Archive for Topology

If Oscar Wilde were a Torus

Posted in mathematics with tags genus, Oscar Wilde, quotations, Topology, torus on March 3, 2025 by telescoperThe Return of a Small Universe?

Posted in The Universe and Stuff with tags arXiv:2309.03272, Cosmology, Jean-Luc Lehners, small universe, Topology on October 5, 2023 by telescoperToday I attended a cosmology discussion group where the paper being considered was by Jean-Luc Lehners and Jerome Quintin and was entitled A small Universe. Here is the abstract:

Many cosmological models assume or imply that the total size of the universe is very large, perhaps even infinite. Here we argue instead that the universe might be comparatively small, in fact not much larger than the currently observed size. A concrete implementation of this idea is provided by the no-boundary proposal, in combination with a plateau-shaped inflationary potential. In this model, opposing effects of the weighting of the wave function and of the criterion of allowability of the geometries conspire to favour small universes. We point out that a small size of the universe also fits well with swampland conjectures, and we comment on the relation with the dark dimension scenario.

arXiv:2309.03272

This paper is based on rather speculative arguments. I don’t have anything against those, but the discussion of this particular case reminded me that the idea that the Universe might be much smaller than we think is one that has come and gone many times during my lifetime. The point is that Einstein’s equations of general relativity are local in that they relate the geometric properties of space-time at specific coordinate position to the energy and momentum at the same position. When we make cosmological models based on these equations we usually assume a great deal of symmetry, i.e. that defined in a certain way the spatial sections which form surfaces of simultaneity have the same curvature everywhere, regardless of spatial position. The standard cosmology takes this curvature to be zero, in fact, so the spatial sections are Euclidean (flat), though the curvature could be positive or negative.

Usually when we assume the universe is flat we also assume that it is infinite, but it is possible in principle that a flat universe could be finite, for example in the case of a cube with opposite faces identified so that it has a sort of toroidal symmetry that has no physical edge. The size of the notional cube defines a topological scale which is independent of Einstein’s equations. That’ just a simple example: the topology does not have to be based on a cube; it could be, for example, a rhombic dodecahedron…

Likewise when we talk about a universe with negative spatial curvature we also assume it to be infinite, but that doesn’t have to be the case either: there are spaces with negative spatial curvature which are finite. A manifestation of this idea that I remember from way back in 1999 was a paper by Neil Cornish and David Spergel entitled A small universe after all?

Observing a small universe from the inside produces many interesting effects like a sort of cosmic hall of mirrors. For instance, if you can see far enough you will see the back of your own head. More realistically, the observed large-scale structure of the universe would repeat, and there would be correlated features in the cosmic microwave background. The idea is therefore amenable to observational test; the absence of any of the predicted correlations places constrains the topological scale to be comparable to the size of the observable universe or larger. Of course if it’s infinitely large then the small universe is not small at all…

(For a bit of gratuitous self-promotion, I refer you to a paper I wrote with Graca Rocha and Patrick Dineen back in 2004 using the WMAP observations of the CMB to constrain compact topologies. Given the wealth of new data we have acquired since then I’m sure the constraints are even stronger now.)

Anyway, my point is that speculative ideas are all very well but they don’t mean much if you can’t test them. This one at least has the virtue of making testable predictions.

Sizes, Shapes and Minkowski Functionals

Posted in mathematics, The Universe and Stuff with tags Cosmology, Euler-Poincaré, genus, Minkowski Functionals, Topology on August 27, 2022 by telescoperBefore I forget I thought I would do a brief post on the subject of Minkowski Functionals, as used in the paper we recently published in the Open Journal of Astrophysics. As as has been pointed out, the Wikipedia page on Minkowski Functionals is somewhat abstract and impenetrable so here is a much simplified summary of their application in a cosmological setting.

One of things we want to do with a cosmological data set to characterize its statistical properties to compare theoretical predictions with observations. One interesting way of doing this is to study the morphology of the patterns involved using quantitative measures based on topology.

The approach normally used deals with Excursion Sets, i.e. regions where a field exceeds a certain level usually given in terms of the rms fluctuation or defined by the fraction of space above the threshold. The field could, for example, be the temperature field on the CMB Sky or the density field traced by galaxies. In general the excursion set will consist of a number of disjoint pieces which may be simply or multiply connected. As the threshold is raised, the connectivity of the excursion set will shrink but also its connectivity will change, so we need to study everything as a function of threshold to get a full description.

