I will just add a comment of my own. No job is worth risking your mental health for. Nor is anything else for that matter.

For further information see the Mental Health Awareness Week website.

Follow @telescoperI will just add a comment of my own. No job is worth risking your mental health for. Nor is anything else for that matter.

For further information see the Mental Health Awareness Week website.

Follow @telescoperI found the above map of the Tyne via the Tyne & Wear Archives on Twitter. It dates from the 1960s, and it caught my attention because it shows the area where I was born, between Walker and Wallsend.

I remember the Shipyards very well, especially the famous Neptune Yard of Swan Hunter. In the early 70s the huge ESSO Northumberland loomed above the terraced streets like a monster but now shipbuilding has all but vanished. So have most of the other industries lining the river, for that matter.

The other thing this map jogged my memory about was the Thermal Syndicate building. This was the site of a glassworks and the source of large quantities of silver sand, which my Dad used to buy and sell on to schools and playgroups as part of his educational supplies business, before it went under in the 1980s. The name always intrigued me as it made me imagine it was run by gangsters pushing winter underwear.

Follow @telescoperThree things led me to post this recording. One is that this piece (though not this performance) was one of the late Harry Kroto’s selections for Desert Island Discs. Another is that I had occasion to sort out my CD collection recently and I realised in doing so that I had more recordings of this Symphony than any other. And the third is that I heard a discussion on Radio 3 recently in which a record company executive noted that while sales of opera performances on DVD were very healthy, it was very difficult to sell DVDs of symphonic concerts. I am not particularly surprised by that but I have to say that I love the visual as well as the auditory experience of a classical concert. A large group of talented people coming together to make music is a great thing to watch, and it also helps understand the music a bit too. I’d much rather go to a live concert (even a mediocre one) than listen to a CD (even a very good one), but failing that I’d definitely go for a DVD.

All of this provides an excuse to show this film of the Vienna Philharmonic under the baton of Leonard Bernstein playing the gorgeous third moment (marked Ruhevoll) of Symphony No. 4 in G Major by Gustav Mahler. My favourite recording of this symphony is actually by Von Karajan with the Berlin Philharmonic on Deutsche Grammophon, but this is well worth watching to see the communication between Lenny and the band. And if you think Mahler is always gloomy and angst-ridden, hopefully this will make you change your mind.

Follow @telescoper

I saw an interesting news item this morning reporting that at one point last Sunday about 87% of Germany’s energy needs were supplied by renewable sources. The circumstances that led to this were relatively short-lived, but it is interesting nevertheless. I keep an eye on the UK’s national grid statistics from time to time and it rarely exceeds 20% in the form of renewables.

Anyway, all that reminded me of this, which appeared in the Guardian a couple of weeks weeks ago. It’s the last interview recorded by David Mackay before his untimely death from cancer in April. He’s characteristically direct in pointing out that the idea that the UK could be powered entirely by renewable energy is not at all practicable.

Follow @telescoper

In case you haven’t heard yet, news has just broken that Professor John Womersley (above), currently Chief Executive of the Science & Technology Facilities Council (STFC), has been appointed Director-General of the new European Spallation Source (ESS) in Lund, Sweden, and will therefore be stepping down from his post as Chief Executive of STFC in the autumn.

John has been Supreme Leader at STFC for five years now and, in my opinion, has done an excellent job in circumstances that have not always been easy. He will be a hard act to follow. I know he’s an occasional reader of this blog, so let me take this opportunity to wish him well in his new role.

Now, perhaps I should open a book on the likely contenders for the post of next Chief Executive of STFC?

Follow @telescoper

Once again the return of glorious weather heralds the return of the examination season at the University of Sussex, so here’s a lazy rehash of my previous offerings on the subject that I’ve posted around this time each year since I started blogging.

My feelings about examinations agree pretty much with those of William Wordsworth, who studied at the same University as me, as expressed in this quotation from The Prelude:

Of College labours, of the Lecturer’s room

All studded round, as thick as chairs could stand,

With loyal students, faithful to their books,

Half-and-half idlers, hardy recusants,

And honest dunces–of important days,

Examinations, when the man was weighed

As in a balance! of excessive hopes,

Tremblings withal and commendable fears,

Small jealousies, and triumphs good or bad–

Let others that know more speak as they know.

