It’s been a while since I posed anything in the Bad Statistics file so I thought I’d return to the subject of one of my very first blog posts, although I’ll take a different tack this time and introduce it with different, though related, example.

The topic is forensic statistics, which has been involved in some high-profile cases and which demonstrates how careful probabilistic reasoning is needed to understand scientific evidence. A good example is the use of DNA profiling evidence. Typically, this involves the comparison of two samples: one from an unknown source (evidence, such as blood or semen, collected at the scene of a crime) and a known or reference sample, such as a blood or saliva sample from a suspect. If the DNA profiles obtained from the two samples are indistinguishable then they are said to “match” and this evidence can be used in court as indicating that the suspect was in fact the origin of the sample.

In courtroom dramas, DNA matches are usually presented as being very definitive. In fact, the strength of the evidence varies very widely depending on the circumstances. If the DNA profile of the suspect or evidence consists of a combination of traits that is very rare in the population at large then the evidence can be very strong that the suspect was the contributor. If the DNA profile is not so rare then it becomes more likely that both samples match simply by chance. This probabilistic aspect makes it very important to understand the logic of the argument very carefully.

So how does it all work? A DNA profile is not a complete map of the entire genetic code contained within the cells of an individual, which would be such an enormous amount of information that it would be impractical to use it in court. Instead, a profile consists of a few (perhaps half-a-dozen) pieces of this information called alleles. An allele is one of the possible codings of DNA of the same gene at a given position (or locus) on one of the chromosomes in a cell. A single gene may, for example, determine the colour of the blossom produced by a flower; more often genes act in concert with other genes to determine the physical properties of an organism. The overall physical appearance of an individual organism, i.e. any of its particular traits, is called the phenotype and it is controlled, at least to some extent, by the set of alleles that the individual possesses. In the simplest cases, however, a single gene controls a given attribute. The gene that controls the colour of a flower will have different versions: one might produce blue flowers, another red, and so on. These different versions of a given gene are called alleles.

Some organisms contain two copies of each gene; these are said to be diploid. These copies can either be both the same, in which case the organism is homozygous, or different in which case it is heterozygous; in the latter case it possesses two different alleles for the same gene. Phenotypes for a given allele may be either dominant or recessive (although not all are characterized in this way). For example, suppose the dominated and recessive alleles are called A and a, respectively. If a phenotype is dominant then the presence of one associated allele in the pair is sufficient for the associated trait to be displayed, i.e. AA, aA and Aa will both show the same phenotype. If it is recessive, both alleles must be of the type associated with that phenotype so only aa will lead to the corresponding traits being visible.

Now we get to the probabilistic aspect of this. Suppose we want to know what the frequency of an allele is in the population, which translates into the probability that it is selected when a random individual is extracted. The argument that is needed is essentially statistical. During reproduction, the offspring assemble their alleles from those of their parents. Suppose that the alleles for any given individual are chosen independently. If p is the frequency of the dominant gene and q is the frequency of the recessive one, then we can immediately write:

Using the product law for probabilities, and assuming independence, the probability of homozygous dominant pairing (i.e. AA) is p2, while that of the pairing aa is q2. The probability of the heterozygotic outcome is 2pq (the two possibilities, each of probability pq are Aa and aA). This leads to the result that

This called the Hardy-Weinberg law. It can easily be extended to cases where there are two or more alleles, but I won’t go through the details here.

Now what we have to do is examine the DNA of a particular individual and see how it compares with what is known about the population. Suppose we take one locus to start with, and the individual turns out to be homozygotic: the two alleles at that locus are the same. In the population at large the frequency of that allele might be, say, 0.6. The probability that this combination arises “by chance” is therefore 0.6 times 0.6, or 0.36. Now move to the next locus, where the individual profile has two different alleles. The frequency of one is 0.25 and that of the other is 0.75. so the probability of the combination is “2pq”, which is 0.375. The probability of a match at both these loci is therefore 0.36 times 0.375, or 13.5%. The addition of further loci gradually refines the profile, so the corresponding probability reduces.

This is a perfectly bona fide statistical argument, provided the assumptions made about population genetic are correct. Let us suppose that a profile of 7 loci – a typical number for the kind of profiling used in the courts – leads to a probability of one in ten thousand of a match for a “randomly selected” individual. Now suppose the profile of our suspect matches that of the sample left at the crime scene. This means that, either the suspect left the trace there, or an unlikely coincidence happened: that, by a 1:10,000 chance, our suspect just happened to match the evidence.

This kind of result is often quoted in the newspapers as meaning that there is only a 1 in 10,000 chance that someone other than the suspect contributed the sample or, in other words, that the odds against the suspect being innocent are ten thousand to one against. Such statements are gross misrepresentations of the logic, but they have become so commonplace that they have acquired their own name: the Prosecutor’s Fallacy.

