News broke yesterday that the Minister responsible for Universities and Science within the Department of Business, Innovation and Skills, David Willetts, had stepped down from his role and would be leaving Parliament at the next election.

Willetts’ departure isn’t particularly surprising in itself, but its announcement came along with a host of other sackings and resignations in a pre-Election cabinet reshuffle that was much wider in its scope than most expected. It seems to me that Prime Minster David Cameron has decided to play to the gallery again. After almost four years in which his Cabinet has been dominated by white males, most of them nondescript timeserving political hacks without beards, he has culled some of them at random to try to pretend that he does after all care about equality and diversity. Actually, I don’t think David Cameron cares for very much at all apart from his own political future and this is just a cynical attempt to win back some votes before the next Polling Day, presumably in May 2015. Rumour has it that one of the new Cabinet ministers may even have facial hair. Such progress.

David Willetts was planning to step down at the next General Election anyway so his departure now was pretty much inevitable. I never agreed with his politics, but have to admit that he was a Minister who at least understood some things about Higher Education. In particular he knew the value of science and secured a flat cash settlement for the science budget at a time when other Whitehall budgets were suffering drastic cuts. He was by no means all bad. He even had the good taste – so I’m told – to read this blog from time to time….

The campaigning organization Science is Vital has expressed its sadness at his departure:

We’re sorry to see David Willetts moved from the Science Minister role. He listened, in person, to our arguments for increasing public funding for science, and we appreciated the support he showed for science within the government.

We look forward to renewed dialogue with his successor, in order to continue to press the case that science is vital for the UK.

Now that he has gone, my main worry is that the commitments he gave to ring-fence the science budget will go with him. I don’t know anything about his replacement, Greg Clark, though I hope he follows his predecessor at least in this regard.

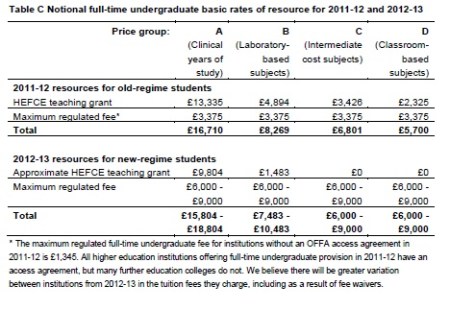

Other aspects of Willetts’ tenure of the Higher Education office are much less positive. He has provided over an ideologically-driven rush to force the University sector into an era of chaos and instability, driven by a rigged quasi-market propelled by an unsustainable system of tuition fees funded by student loans, a large fraction of which will never be repaid.

Another of Willetts’ notable failures relates to Open Access. Although apparently grasping the argument and make all the right noises about breaking the stranglehold exerted on academia by outmoded forms of publication, he sadly allowed the agenda to be hijacked by vested interests in the academic publishing lobby. Fortunately, there’s still a very strong chance that academics can take this particular issue into their own hands instead of relying on the politicians who time and time again prove themselves to be in the pockets of big business.

My biggest fear for Higher Education at the moment is that the new Minister will turn out to be far worse and that if the Conservatives win the next election (which is far from unlikely), Science is Vital will have to return to Whitehall to protest against the inevitable cuts. If that happens, it may well be that David Willetts is remembered not as the man who saved British science, but the man who gave it a stay of execution.

Follow @telescoper