Such glory was but little sought by me,

And little won.

It seems to me a great a pity that our system of education – both at School and University – places such a great emphasis on examination and assessment to the detriment of real learning. On previous occasions, before I moved to the University of Sussex, I’ve bemoaned the role that modularisation has played in this process, especially in my own discipline of physics.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not opposed to modularisation in principle. I just think the way modules are used in many British universities fails to develop any understanding of the interconnection between different aspects of the subject. That’s an educational disaster because what is most exciting and compelling about physics is its essential unity. Splitting it into little boxes, taught on their own with no relationship to the other boxes, provides us with no scope to nurture the kind of lateral thinking that is key to the way physicists attempt to solve problems. The small size of many module makes the syllabus very “bitty” and fragmented. No sooner have you started to explore something at a proper level than the module is over. More advanced modules, following perhaps the following year, have to recap a large fraction of the earlier modules so there isn’t time to go as deep as one would like even over the whole curriculum.

In most UK universities (including Sussex), tudents take 120 “credits” in a year, split into two semesters. In many institutions, these are split into 10-credit modules with an examination at the end of each semester; there are two semesters per year. Laboratories, projects, and other continuously-assessed work do not involve a written examination, so the system means that a typical student will have 5 written examination papers in January and another 5 in May. Each paper is usually of two hours’ duration.

Such an arrangement means a heavy ratio of assessment to education, one that has risen sharply over the last decades, with the undeniable result that academic standards in physics have fallen across the sector. The system encourages students to think of modules as little bit-sized bits of education to be consumed and then forgotten. Instead of learning to rely on their brains to solve problems, students tend to approach learning by memorising chunks of their notes and regurgitating them in the exam. I find it very sad when students ask me what derivations they should memorize to prepare for examinations. A brain is so much more than a memory device. What we should be doing is giving students the confidence to think for themselves and use their intellect to its full potential rather than encouraging rote learning.

You can contrast this diet of examinations with the regime when I was an undergraduate. My entire degree result was based on six three-hour written examinations taken at the end of my final year, rather than something like 30 examinations taken over 3 years. Moreover, my finals were all in a three-day period. Morning and afternoon exams for three consecutive days is an ordeal I wouldn’t wish on anyone so I’m not saying the old days were better, but I do think we’ve gone far too far to the opposite extreme. The one good thing about the system I went through was that there was no possibility of passing examinations on memory alone. Since they were so close together there was no way of mugging up anything in between them. I only got through by figuring things out in the exam room.

I think the system we have here at the University of Sussex is much better than I’ve experienced elsewhere. For a start the basic module size is 15 credits. This means that students are usually only doing four things in parallel, and they consequently have fewer examinations, especially since they also take laboratory classes and other modules which don’t have a set examination at the end. There’s also a sizeable continuously assessed component (30%) for most modules so it doesn’t all rest on one paper. Although in my view there’s still too much emphasis on assessment and too little on the joy of finding things out, it’s much less pronounced than elsewhere. Maybe that’s one of the reasons why the Department of Physics & Astronomy does so consistently well in the National Student Survey?

We also have modules called Skills in Physics which focus on developing the problem-solving skills I mentioned above; these are taught through a mixture of lectures and small-group tutorials. I don’t know what the students think of these sessions, but I always enjoy them because the problems set for each session are generally a bit wacky, some of them being very testing. In fact I’d say that I’m very impressed at the technical level of the modules in the Department of Physics & Astronomy generally. I’ve been teaching Green’s Functions, Conformal Transformations and the Calculus of Variations to second-year students this semester. Those topics weren’t on the syllabus at all in my previous institution!

Anyway, my Theoretical Physics paper is next week (on 19th May) so I’ll find out if the students managed to learn anything despite having such a lousy lecturer. Which reminds me, I must remember to post some worked examples online to help them with their revision.

