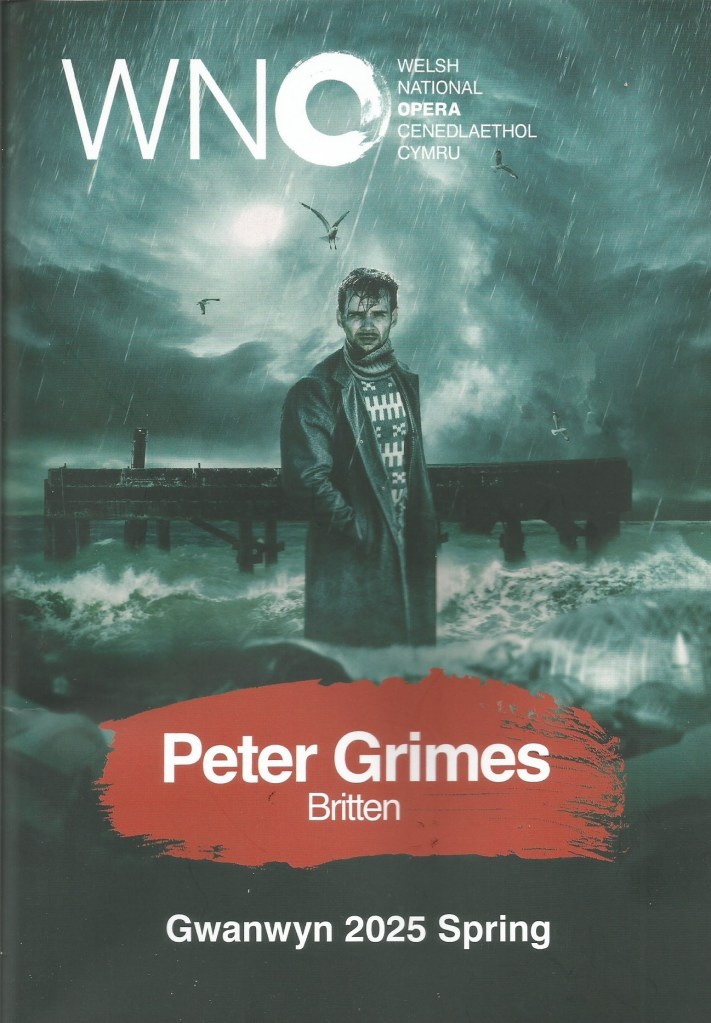

The reason for my flying visit to Cardiff this weekend was to visit the Wales Millennium Centre to catch the opening night of Welsh National Opera’s new production of the Opera Peter Grimes by Benjamin Britten. It was a full house and, being a premiere, there was a fair sprinkling of media types among the crowd. There will no doubt be many reviews but I don’t mind adding to the verbage. I’ve seen this Opera several times and it is one of my favourites in the entire repertoire.

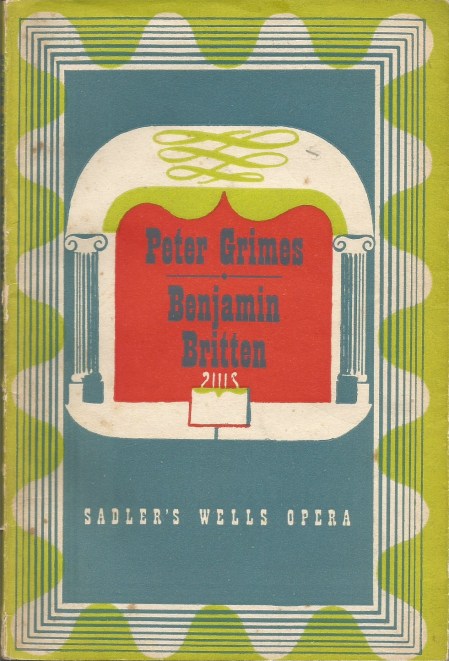

Peter Grimes premiered at Sadler’s Wells in London on 7th June 1945 almost 80 years ago. I wasn’t there – I’m not that old – but I do have an original programme from that season (left), bought in a second-hand bookshop. Perhaps surprisingly, given the grim subject matter and the intense music it was an immediate hit with audiences. Its popularity has not wained. Welsh National Opera gave its first performance in 1946, but is currently facing an uncertain future.

I’ve often heard Peter Grimes described as one of the greatest operas written in English. Well, as far as I’m concerned you can drop “written in English” from that sentence and it’s still true. I think it it’s a masterpiece, fit to rank alongside any by any composer. Searching through the back catalogue on this blog, however, I didn’t find any reviews of it, so the times I’ve seen it must have been before I started blogging back in 2008. I saw an excellent production by Opera North in Nottingham many moons ago, and also remember one at Covent Garden which stuck in my memory for its impressive staging.

