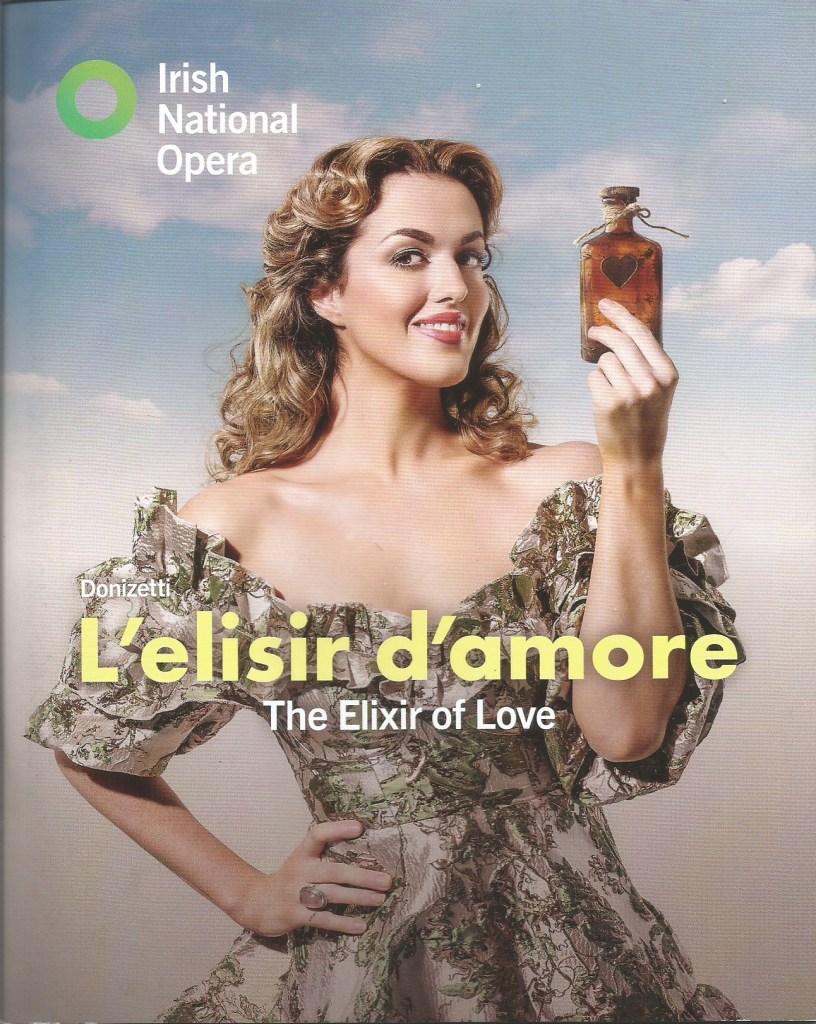

My trip to Wexford was to mark a special occasion by paying my first ever visit to the National Opera House to see a performance of Donizetti’s comic opera L’elisir d’amore by Irish National Opera. It was well worth the trip, as it was a wonderfully entertaining production with lovely singing and lots of laugh-out-loud moments. In short, it was a blast.

Billed as a melodramma giocoso, but more usually called an opera buffa, this was the first Donizetti opera to be performed in Ireland, in 1838; its world premiere was in 1832 in Milan and it has been in the operatic repertoire ever since. The show-stopping Una furtiva lagrima in Act II is one of the most recorded tenor arias, the first recording of which dates back to 1904 (by Enrico Caruso).

In case you’re not aware of the opera, it tells the story of a lowly peasant (Nemorino, tenor) who is in love with the wealthy Adina (soprano), who does not return his love – understandably not just because he’s poor but because he’s a bit of a drip. In despair Nemorino turns to the fake doctor Dulcamara (bass-baritone) “famous throughout the Universe and certain other places” who has arrived in town to peddle potions and quack remedies, no doubt made from snake oil. Nemorino asks him for a philtre that will make Adina fall for him. Dulcamara has sold all his potions, but fills an empty medicine bottle with wine and tells him it’s the love potion he needs. After drinking it, Nemorino feels more confident, but Adina still isn’t interested. Worse, Adina has agreed to marry to soldier Belcore. That’s Act I.

In Act II, desperate to stop the marriage, Nemorino wants to buy some more of the love potion but he has no money so he agrees to join the army for which he is entitled to a joining fee. He spends the money on more wine and gets completely wasted, so much so that he misses the news that a rich uncle has died and left him a large inheritance. When the women of the town find out that he is now rich, they all start showing an interest in Nemorino, which he assumes is because of the love-potion. At this point Adina decides she really does love Nemorino, buys out his contract with the army, and calls off the wedding with Belcore. The soldier shrugs off his loss. Dulcamara convinces himself that he really has magical powers…

Summarizing the plot doesn’t really do justice to the opera, however, as there are numerous musical interludes, with dancing, and slapstick comedy. Donizetti’s music is wonderful, and keeps the pace going. It’s basically a theatrical farce set to music, with the score keeping everything moving at the speed that is essential to make such a thing work. Erina Tashima conducted the Orchestra of Irish National Opera with great verve.

This production is set in a comical Wild West of America, with a relatively simple set but wonderful very witty costumes. Nemorino (Duke Kim) was dressed like Woody from Toy Story, for example. We also had appearances from Calamity Jane, Laurely & Hardy (who do their “Way Out West” dance), Abraham Lincoln and even the couple from Grant Wood’s painting American Gothic. Adina (Claudia Boyle) has no fewer than five costume changes, each one into a frock more glamorous than the previous. Dulcamara was the wonderful John Molloy and there is great comedy between him and his diminutive sidekick Truffaldino (a non-singing part played by Ian O’Reilly). Belcore’s troops are kitted out like the US Cavalry, and their dancing and messing about delivers laugh after laugh. There are also sundry “peasants”, i.e. cowboys and women of the town adding to the hilarity. I give 10/10 to the members of the chorus, their Director Richard McGrath and choreographer Paula O’Reilly.

All the principles were great too. Claudia Boyle sang beautifully, but also conveyed the comic aspects of her role. Duke Kim was perfectly cast as the boyish Nemorino; he has a light and agile tenor voice, which he used to bring the house down with the big number Una Furtiva Lagrima in Act II. Belcore was baritone Gianluca Margheri (whom I saw perform in Maynooth a couple of years ago). His physique matches the muscular quality of his voice, and he wasn’t shy in showing it off by taking off his shirt onstage! John Molloy’s singing was as impeccable as his comic timing in the role of Dulcamara. I think he got the most laughs, in a production that produced many.

This triumphant production plays L’elisir d’amore for laughs and wins by a knockout. Sadly there’s only one performance left in this run, in Cork on Saturday 7th June. Do go if you can!