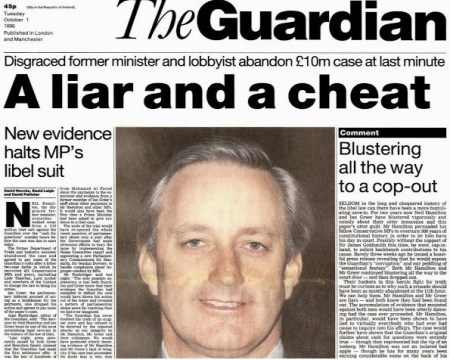

Follow @telescoperLast week’s elections to the Welsh Assembly saw the UK Independence Party winning seats in the Senedd for the very first time, although Welsh Labour remained the largest party by a comfortable margin despite losing a seat to Plaid Cymru. Among the 7 UK AMs elected was disgraced former Conservative MP Neil Hamilton who featured in this Guardian headline just 20 years ago.

Following this “Cash for Questions” scandal, he lost his seat in the 1997 General Election, at which point he left politics and joined UKIP.

Not content with merely winning a seat in the Assembly elections, Mr Hamilton then ousted former leader Nathan Gill of UKIP Wales and is now running the show. It’s been a bizarre turn of events. There’s clearly no end to his ambition (nor any beginning to his integrity).

Questions may be asked about a person such as Neil Hamilton could have been voted into power, but it’s not year clear how much it will cost to ask them.

All I can say is I hope they keep a close eye on the cutlery in the Senedd canteen.

Follow @telescoper

Interesting comments on referendums authored by academics from the University of Sussex, although it seems to me that the thing that most affects the outcome of a referendum is how many people vote on each side…

Kai Oppermann and Paul Taggart

Donald Rumsfeld famously talked about ‘known knowns’ and ‘known unknowns’. Looking systematically at referendums and at the experience of these in Europe, we can learn from what has happened in other European referendums to help us in looking at what may happen in the UK’s referendum on EU membership. There may be uncertainty ahead but we can know what we don’t know from previous experience. We suggest that there are six lessons we can learn

The one ‘known known’ we have is the state of the polls at the outset. But early in the campaign, opinion polls tell us very little about what the outcome of the referendum will be on 23 June. Around 20% of voters are still undecided. More than that, voting behaviour in referendums is much less settled and more fluid than in general elections. This…

View original post 1,298 more words

Today provided me with a (sadly rare) opportunity to join in our weekly Cosmology Journal Club at the University of Sussex. I don’t often get to go because of meetings and other commitments. Anyway, one of the papers we looked at (by Clerkin et al.) was entitled Testing the Lognormality of the Galaxy Distribution and weak lensing convergence distributions from Dark Energy Survey maps. This provides yet more examples of the unreasonable effectiveness of the lognormal distribution in cosmology. Here’s one of the diagrams, just to illustrate the point:

The points here are from MICE simulations. Not simulations of mice, of course, but simulations of MICE (Marenostrum Institut de Ciencies de l’Espai). Note how well the curves from a simple lognormal model fit the calculations that need a supercomputer to perform them!

The points here are from MICE simulations. Not simulations of mice, of course, but simulations of MICE (Marenostrum Institut de Ciencies de l’Espai). Note how well the curves from a simple lognormal model fit the calculations that need a supercomputer to perform them!

The lognormal model used in the paper is basically the same as the one I developed in 1990 with Bernard Jones in what has turned out to be my most-cited paper. In fact the whole project was conceived, work done, written up and submitted in the space of a couple of months during a lovely visit to the fine city of Copenhagen. I’ve never been very good at grabbing citations – I’m more likely to fall off bandwagons rather than jump onto them – but this little paper seems to keep getting citations. It hasn’t got that many by the standards of some papers, but it’s carried on being referred to for almost twenty years, which I’m quite proud of; you can see the citations-per-year statistics even seen to be have increased recently. The model we proposed turned out to be extremely useful in a range of situations, which I suppose accounts for the citation longevity:

Citations die away for most papers, but this one is actually attracting more interest as time goes on! I don’t think this is my best paper, but it’s definitely the one I had most fun working on. I remember we had the idea of doing something with lognormal distributions over coffee one day, and just a few weeks later the paper was finished. In some ways it’s the most simple-minded paper I’ve ever written – and that’s up against some pretty stiff competition – but there you go.