One can think of lots of ways of defining measures related to an excursion set. The Minkowski Functionals are the topological invariants that satisfy four properties:

- Additivity

- Continuity

- Rotation Invariance

- Translation Invariance

In D dimensions there are (D+1) invariants so defined. In cosmology we usually deal with D=2 or D=3. In 2D, two of the characteristics are obvious: the total area of the excursion set and the total length of its boundary (perimeter). These are clearly additive.

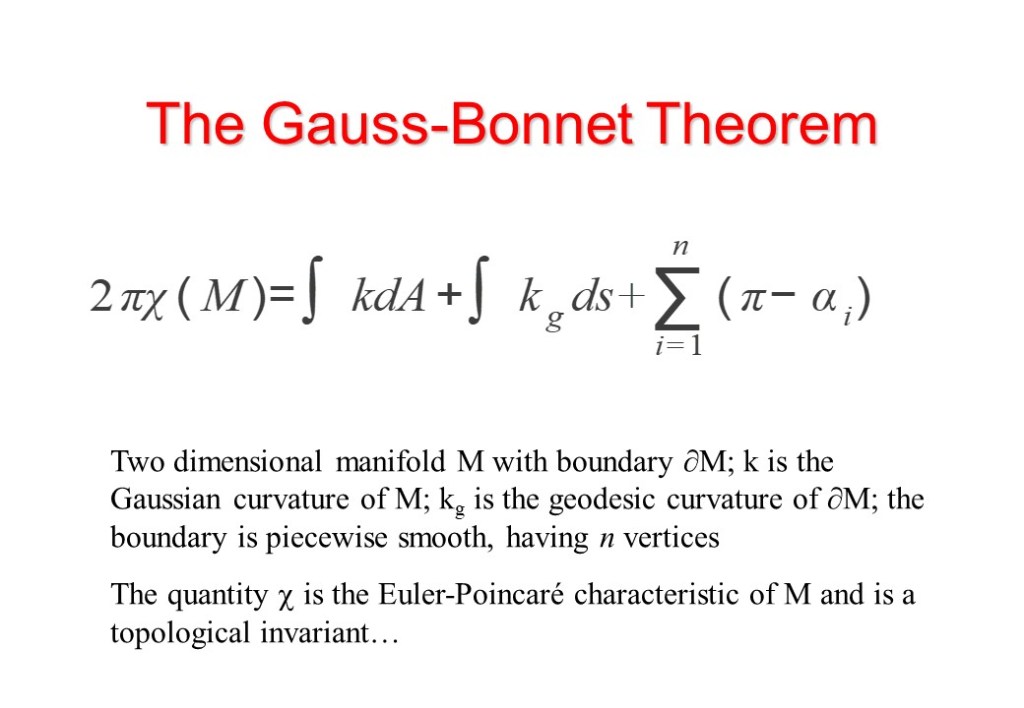

In order to understand the third invariant we need to invoke the Gauss-Bonnet theorem, shown in this graphic:

