Last week I was chatting to one of my colleagues about old films, particularly those made in the immediate post-war years by Ealing Studios. Nowadays this film production company is most strongly associated with superb comedy films, including such classics as Passport to Pimlico, Whisky Galore, The Ladykillers and The Lavender Hill Mob among many more. But there was more to Ealing Studios than the Ealing Comedies. During the war the company was involved in making propaganda films to help with the war effort, most of which are now forgettable but at least one, Went the Day Well, about people in an English village attempting to resist ruthless German paratroopers, is genuine shocking to this day because of its unusually frank depiction (for the time) of brutality and violence in a normally tranquil and familiar setting. The image of Thora Hird taking on the invaders with a Lee Enfield rifle is one that stays in my mind.

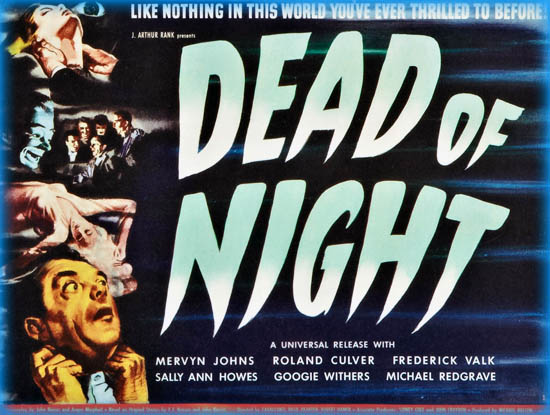

Horror films were banned during the War but in 1945 Ealing Studios released one which was to become enormous influential in the genre and which holds up extremely well to this day. As a matter of fact, I watched it again, for the umpteenth time, last night.

I’ve actually blogged about a bit of this film before. There is a sequence (to me by far the scariest in the film) about a ventriloquist (played by Michael Redgrave) who is gradually possessed by his evil dummy which came up in a post I did about Automatonophobia many moons ago.

Anyway, you only have to watch Dead of Night to watch it to appreciate why it its held in such high regard by critics to this day. Indeed you can see ideas in it which have been repeated in a host of subsequent (and usually inferior) horror flicks. I’m not going to spoil it by saying too much about the plot. I would say though that it’s basically a portmanteau film, i.e. a series of essentially separate stories (to the extent of having a different director for each such segment) embedded within an overall narrative. It also involves an intriguing plot device similar to those situations in which you are dreaming, but in the dream you wake up and don’t know whether you’re actually awake or still dreaming.

In this film the architect Walter Craig arrives at a country cottage, is greeted by his host Elliot Foley who has invited him to discuss possible renovations of the property. He is shown into a room with several other guests. Despite apparently never having been to the property before it seems strangely familiar and despite never having met the guests before he says he has seen them all in a recurring dream. One by one the guests recount strange stories. When they’ve all had their turn the film reaches a suitably nightmarish ending but Craig then wakes up in bed at home and realizes it was all a dream. Then the phone rings and it’s Elliot Foley inviting him to his country cottage to discuss possible renovations. The film ends with Craig arriving at the cottage just as he did at the start of the film.

Here is the trailer:

It’s the “dream-within-a-dream” structure (presumably repeated forever) – what physicists would call a self-similar hierarchy – of the overall framework of this movie that gives it its particular interest from the point of view of this blog, because it played an important role in the evolution of theoretical cosmology. One evening in 1946 the mathematicians and astrophysicts Fred Hoyle, Hermann Bondi and Tommy Gold went to see Dead of Night in Cambridge. Discussing the film afterwards they came up with the idea of the steady state cosmology, the first scientific papers about which were published in 1948. For the best part of two decades this theory was a rival to the now-favoured “Big Bang” (a term coined by Fred Hoyle which was intended to be a derogatory description of the opposing theory).

In the Big Bang theory there is a single “creation event”, so this particular picture of the Universe has a definite beginning, and from that point the arrow of time endows it with a linear narrative. In the steady state theory, matter is created continuously in small bits (via a hypothetical field called the C-field) so the Universe has no beginning and its time evolution not unlike that of the film.

Modern cosmologists sometimes dismiss the steady state cosmology as a bit of an aberration, a distraction from the One True Big Bang but it was undeniably a beautiful theory. The problem was that so many of its proponents refused to accept the evidence that they were wrong. Supporters of disfavoured theories rarely change their minds, in fact. The better theory wins out because younger folk tend to support it, while the recalcitrant old guard defending theirs in spite of the odds eventually die out.

And another thing. If Fred Hoyle had thought of it he might have called the field responsible for creating matter a scalar field, rather than the C-field, and it would now be much more widely recognized that he (unwittingly) invented many elements of modern inflationary cosmology. In fact, in some versions of inflation the Universe as a whole is very similar to the steady state model, only the continuous creation is not of individual particles or atoms, but of entire Big-Bang “bubbles” that can grow to the size of our observable Universe. So maybe the whole idea was actually right after all..

Follow @telescoper