To see why this is a fallacy, i.e. why it is wrong, imagine that whatever crime we are talking about took place in a big city with 1,000,000 inhabitants. How many people in this city would have DNA that matches the profile? Answer: about 1 in 10,000 of them ,which comes to 100. Our suspect is one. In the absence of any other information, the odds are therefore roughly 100:1 against him being guilty rather than 10,000:1 in favour. In realistic cases there will of course be additional evidence that excludes the other 99 potential suspects, so it is incorrect to claim that a DNA match actually provides evidence of innocence. This converse argument has been dubbed the Defence Fallacy, but nevertheless it shows that statements about probability need to be phrased very carefully if they are to be understood properly.

All this brings me to the tragedy that I blogged about in 2008. In 1999, Mrs Sally Clark was tried and convicted for the murder of her two sons Christopher, who died aged 10 weeks in 1996, and Harry who was only eight weeks old when he died in 1998. Sudden infant deaths are sadly not as uncommon as one might have hoped: about one in eight thousand families experience such a nightmare. But what was unusual in this case was that after the second death in Mrs Clark’s family, the distinguished paediatrician Sir Roy Meadows was asked by the police to investigate the circumstances surrounding both her losses. Based on his report, Sally Clark was put on trial for murder. Sir Roy was called as an expert witness. Largely because of his testimony, Mrs Clark was convicted and sentenced to prison.

After much campaigning, she was released by the Court of Appeal in 2003. She was innocent all along. On top of the loss of her sons, the courts had deprived her of her liberty for four years. Sally Clark died in 2007 from alcohol poisoning, after having apparently taken to the bottle after three years of wrongful imprisonment.The whole episode was a tragedy and a disgrace to the legal profession.

I am not going to imply that Sir Roy Meadows bears sole responsibility for this fiasco, because there were many difficulties in Mrs Clark’s trial. One of the main issues raised on Appeal was that the pathologist working with the prosecution had failed to disclose evidence that Harry was suffering from an infection at the time he died. Nevertheless, what Professor Meadows said on oath was so shockingly stupid that he fully deserves the vilification with which he was greeted after the trial. Two other women had also been imprisoned in similar circumstances, as a result of his intervention.

At the core of the prosecution’s case was a probabilistic argument that would have been torn to shreds had any competent statistician been called to the witness box. Sadly, the defence counsel seemed to believe it as much as the jury did, and it was never rebutted. Sir Roy stated, correctly, that the odds of a baby dying of sudden infant death syndrome (or “cot death”) in an affluent, non-smoking family like Sally Clarks, were about 8,543 to one against. He then presented the probability of this happening twice in a family as being this number squared, or 73 million to one against. In the minds of the jury this became the odds against Mrs Clark being innocent of a crime.

That this argument was not effectively challenged at the trial is truly staggering.

Remember that the product rule for combining probabilities

only reduces to

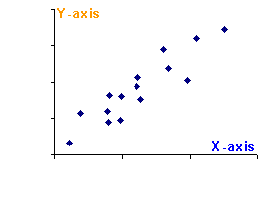

if the two events A and B are independent, i.e. that the occurrence of one event has no effect on the probability of the other. Nobody knows for sure what causes cot deaths, but there is every reason to believe that there might be inherited or environmental factors that might cause such deaths to be more frequent in some families than in others. In other words, sudden infant deaths might be correlated rather than independent. Furthermore, there is data about the frequency of multiple infant deaths in families. The conditional frequency of a second such event following an earlier one is not one in eight thousand or so, it’s just one in 77. This is hard evidence that should have been presented to the jury. It wasn’t.

Note that this testimony counts as doubly-bad statistics. It not only deploys the Prosecutor’s Fallacy, but applies it to what was an incorrect calculation in the first place!

Defending himself, Professor Meadows tried to explain that he hadn’t really understood the statistical argument he was presenting, but was merely repeating for the benefit of the court something he had read, which turned out to have been in a report that had not been even published at the time of the trial. He said

To me it was like I was quoting from a radiologist’s report or a piece of pathology. I was quoting the statistics, I wasn’t pretending to be a statistician.

I always thought that expert witnesses were suppose to testify about those things that they were experts about, rather than subjecting the jury second-hand flummery. Perhaps expert witnesses enjoy their status so much that they feel they can’t make mistakes about anything.

Subsequent to Mrs Clark’s release, Sir Roy Meadows was summoned to appear in front of a disciplinary tribunal at the General Medical Council. At the end of the hearing he was found guilty of serious professional misconduct, and struck off the medical register. Since he is retired anyway, this seems to me to be scant punishment. The judges and barristers who should have been alert to this miscarriage of justice have escaped censure altogether.