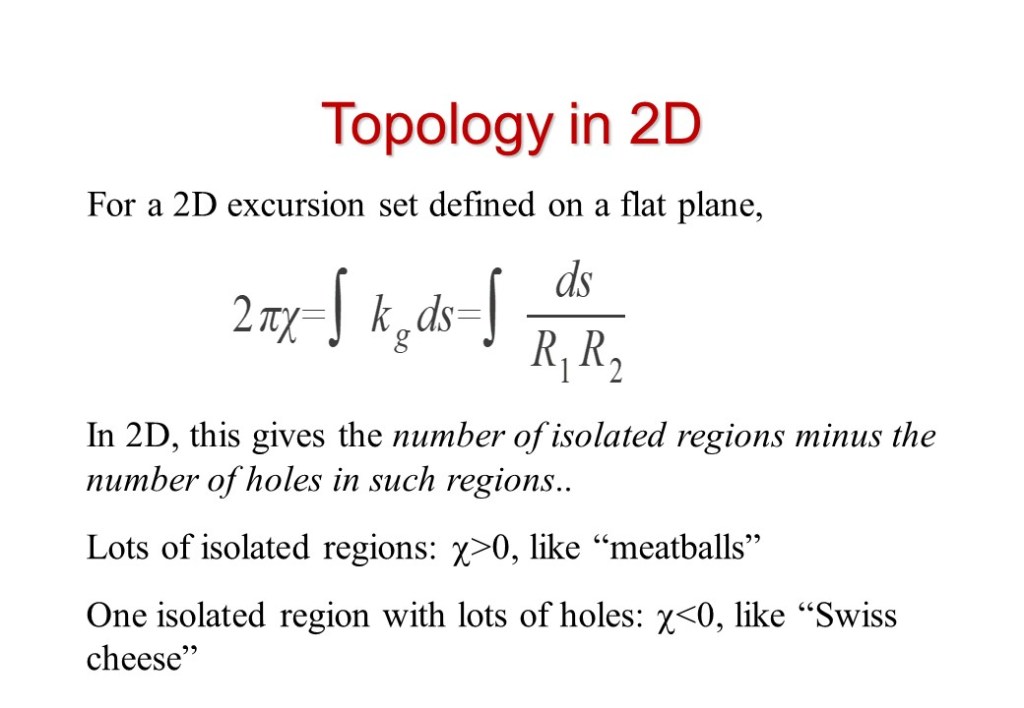

The Euler-Poincare characteristic (χ) is our third invariant. The definition here allows one to take into account whether or not the data are defined on a plane or curved surface such as the celestial sphere. In the simplest case of a plane we get:

As an illustrative example consider this familiar structure:

Instead of using a height threshold let’s just consider the structure defined by land versus water. There is one obvious island but in fact there are around 80 smaller islands surrounding it. That illustrates the need to define a resolution scale: structures smaller than the resolution scale do not count. The same goes with lakes. If we take a coarse resolution scale of 100 km2 then there are five large lakes (Lough Neagh, Lough Corrib, Lough Derg, Lough Ree and Lower Lough Erne) and no islands. At this resolution, the set consists of one region with 5 holes in it: its Euler-Poincaré characteristic is therefore χ=-4. The change of χ with scale in cosmological data sets is of great interest. Note also that the area and length of perimeter will change with resolution too.

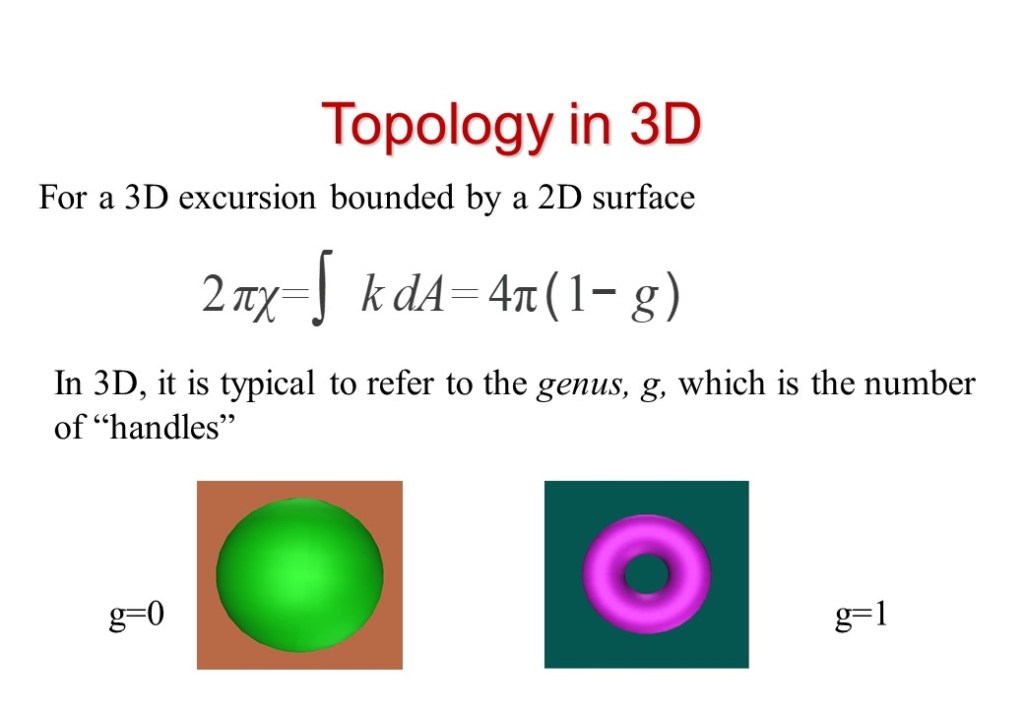

One can use the Gauss-Bonnet theorem to extend these considerations to 3D by applying to the surfaces bounding the pieces of the excursion set and consequently defining their corresponding Euler-Poincaré. characteristics, though for historical reasons many in cosmology refer not to χ but the genus g.

