I am remiss in having forgotten until now to circulate an open letter that has been set up to express support for the high energy physics theory and particle theory communities in the United Kingdom. I signed the letter a few days ago but neglected to circulate it for further signature.

The letter reads:

We the undersigned wish to raise serious concerns about the current cuts to UK high energy particle physics theory grants by signing up to the letter below. The open letter and list of signatories are printed on this page. Individuals who wish to support this initiative may add their name as a signatory by completing the form below. This letter will be sent to Lord Patrick Vallance (Minister of State for Science, Innovation, Research and Nuclear), Liz Kendall (Secretary of State for Science, Innovation and Technology), Chi Onwurah MP (Chair of the UK House of Commons Science, Innovation and Technology Select Committee), and Prof. Sir Ian Chapman (CEO of UKRI).

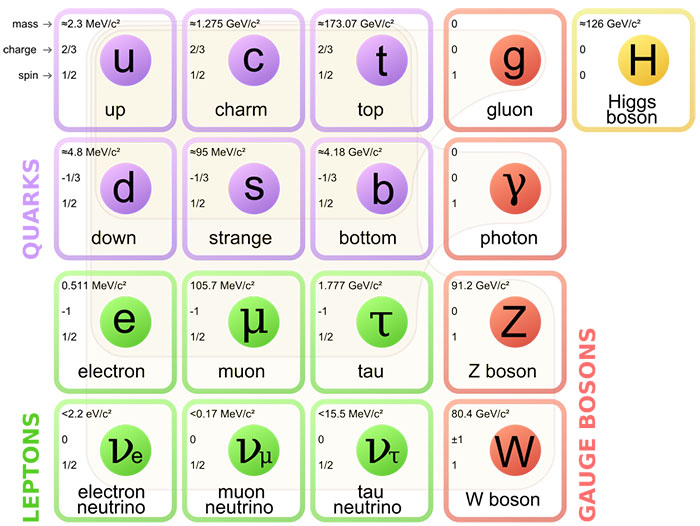

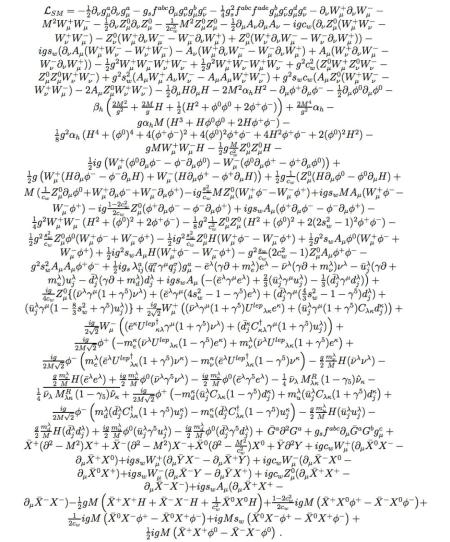

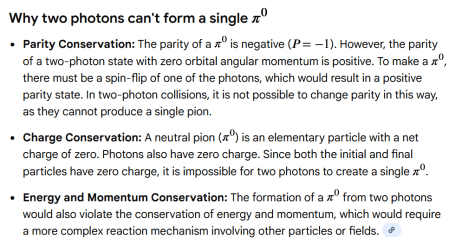

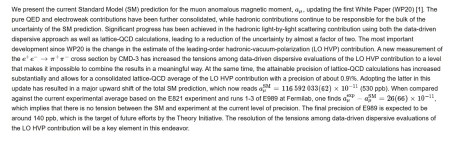

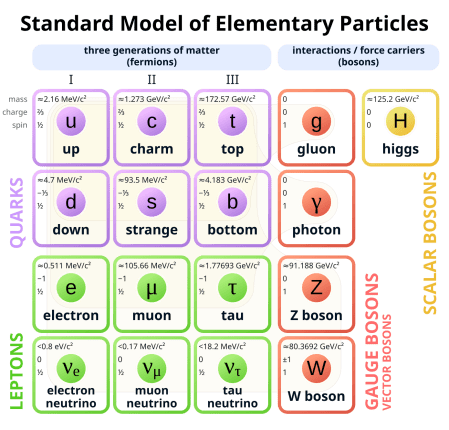

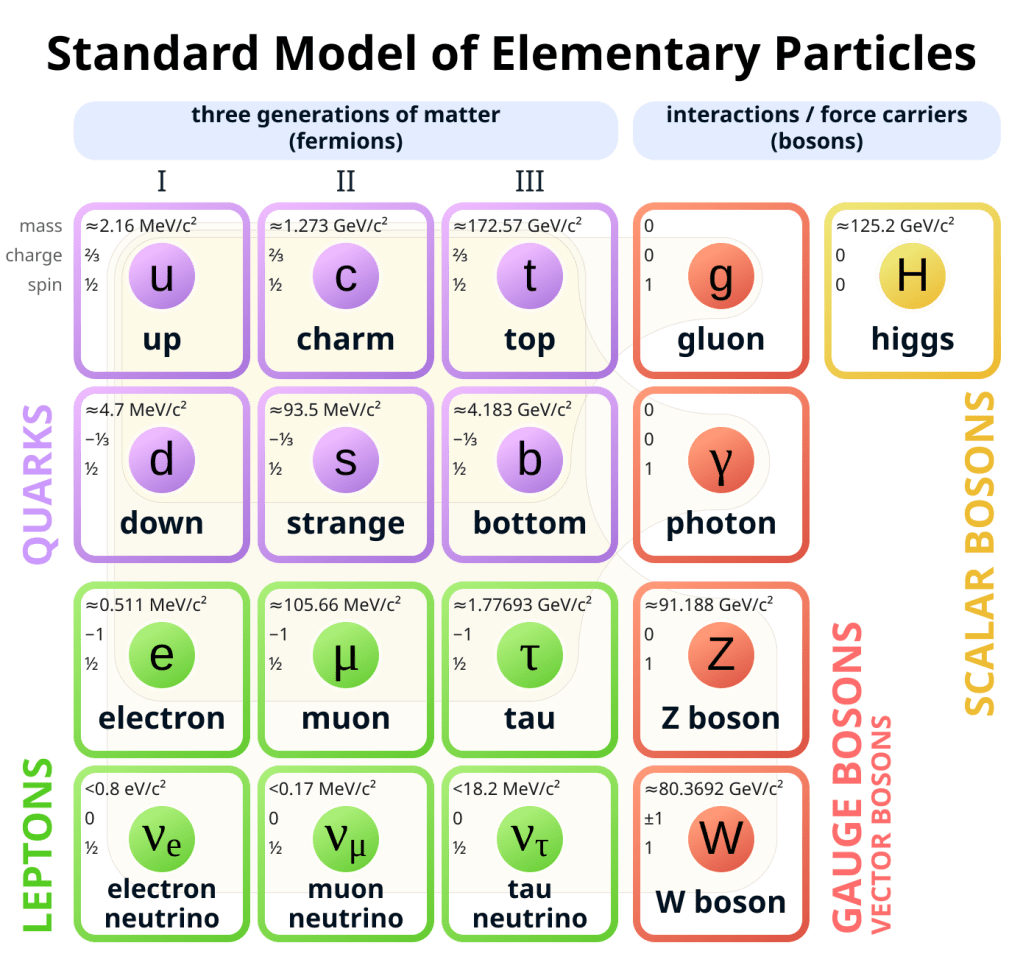

We are signing this letter to raise serious concerns about the proposed cuts to high energy physics theory and particle theory in the United Kingdom. The UK is a world leader in this area: its historical activity led to the development of the Standard Model of particle physics and the ongoing development of string theory. UK theoretical physicists provide essential input to major international experiments, including the Large Hadron Collider at CERN and next-generation programmes in neutrino physics, gravitational waves, and cosmology, enabling rigorous interpretation of data and the extraction of fundamental insight. The strength of the UK community lies in its intellectual breadth and integration: researchers operate across phenomenology, formal theory, and their interface, and sustained dialogue between these areas underpins the UK’s leading role in global collaborations and internationally recognised research groups. In parallel, UK theorists advance the theoretical foundations of fundamental physics.

These groups and scientists can only operate thanks to critical funding by UK research council funding.

The current apparent scale of the cuts to the Particle Physics, Astronomy and Nuclear Physics area (30% to the overall budget) will result, when rising costs are taken into account, in a much greater than 50% cut in the number of postdoctoral researchers active in these areas in the UK. This will have a devastating effect on the ability of the UK to maintain its leading role in the subject.

Such funding decisions will affect the famously excellent reputation of the UK university sector. It will risk the health of UK physics departments and will therefore damage economic growth in the UK. Many scientists trained in this sector subsequently move into senior positions in technical industries such as machine learning and finance. Theorists at universities play a crucial role in the training and development of the inventors and disruptors of the future.

We urge UK politicians and leaders in the UK funding organisations to carefully consider the implications of the current direction of funding decisions before it is too late and irreparable damage is done to the UK theory community.

You can sign the letter and see a list of existing signatories here.