Day Two of this enjoyable meeting involved more talks about the cosmic web of large-scale structure of the Universe. I’m not going to attempt to summarize the whole day, but will just mention a couple of things that made me reflect a bit. Unfortunately that means I won’t be able to do more than merely mention some of the other fascinating things that came up, as phase-space flip-flops and one-dimensional Origami.

One was a very nice review by John Peacock in which he showed that a version of Moore’s law applies to galaxy redshift surveys; since the first measurement of the redshift of an extragalactic object by Slipher in 1912, the number of redshifts has doubled every 2-3 years ago. This exponential growth has been driven by improvements in technology, from photographic plates to electronic detectors and from single-object spectroscopy to multiplex technology and so on. At this rate by 2050 or so we should have redshifts for most galaxies in the observable Universe. Progress in cosmography has been remarkable indeed.

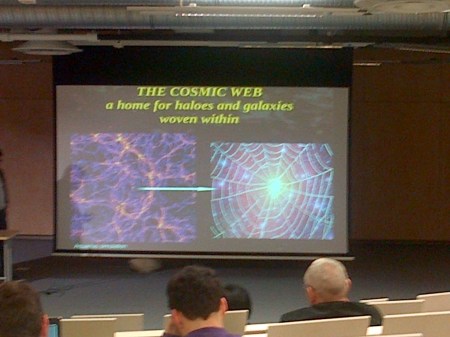

The term “Cosmic Web” may be a bit of a misnomer in fact, as a consensus may be emerging that in some sense it is more like a honeycomb. Thanks to a miracle of 3D printing, here is an example of what the large-scale structure of the Universe seems to look like:

One of the issues that emerged from the mix of theoretical and observational talks concerned the scale of cosmic homogeneity. Our standard cosmological model is based on the Cosmological Principle, which asserts that the Universe is, in a broad-brush sense, homogeneous (is the same in every place) and isotropic (looks the same in all directions). But the question that has troubled cosmologists for many years is what is meant by large scales? How broad does the broad brush have to be? A couple of presentations discussed the possibly worrying evidence for the presence of a local void, a large underdensity on scale of about 200 MPc which may influence our interpretation of cosmological results.

I blogged some time ago about that the idea that the Universe might have structure on all scales, as would be the case if it were described in terms of a fractal set characterized by a fractal dimension . In a fractal set, the mean number of neighbours of a given galaxy within a spherical volume of radius

is proportional to

. If galaxies are distributed uniformly (homogeneously) then

, as the number of neighbours simply depends on the volume of the sphere, i.e. as

, and the average number-density of galaxies. A value of

indicates that the galaxies do not fill space in a homogeneous fashion:

, for example, would indicate that galaxies were distributed in roughly linear structures (filaments); the mass of material distributed along a filament enclosed within a sphere grows linear with the radius of the sphere, i.e. as

, not as its volume; galaxies distributed in sheets would have

, and so on.

We know that on small scales (in cosmological terms, still several Megaparsecs), but the evidence for a turnover to

has not been so strong, at least not until recently. It’s just just that measuring

from a survey is actually rather tricky, but also that when we cosmologists adopt the Cosmological Principle we apply it not to the distribution of galaxies in space, but to space itself. We assume that space is homogeneous so that its geometry can be described by the Friedmann-Lemaitre-Robertson-Walker metric.

According to Einstein’s theory of general relativity, clumps in the matter distribution would cause distortions in the metric which are roughly related to fluctuations in the Newtonian gravitational potential by

, give or take a factor of a few, so that a large fluctuation in the density of matter wouldn’t necessarily cause a large fluctuation of the metric unless it were on a scale

reasonably large relative to the cosmological horizon

. Galaxies correspond to a large

but don’t violate the Cosmological Principle because they are too small in scale

to perturb the background metric significantly.

The discussion of a fractal universe is one I’m overdue to return to. In my previous post I left the story as it stood about 15 years ago, and there have been numerous developments since then, not all of them consistent with each other. I will do a full “Part 2” to that post eventually, but in the mean time I’ll just comment that current large surveys, such as those derived from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, do seem to be consistent with a Universe that possesses the property of large-scale homogeneity. If that conclusion survives the next generation of even larger galaxy redshift surveys then it will come as an immense relief to cosmologists.

The reason for that is that the equations of general relativity are very hard to solve in cases where there isn’t a lot of symmetry; there are just too many equations to solve for a general solution to be obtained. If the cosmological principle applies, however, the equations simplify enormously (both in number and form) and we can get results we can work with on the back of an envelope. Small fluctuations about the smooth background solution can be handled (approximately but robustly) using a technique called perturbation theory. If the fluctuations are large, however, these methods don’t work. What we need to do instead is construct exact inhomogeneous model, and that is very very hard. It’s of course a different question as to why the Universe is so smooth on large scales, but as a working cosmologist the real importance of it being that way is that it makes our job so much easier than it would otherwise be.

PS. If anyone reading this either at the conference or elsewhere has any questions or issues they would like me to raise during the summary talk on Saturday please don’t hesitate to leave a comment below or via Twitter using the hashtag #IAU308.

Follow @telescoper