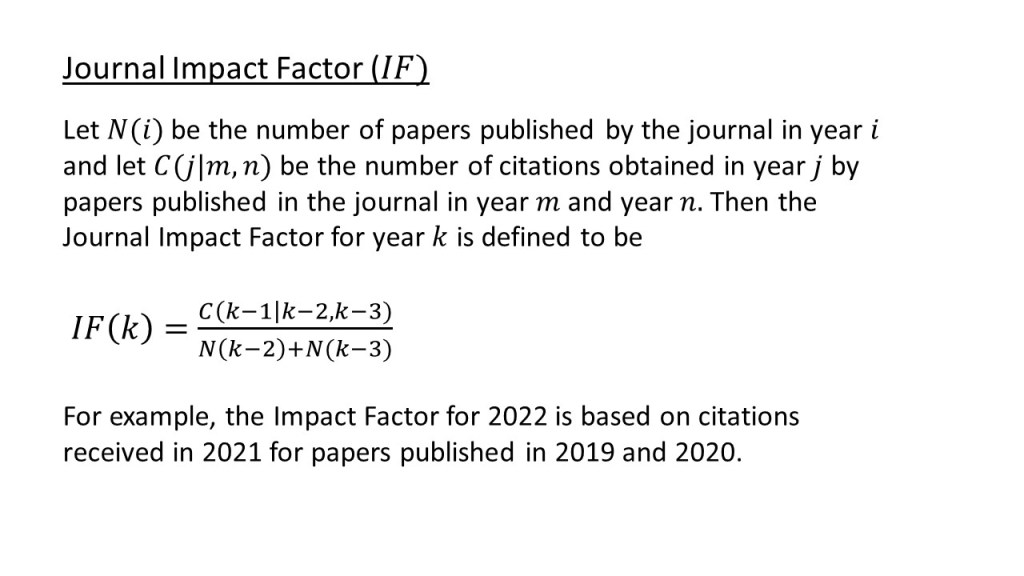

I was at a meeting this morning in which the vexed issue of the journal Impact Factor (IF) came up. That reminded me of something that struck me when I was checking the NASA/ADS entry for a paper recently published by the Open Journal of Astrophysics, and I thought it would be worth sharing it here. First of all, here’s a handy slide showing how the Impact Factor (IF) for a journal is calculated for a given year:

It’s a fairly straightforward piece of information to calculate, which is one of its few virtues.

Now consider this paper we recently published in the Open Journal of Astrophysics:

As of today, according to the wonderful NASA/ADS system, this paper has 36 citations. That’s no bad considering that it was published less than a month ago. It’s obviously already quite an impactful paper. The problem is that if you look at the recipe given above you will see that none of those 36 citations – nor any more that this paper receives this year – will ever be included in the calculation of the Impact Factor for the Open Journal of Astrophysics. Only citations to this paper garnered in 2024 and 2025 will count to the impact factors (for 2025 and 2026 respectively). There’s every reason to think this paper will get plenty of citations over the next two years, but I think this demonstrates another bit of silliness to add to the already long list of silly things about the IF as a measure of citation impact.

My view of citation numbers is that they do contain some (limited) information about an article’s impact, but if you want to use them you should just use the citations for the article itself, not a peculiar and arbitrarily-constructed proxy like the IF. It is so easy to get article-level citation data that there is simply no need to use a journal-level metric for anything at all.