Citations die away for most papers, but this one is actually attracting more interest as time goes on! I don’t think this is my best paper, but it’s definitely the one I had most fun working on. I remember we had the idea of doing something with lognormal distributions over coffee one day, and just a few weeks later the paper was finished. In some ways it’s the most simple-minded paper I’ve ever written – and that’s up against some pretty stiff competition – but there you go.

The lognormal seemed an interesting idea to explore because it applies to non-linear processes in much the same way as the normal distribution does to linear ones. What I mean is that if you have a quantity Y which is the sum of n independent effects, Y=X1+X2+…+Xn, then the distribution of Y tends to be normal by virtue of the Central Limit Theorem regardless of what the distribution of the Xi is If, however, the process is multiplicative so Y=X1×X2×…×Xn then since log Y = log X1 + log X2 + …+log Xn then the Central Limit Theorem tends to make log Y normal, which is what the lognormal distribution means.

The lognormal is a good distribution for things produced by multiplicative processes, such as hierarchical fragmentation or coagulation processes: the distribution of sizes of the pebbles on Brighton beach is quite a good example. It also crops up quite often in the theory of turbulence.

I’ll mention one other thing about this distribution, just because it’s fun. The lognormal distribution is an example of a distribution that’s not completely determined by knowledge of its moments. Most people assume that if you know all the moments of a distribution then that has to specify the distribution uniquely, but it ain’t necessarily so.

If you’re wondering why I mentioned citations, it’s because they’re playing an increasing role in attempts to measure the quality of research done in UK universities. Citations definitely contain some information, but interpreting them isn’t at all straightforward. Different disciplines have hugely different citation rates, for one thing. Should one count self-citations?. Also how do you apportion citations to multi-author papers? Suppose a paper with a thousand citations has 25 authors. Does each of them get the thousand citations, or should each get 1000/25? Or, put it another way, how does a single-author paper with 100 citations compare to a 50 author paper with 101?

Or perhaps a better metric would be the logarithm of the number of citations?

Follow @telescoperThe other day I came across something I’ve never seen before: an academic paper about cryptic crosswords. It’s in an open access journal so feel free to clock – it’s not behind a paywall. Anyway, the abstract reads:

This paper presents a relatively unexplored area of expertise research which focuses on the solving of British-style cryptic crossword puzzles. Unlike its American “straight-definition” counterparts, which are primarily semantically-cued retrieval tasks, the British cryptic crossword is an exercise in code-cracking detection work. Solvers learn to ignore the superficial “surface reading” of the clue, which is phrased to be deliberately misleading, and look instead for a grammatical set of coded instructions which, if executed precisely, will lead to the correct (and only) answer. Sample clues are set out to illustrate the task requirements and demands. Hypothesized aptitudes for the field might include high fluid intelligence, skill at quasi-algebraic puzzles, pattern matching, visuospatial manipulation, divergent thinking and breaking frame abilities. These skills are additional to the crystallized knowledge and word-retrieval demands which are also a feature of American crossword puzzles. The authors present results from an exploratory survey intended to identify the characteristics of the cryptic crossword solving population, and outline the impact of these results on the direction of their subsequent research. Survey results were strongly supportive of a number of hypothesized skill-sets and guided the selection of appropriate test content and research paradigms which formed the basis of an extensive research program to be reported elsewhere. The paper concludes by arguing the case for a more grounded approach to expertise studies, termed the Grounded Expertise Components Approach. In this, the design and scope of the empirical program flows from a detailed and objectively-based characterization of the research population at the very onset of the program.

I still spend quite a lot of my spare time solving these “British-style” cryptic crossword puzzles. In fact I simply can’t put a crossword down until I’ve solved all the clues, behaviour which I admit is bordering on the pathological. Still, I think of it as a kind of mental jogging, forcing your brain to work in unaccustomed ways is probably good to develop mental fitness for other more useful things. I won’t claim to have a “high fluid intelligence” or any other of the attributes described in the abstract, however. As a matter of fact I think in many ways cryptic crosswords are easier than the straight “American-style” definition puzzle. I’ll explain why shortly. I can’t remember when I first started doing cyptic crossword puzzles, or even how I learned to do them. But then people can learn languages simply by picking them up as they go along so that’s probably how I learned to do crosswords. Most people I know who don’t do cryptic crosswords tend to think of them like some sort of occult practice, although I’ve never actually been thrown off a plane for doing one!

