Today’s the day that over 60,000 school students across Ireland are receiving their Leaving Certificate Results. As always there will be joy for some, and disappointment for others. The headline news relating to these results is that a majority (68%) of grades have been scaled up to that the distribution matches last year’s outcomes. This has meant an uplift of marks by about 7.5% on average, with the biggest changes happening at the lower levels of grade.

This artificial boost is a consequence of the generous adjustments made during the pandemic and apparent wish by the Education Minister, Norma Foley, to ensure that this year’s students are treated “fairly” compared to last year’s. Of course this argument could be made for continuing to inflate grades next year too, and the year after that. Perhaps the Minister’s plan seems to be to keep the grades high until after the next General Election, after which it will be someone else’s job to treat students “unfairly”. Anyway, you might say that marks have been scaled to maintain a Norma Distribution…

One can’t blame the students, of course, but one of the effects of this scaling is that students will be coming into third-level education with grades that imply a greater level of achievement than they actually have reached. This is a particular problem with a subject like physics where we really need students to be comfortable with certain aspects of mathematics before they start their course. It has been clear that even students with very good grades at Higher level have considerable gaps in their knowledge. This looks set to continue, and we will just have to deal with it. This issue was compounded for a while because Leaving Certificate grades were produced so late that first-year students had to start university a week late, giving less time for the remedial teaching that many of them needed. At least this year we won’t have that problem, so can plan some activities early on in the new Semester.

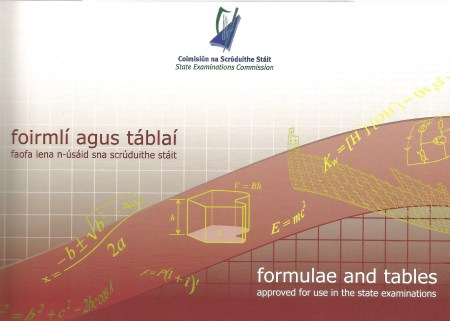

Anyway, out of interest – probably mine rather than yours – I delved into the statistics of Leaving Certificate results going back six years for Mathematics (at Higher A and Ordinary B) level, Physics and Applied Mathematics which I fished out of the general numbers given here.

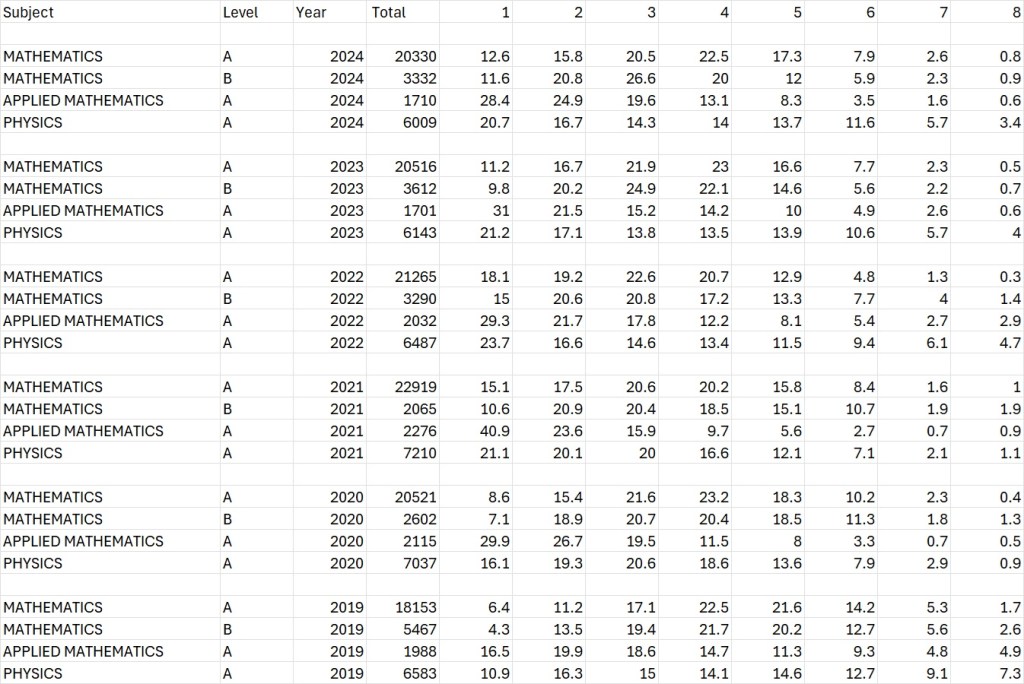

Here are the results in a table, with the columns denoting the grade (1=high) and the numbers are percentages:

You can seen that the percentage of students getting H1 in Mathematics has increased a bit to 12.6% after falling considerably from 18.1% in 2022 to 11.2% last year (2023); note the huge increase in H1 from 2020 to 2021 (8.6% to 15.1%). Another thing worth noting is that both Physics and Applied Mathematics have declined significantly in popularity since 2019 from 7210.

Now that the results are out there will be a busy time until next Wednesday (28th) when the CAO first round offers go out. That is when those students wanting to go to university find out if they made the grades and university departments find out how many new students (if any) they will have to teach in September.

P.S. When I was a little kid we used to call a “Certificate” a “Stiff Ticket”. I just thought you would like to know that.