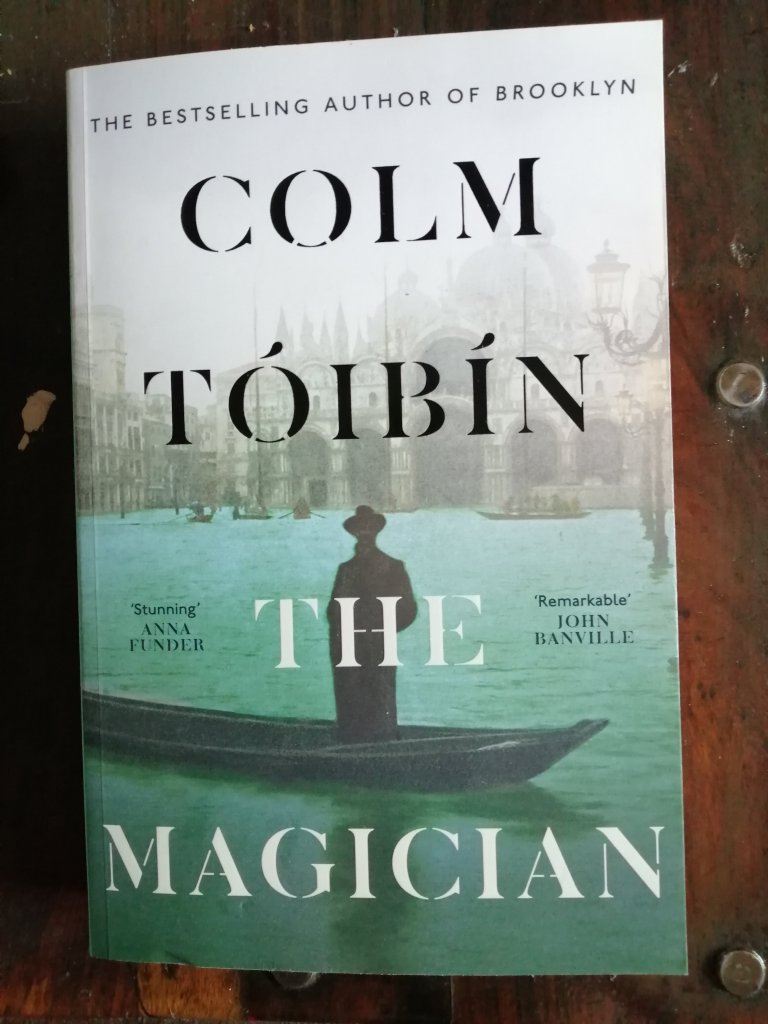

Continuing my attempt to catch up on a backlog of reading I have now finished The Magician by Colm Tóibín. A couple of years ago I attended a Zoom event featuring the author Colm Tóibín talking about this book, which is a fictionalised account of the life of Thomas Mann. It’s taken me a ridiculous long time to get round to it, but it was worth the wait.

The life of Thomas Mann was colourful, to say the least. Born in the German city of Lübeck in 1875, Mann’s father was a wealthy merchant and his mother was from Brazil. His elder brother Heinrich Mann was also a novelist essayist and playwright of considerable reputation. Despite his barely concealed homosexuality, Thomas Mann married Katia Pringsheim in 1905, his wife seemingly not minding about his sexual orientation. He led a comfortable life until he began to see the signs of the coming descent of Europe into the First World War. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929 and went into exile from Nazism in 1933, becoming an American citizen in 1944. In the post-War McCarthyite era he was made to feel less welcome in the USA for having visited East Germany and consequently under suspicion for communist sympathies. Not wanting to return to Germany, he spent most of the last years of his life in Zurich. He died in 1955 at the age of 80.

In some ways this work is reminiscent of The Dream of the Celt which I reviewed a few weeks ago, in that it’s a fictionalised biography, based partially on material found in diaries and with a theme of (partly) suppressed same-sex desire; several of his six offspring were gay or bisexual too. On the other hand I don’t think it’s accurate to think of this book so much as a biography of Thomas Mann but more of a biography of the late 19th and early 20th Century with Mann as the lens. In fact I finished the book without feeling that I knew very much at all about Thomas Mann’s character and personality. That’s probably deliberate as he seems to have cultivated an air of mystery surrounding himself. We follow Mann and his large family through the events leading up to both World Wars, and the effect these tumultuous times had on his siblings and offspring. His family endured more than its fair share of tragedy, with multiple suicides and other heartbreak.

An interesting aspect is the collection of little character sketches this book gives us of famous people with whom Mann interacted in his life. Mann was himself very famous indeed both in Europe and America. Tóibín gives us (not always flattering) views, through Mann’s eyes of, among many others: Gustav Mahler, Albert Einstein, Eleanor Roosevelt, Arnold Schoenberg, Christopher Isherwood and W.H. Auden. Incidentally, Auden married Mann’s daughter Erika so she could get British citizenship; the marriage was never consummated.

It’s a beautiful book, written in a style that frequently seems to mimic Mann’s own prose. Juxtaposing the ideas in his novels with the events happening when they were being written, both within his own family and in the wider world, provides fascinating insights. I have only read a couple of Thomas Mann’s books: Death in Venice and The Magic Mountain. Knowing more about his life, I now want to read these again and also read the others.

And so as one book disappears from my reading list, several more appear…

P.S. This is the novel in which the Mann family sits around listening to a gramophone record of In fernem Land sung by Leo Slezak I mentioned a few days ago.