Although I am pleased that Professor Meadows has been disciplined in this fashion, I also hope that the General Medical Council does not think that hanging one individual out to dry will solve this problem. I addition, I think the politicians and legal system should look very hard at what went wrong in this case (and others of its type) to see how the probabilistic arguments that are essential in the days of forensic science can be properly incorporated in a rational system of justice. At the moment there is no agreed protocol for evaluating scientific evidence before it is presented to court. It is likely that such a body might have prevented the case of Mrs Clark from ever coming to trial. Scientists frequently seek the opinions of lawyers when they need to, but lawyers seem happy to handle scientific arguments themselves even when they don’t understand them at all.

I end with a quote from a press release produced by the Royal Statistical Society in the aftermath of this case:

Although many scientists have some familiarity with statistical methods, statistics remains a specialised area. The Society urges the Courts to ensure that statistical evidence is presented only by appropriately qualified statistical experts, as would be the case for any other form of expert evidence.

As far as I know, the criminal justice system has yet to implement such safeguards.

Galileo wasn’t as much of a mathematical genius as Newton, but he was highly imaginative, versatile and (very much unlike Newton) had an outgoing personality. He was also an able musician, fine artist and talented writer: in other words a true Renaissance man. His fame as a scientist largely depends on discoveries he made with the telescope. In particular, in 1610 he observed the four largest satellites of Jupiter, the phases of Venus and sunspots. He immediately leapt to the conclusion that not everything in the sky could be orbiting the Earth and openly promoted the Copernican view that the Sun was at the centre of the solar system with the planets orbiting around it. The Catholic Church was resistant to these ideas. He was hauled up in front of the Inquisition and placed under house arrest. He died in the year Newton was born (1642).

Galileo wasn’t as much of a mathematical genius as Newton, but he was highly imaginative, versatile and (very much unlike Newton) had an outgoing personality. He was also an able musician, fine artist and talented writer: in other words a true Renaissance man. His fame as a scientist largely depends on discoveries he made with the telescope. In particular, in 1610 he observed the four largest satellites of Jupiter, the phases of Venus and sunspots. He immediately leapt to the conclusion that not everything in the sky could be orbiting the Earth and openly promoted the Copernican view that the Sun was at the centre of the solar system with the planets orbiting around it. The Catholic Church was resistant to these ideas. He was hauled up in front of the Inquisition and placed under house arrest. He died in the year Newton was born (1642).

Karl Friedrich Gauss

Karl Friedrich Gauss  But the elder Jakob’s work on gambling clearly also had some effect on Daniel, as in 1735 the younger Bernoulli published an exceptionally clever study involving the application of probability theory to astronomy. It had been known for centuries that the orbits of the planets are confined to the same part in the sky as seen from Earth, a narrow band called the Zodiac. This is because the Earth and the planets orbit in approximately the same plane around the Sun. The Sun’s path in the sky as the Earth revolves also follows the Zodiac. We now know that the flattened shape of the Solar System holds clues to the processes by which it formed from a rotating cloud of cosmic debris that formed a disk from which the planets eventually condensed, but this idea was not well established in the time of Daniel Bernouilli. He set himself the challenge of figuring out what the chance was that the planets were orbiting in the same plane simply by chance, rather than because some physical processes confined them to the plane of a protoplanetary disk. His conclusion? The odds against the inclinations of the planetary orbits being aligned by chance were, well, astronomical.

But the elder Jakob’s work on gambling clearly also had some effect on Daniel, as in 1735 the younger Bernoulli published an exceptionally clever study involving the application of probability theory to astronomy. It had been known for centuries that the orbits of the planets are confined to the same part in the sky as seen from Earth, a narrow band called the Zodiac. This is because the Earth and the planets orbit in approximately the same plane around the Sun. The Sun’s path in the sky as the Earth revolves also follows the Zodiac. We now know that the flattened shape of the Solar System holds clues to the processes by which it formed from a rotating cloud of cosmic debris that formed a disk from which the planets eventually condensed, but this idea was not well established in the time of Daniel Bernouilli. He set himself the challenge of figuring out what the chance was that the planets were orbiting in the same plane simply by chance, rather than because some physical processes confined them to the plane of a protoplanetary disk. His conclusion? The odds against the inclinations of the planetary orbits being aligned by chance were, well, astronomical. It is impossible to overestimate the importance of the role played by

It is impossible to overestimate the importance of the role played by  A general proof of the Central Limit Theorem was finally furnished in 1838 by another astronomer,

A general proof of the Central Limit Theorem was finally furnished in 1838 by another astronomer,