If you’ve never done one of these puzzles before, you probably won’t understand the clues at all even if you know the answer and I can’t possibly explain them in a single post. In a nutshell, however, they involve clues that usually give two routes to the word to be entered in the crossword grid. One is a definition of the solution word and the other is a subsidiary cryptic allusion to it. Usually the main problem to be solved involves the identification of the primary definition and secondary cryptic part, which are usually heavily disguised. The reason why I think cryptic puzzles are in some ways easier than the “straight-definition” variety is that they provide two different routes to the solution rather than one definition. The difficulty is just learning to parse the clue and decide what each component means.

The secondary clue can be of many different types. The most straightforward just exploits multiple meanings. For example, take

Fleeces, things often ordered by men of rank [6]

The answer to this is RIFLES which is defined by “fleeces” in one sense, but “men of rank” (soldiers) also order their arms hence giving a different meaning. Other types include puns, riddles, anagrams, hidden words, and so on. Many of these involve an operative word or phrase instructing the solver to do something with the letters in the clue, e.g.

Port’s apt to make you steer it erratically [7]

has the solution TRIESTE, which is an anagram of STEER+IT, port being the definition.

Most compilers agree however that the very best type of clue is of the style known as “&lit” (short for “and literally what it says”). Such clues are very difficult to construct and are really beautiful when they work because both the definition and cryptic parts comprise the same words read in different ways. Here’s a simple example

The ultimate of turpitide in Lent [5]

which is FEAST. Here we have “e” as the last letter of turpitude in “fast” (lent) giving “feast” but a feast is exactly what the clue says too. Nice.

Some clues involve more than one element of this type and some defy further explanation altogether, but I hope this at least gives you a clue as to what is involved.

Cryptic crosswords like the ones you find in British newspapers were definitely invented in the United Kingdom, although the crossword itself was probably born in the USA. The first great compiler of the cryptic type used the pseudonym Torquemada in the Observer. During the 1930s such puzzles became increasingly popular with many newspapers, including famously The Times, developing their own distinctive style. People tend to assume that The Times crossword is the most difficult, but I’m not sure. I don’t actually buy that paper but whenever I’ve found one lying around I’ve never found the crossword particularly hard or, more importantly, particularly interesting.

With the demise of the Independent, source of many prize dictionaries, I have now returned to the Guardian and Observer puzzles at the weekend as well as the interesting mixture of cryptic and literary clues of the puzzle in the weekly Times Literary Supplement and the “Genius” puzzle in The Oldie. I’ve won both of these a few times, actually, including the TLS prize just last week (£40 cash).

I also like to do the bi-weekly crossword set by Cyclops in Private Eye which has clues which are not only clever but also laced with a liberal helping of lavatorial humour and topical commentary which is right up my street. Many of the answers (“lights” in crossword parlance) are quite rude, such as

Local energy source of stress for Bush [5]

which is PUBES (“pub” from “local”+ E for energy +S for “source of stress”; Bush is the definition).

I send off the answers to the Eye crossword every time but have never won it yet. That one has a cash prize of £100.

Anyway, Torquemada, who I mentioned above, was eventually followed as the Observer’s crossword compiler by the great Ximenes (real name D.S. Macnutt) who wrote a brilliant book called the Art of the Crossword which I heartily recommend if you want to learn more about the subject. One of the nice stories in his book concerns the fact that crossword puzzles of the cryptic type were actually used to select recruits for British Intelligence during the Second World War, but this had a flip side. In late May 1944 the chief crossword setter for the Daily Telegraph was paid a visit by some heavies from MI5. It turned out that in a recent puzzle he had used the words MULBERRY, PLUTO, NEPTUNE and OVERLORD all of which were highly confidential code words to be used for the forthcoming D-Day invasion. The full background to this curious story is given here.

Follow @telescoper