Based on a character from the narrative poem The Borough by George Crabbe, the story revolves around the eponymous Peter Grimes, a fisherman, and the inhabitants of a small coastal village in Suffolk. Grimes is by no means a sympathetic character: he is an outcast with no social skills and is prone to fits of violent temper. The Opera begins witha Prologue in which Grimes is in court after the death of his apprentice; he is acquitted of any wrongdoing but the folk of the Borough – apart from the schoolteacher Ellen Orford and retired naval Captain Balstrode – still regard him as guilty. Against all advice, Grimes takes on another apprentice (John) whom he is subsequently suspected of mistreating. When the second boy dies (in accidental circumstances), Grimes flees with the crowd in pursuit. At the end he is given no choice but to take to his boat, sail it out to sea and sink it, taking his own life.

For me the key to the success of this Opera is its treatment of the character of Peter Grimes. In the original poem, Crabbe depicts Grimes is a monstrous figure rather like a pantomime villain. Britten is much more sympathetic: Grimes is misunderstood, a misft who as never been socialised; he just doesn’t know the rules that he should conform to. That’s his tragedy. Britten’s Grimes is not a villain. He’s not a hero either. At one point, shockingly, he even lashes out at Ellen Orford a lady who has shown him nothing but kindness. There’s good and bad in Grimes, like there is in all people. Who of us can say that we don’t share some of the faults of Peter Grimes? And if he’s bad what made him bad? Was he himself abused as a child? Could a little kindness along the way have made him better adjusted?

The Opera not just about Grimes, though. We get a vivid insight into the life of an isolated seaside community: the gossiping hypocrisy of the “good people” of the Borough, the debauchery of the landlady and her two “nieces” who cater to the needs of their male visitors, but above all the importance of the sea in their lives – stressed by Britten’s wonderful interludes describing dawn over the town, moonlight over the sea, and a raging storm. It also sheds light on the common practice of “buying” apprentices from the workhouse, essentially a means of slave labour, a systematic abuse far worse than anything Grimes ever does!

Anyway, to last night’s performance. In short, it was magnificent. The cast was very strong indeed: Nicky Spence shone in the role of Peter Grimes (tenor). Britten wrote the part to suit the characteristics of the voice of his partner, Peter Pears, and it doesn’t suit all tenor voices: the superb arioso When the Great Bear and Pleiades, for example, has dizzying head tones that challenges some singers. Ellen Orford was the excellent Sally Matthews (soprano) and Balstrode was the admirable baritone David Kempster.

I’ll mention three particularly memorable moments, near the end of the opera. The first is after the apprentice John has died; the gorgeous sea interlude Moonlight, which serves as a prelude to the third and final act, is played while the grieving Grimes cradles the lifeless corpse of the boy. The second is when Grimes is on the run, with the chorus calling his name and baying for blood. In fear of his life, he breaks down and is reduced to repeating his own name to himself. I’ve always found that scene unbearably moving and it was that way again last night. Finally, at the very end, the bodies of the two dead apprentices appear, one sprawled on a rock, the other standing eerily in the suspended boat which is tipped up vertically above the stage. When Grimes accepts Balstrode’s advice to drown himself, the two boys come to life; they exchange smiles, hold hands and walk off into the distance. It’s the only time Grimes looks happy in the whole performance. Only in death can he find his peace.

The staging is very spare but cleverly done. The basic set consists of a wet beach sloping up towards the rear above which from time to time a small fishing boat appears, suspended by wires, in a variety of attitudes. Otherwise there is little in the way of scenery. The clever part of this is the use of the dancers of Dance Ensemble Dawns. All the boys’ roles were in fact played by female dancers, including John the second apprentice, a non-speaking role played with great pathos by Maya Marsh whose use of body language was extraordinarily effective. Not only did they portray the boys of the village, often to be found generally misbehaving and taunting Peter Grimes, they also use their movements do evoke the storm in an extraordinarily compelling way. Not content with that they came on from time to time, in stylised fashion, to move scenery and props. The inn, for example, is conjured up by two simple props: a door frame and a window frame, held up by members of the ensemble for other members of the cast to walk or lean through. In all these contributions, the dancers were brilliant.

The simplicity of the staging probably reflects the financial crisis currently engulfing Welsh National Opera. They probably just didn’t have the money to pay for a elaborate sets, but it’s a testament to the skill and creativity of the designers that they were able to pull a triumph out of a financial disaster. I was sitting in the Circle so could see very well into the orchestra pit, where all the musicians of the Orchestra of Welsh National Opera were all wearing “SAVE OUR WNO” t-shirts. They played their hearts out. The WNO Chorus has always been excellent every time I’ve seen them, and last night was no exception.

At the end of the opera, the cast, chorus and dancers were joined on stage not only by the entire orchestra (including instruments, where possible) and many members of the technical team. I’ve never seen that happen before! There were speeches by the co-directors of WNO expressing their determination to carry on through the financial turbulence that threatens to drown them. Welsh National Opera is a wonderful part of the artistic and cultural scene not only in Wales but across the rest of the UK and beyond. It just cannot be allowed to wither.

P.S. Last night’s performance was recorded for later broadcast on BBC Radio 3.