A sphere has zero genus (χ=1) and torus has g=1 (χ=0).

In 3D the four Minkowski Functionals are: the volume of the excursion set; the surface area of the boundary of the excursion set; the mean curvature of the boundary; and χ (or g).

Great advantage of these measures is that they are quite straightforward to extract from data (after suitable smoothing) and their mean values are calculable analytically for the cosmologically-relevant case of a Gaussian random field.

Here endeth the lesson.

How to make a knotted vortex ring

Posted in The Universe and Stuff with tags Knots, Physics, Topology, University of Chicago, Vortex Rings on May 15, 2013 by telescoperNot long ago I posted a short item about the physics of vortex rings. More recently I stumbled across this video that shows how University of Chicago physicists have succeeded in creating a vortex knot—a feat akin to tying a smoke ring into a knot. Linked and knotted vortex loops have existed in theory for more than a century, but creating them in the laboratory had previously eluded scientists. I stole that bit shamelessly from the blurb on Youtube, by the way. I’m not sure whether knotting a vortex tube has any practical applications, but then I don’t really care much about that because it’s fun!

Topological Escapology

Posted in Education, The Universe and Stuff with tags Physics, Topology on June 13, 2011 by telescoperThe occasional teasers I post on here seem to go down quite well so I thought I’d try this one on you. I recently found it in an old book on the topic of topology, a fascinating field that finds many applications in physics, including several in my own field of cosmology.

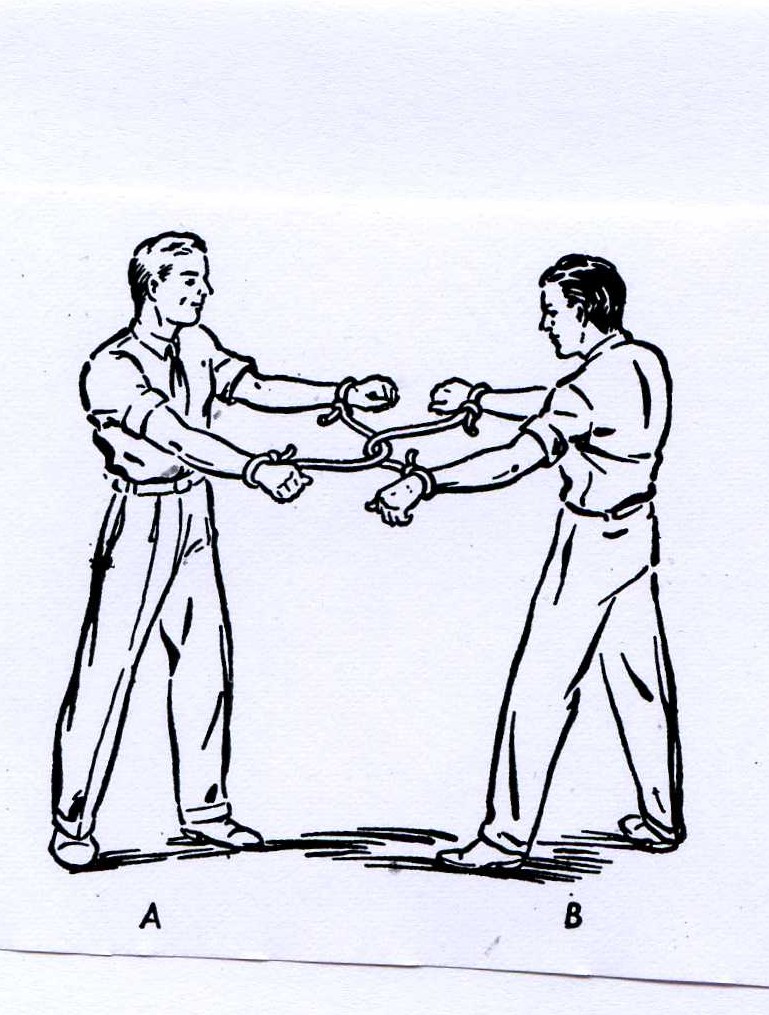

It’s probably best not to ask why, but the two gentlemen in the picture, A and B, are tied together in the following way. One end of a piece of rope is tied about A’s right wrist, the other about his left wrist. A second rope is passed around the first and its ends are tied to B’s wrists.

Can A and B free each other without cutting either rope, performing amputations, or untying the knots at either person’s wrists?

If so, how?