalence of full stops, which is more characteristic of inscriptions carved in stone than on printed pages.

The First Folio edition was the only edition of the Sonnets published in Shakespeare’s lifetime and the circumstances of its publication remain uncertain to this day and not only because of identity of “Mr W.H.” For example, if it was authorised by Shakespeare, why did Shakespeare himself not write the dedication? Some have argued that it must have been published posthumously, so Shakespeare must have been dead in 1609, whereas most sources say he died in 1616.

Most of the poems (126 out of 154) contain poetic statements of love for a young man, often called the “Fair Youth”. However, there is also a group of sonnets addressed to the poet’s mistress, an anonymous “dark lady”, which are far much more sexual in content than those addressed to the “Fair Youth”. The usual interpretation of this is that the poet’s love for the boy was purely Platonic rather than sexual in nature. If Mr W.H. was a boy player then he would have been very young indeed, i.e. 13-17 years old…

Anyway, it was certainly a physical attraction: verse after verse speaks of the young man’s beauty. The first group of sonnets even encourage him to get married and have children so his beauty can continue and not die with his death. Sonnet 20 laments that the youth is not a woman, suggesting that this ruled out any sexual contact. These early poems seem to suggest a slightly distant relationship between the two as if they didn’t really know each other well. However, as the collection goes on the poems become more and more intimate and it’s hard for me to accept that there wasn’t some sort of involvement between the two. Although homosexual relationships were not officially tolerated in 17th Century England, they were not all that rare especially in the theatrical circles in which Shakespeare worked.

Oscar Wilde wrote a story called “A Portrait of Mr. W.H.” which suggests he is a young actor by the name of “Will Hughes”. The main evidence for this is Sonnet 20.

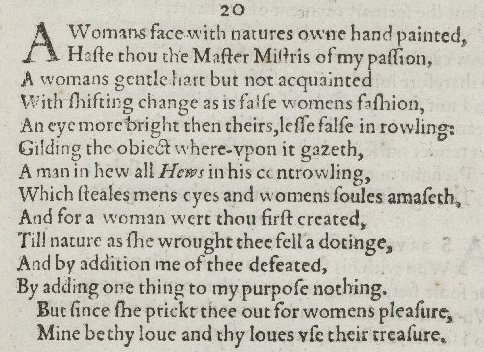

Look at the First Folio version:

The initial capital and emphasis of “Hews” seen in line 7 is very unusual and suggests that it is a joke (one of many in this poem), in the form of a pun on the preceding “hew”. It is suggested that “Hews” is actually “Hughes”. Ingenious, but I’m not convinced. There were many other meanings of “hew” in use in Shakespeare’s time; it was a variant spelling of “ewe” for example.

We’ll probably never know who Mr W.H. was – presumably not Smith – or indeed what was the real nature of his relationship to Shakespeare but we do not need to know that to read and enjoy the poems.

I do have a fundamental misgiving, though, about the assumption that the “Onlie begetter” of these sonnets means the person to whom they are addressed, or who inspired them. That assumption entirely disregards the “Dark Lady” sequence. There are at least two addressees so neither can be the only begetter, if that is what begetter is supposed to mean.

I think it more likely Mr W.H., whoever he was, is the person who caused the collection to be created and/or published, perhaps by sponsoring the First Folio. It’s also possible that these poems may have been commissioned over the years by Mr. W.H. and/or others – experts think they were written over a period of at least 16 years – and only published together at much later date. It is indeed said that some of verses were circulated in private well before they were published, though they may perhaps have been edited or otherwise tidied up for the 1609 edition. Perhaps Shakespeare supplemented his income by writing sonnets to order?

This line of thought also took me to another question: why does everyone assume that all 126 of the “Fair Youth” sonnets are about the same person? That person is never named and only occasionally described. Some of the 126 are thematically linked, but overall it is a collection rather than a sequence. Some are humorous and some are very serious indeed. Some are downright cryptic. I think it quite possible, especially if the poems really were written over a period of 16 years, that they not all addressed to the same individual. Once you accept the evident truth that there is more than one recipient, then why not more than two?

Some have taken this even further and asked: do we really know that all 154 sonnets were written by the same person? The same question is asked about Shakespeare’s work generally. Was there really one person behind his plays, or were they collaborative efforts.

Finally, I wonder for what purpose these sonnets were written. Were they actually sent to the addressee(s) as expressions of love, like letters, or were they private meditations, like one might write in a journal?

I don’t suppose we’ll ever really know the answers to these questions, but I find it fascinating that the origin of such a famous collection is enshrouded in so many mysteries! I promise to post more of them here in due course.