Nature News has reported on what appears to be the paper with the longest author list on record. This article has so many authors – 5,154 altogether – that 24 pages (out of a total of 33 in the paper) are devoted just to listing them, and only 9 to the actual science. Not, surprisingly the field concerned is experimental particle physics and the paper emanates from the Large Hadron Collider; it involves combining data from the CMS and ATLAS detectors to estimate the mass of the Higgs Boson. In my own fields of astronomy and cosmology, large consortia such as the Planck collaboration are becoming the rule rather than exception for observational work. Large ollaborations have achieved great things not only in physics and astronomy but also in other fields. A for paper in genomics with over a thousand authors has recently been published and the trend for ever-increasing size of collaboration seems set to continue.

I’ve got nothing at all against large collaborative projects. Quite the opposite, in fact. They’re enormously valuable not only because frontier research can often only be done that way, but also because of the wider message they send out about the benefits of international cooperation.

Having said that, one thing these large collaborations do is expose the absurdity of the current system of scientific publishing. The existence of a paper with 5000 authors is a reductio ad absurdum proof that the system is broken. Papers simply do not have 5000 “authors”. In fact, I would bet that no more than a handful of the “authors” listed on the record-breaking paper have even read the article, never mind written any of it. Despite this, scientists continue insisting that constributions to scientific research can only be measured by co-authorship of a paper. The LHC collaboration that kicked off this piece includes all kinds of scientists: technicians, engineers, physicists, programmers at all kinds of levels, from PhD students to full Professors. Why should we insist that the huge range of contributions can only be recognized by shoe-horning the individuals concerned into the author list? The idea of a 100-author paper is palpably absurd, never mind one with fifty times that number.

So how can we assign credit to individuals who belong to large teams of researchers working in collaboration?

For the time being let us assume that we are stuck with authorship as the means of indicating a contribution to the project. Significant issues then arise about how to apportion credit in bibliometric analyses, e.g. through citations. Here is an example of one of the difficulties: (i) if paper A is cited 100 times and has 100 authors should each author get the same credit? and (ii) if paper B is also cited 100 times but only has one author, should this author get the same credit as each of the authors of paper A?

An interesting suggestion over on the e-astronomer a while ago addressed the first question by suggesting that authors be assigned weights depending on their position in the author list. If there are N authors the lead author gets weight N, the next N-1, and so on to the last author who gets a weight 1. If there are 4 authors, the lead gets 4 times as much weight as the last one.

This proposal has some merit but it does not take account of the possibility that the author list is merely alphabetical which actually was the case in all the Planck publications, for example. Still, it’s less draconian than another suggestion I have heard which is that the first author gets all the credit and the rest get nothing. At the other extreme there’s the suggestion of using normalized citations, i.e. just dividing the citations equally among the authors and giving them a fraction 1/N each. I think I prefer this last one, in fact, as it seems more democratic and also more rational. I don’t have many publications with large numbers of authors so it doesn’t make that much difference to me which you measure happen to pick. I come out as mediocre on all of them.

No suggestion is ever going to be perfect, however, because the attempt to compress all information about the different contributions and roles within a large collaboration into a single number, which clearly can’t be done algorithmically. For example, the way things work in astronomy is that instrument builders – essential to all observational work and all work based on analysing observations – usually get appended onto the author lists even if they play no role in analysing the final data. This is one of the reasons the resulting papers have such long author lists and why the bibliometric issues are so complex in the first place.

Having thousands of authors who didn’t write a single word of the paper seems absurd, but it’s the only way our current system can acknowledge the contributions made by instrumentalists, technical assistants and all the rest. Without doing this, what can such people have on their CV that shows the value of the work they have done?

What is really needed is a system of credits more like that used in the television or film. Writer credits are assigned quite separately from those given to the “director” (of the project, who may or may not have written the final papers), as are those to the people who got the funding together and helped with the logistics (production credits). Sundry smaller but still vital technical roles could also be credited, such as special effects (i.e. simulations) or lighting (photometic calibration). There might even be a best boy. Many theoretical papers would be classified as “shorts” so they would often be written and directed by one person and with no technical credits.

The point I’m trying to make is that we seem to want to use citations to measure everything all at once but often we want different things. If you want to use citations to judge the suitability of an applicant for a position as a research leader you want someone with lots of directorial credits. If you want a good postdoc you want someone with a proven track-record of technical credits. But I don’t think it makes sense to appoint a research leader on the grounds that they reduced the data for umpteen large surveys. Imagine what would happen if you made someone director of a Hollywood blockbuster on the grounds that they had made the crew’s tea for over a hundred other films.

Another question I’d like to raise is one that has been bothering me for some time. When did it happen that everyone participating in an observational programme expected to be an author of a paper? It certainly hasn’t always been like that.

For example, go back about 90 years to one of the most famous astronomical studies of all time, Eddington‘s measurement of the bending of light by the gravitational field of the Sun. The paper that came out from this was this one

A Determination of the Deflection of Light by the Sun’s Gravitational Field, from Observations made at the Total Eclipse of May 29, 1919.

Sir F.W. Dyson, F.R.S, Astronomer Royal, Prof. A.S. Eddington, F.R.S., and Mr C. Davidson.

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series A., Volume 220, pp. 291-333, 1920.

This particular result didn’t involve a collaboration on the same scale as many of today’s but it did entail two expeditions (one to Sobral, in Brazil, and another to the Island of Principe, off the West African coast). Over a dozen people took part in the planning, in the preparation of of calibration plates, taking the eclipse measurements themselves, and so on. And that’s not counting all the people who helped locally in Sobral and Principe.

But notice that the final paper – one of the most important scientific papers of all time – has only 3 authors: Dyson did a great deal of background work getting the funds and organizing the show, but didn’t go on either expedition; Eddington led the Principe expedition and was central to much of the analysis; Davidson was one of the observers at Sobral. Andrew Crommelin, something of an eclipse expert who played a big part in the Sobral measurements received no credit and neither did Eddington’s main assistant at Principe.

I don’t know if there was a lot of conflict behind the scenes at arriving at this authorship policy but, as far as I know, it was normal policy at the time to do things this way. It’s an interesting socio-historical question why and when it changed.

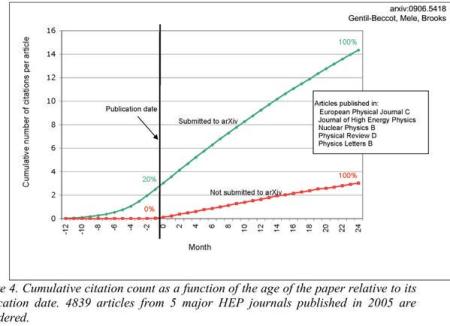

I’ve rambled off a bit so I’ll return to the point that I was trying to get to, which is that in my view the real problem is not so much the question of authorship but the idea of the paper itself. It seems quite clear to me that the academic journal is an anachronism. Digital technology enables us to communicate ideas far more rapidly than in the past and allows much greater levels of interaction between researchers. I agree with Daniel Shanahan that the future for many fields will be defined not in terms of “papers” which purport to represent “final” research outcomes, but by living documents continuously updated in response to open scrutiny by the community of researchers. I’ve long argued that the modern academic publishing industry is not facilitating but hindering the communication of research. The arXiv has already made academic journals virtually redundant in many of branches of physics and astronomy; other disciplines will inevitably follow. The age of the academic journal is drawing to a close. Now to rethink the concept of “the paper”…