I don’t mind admitting that as I get older I get more and more pessimistic about the prospects for humankind’s survival into the distant future.

Unless there are major changes in the way this planet is governed, our planet may become barren and uninhabitable through war or environmental catastrophe. But I do think the future is in our hands, and disaster is, at least in principle, avoidable. In this respect I have to distance myself from a very strange argument that has been circulating among philosophers and physicists for a number of years. It is called Doomsday argument, and it even has a sizeable wikipedia entry, to which I refer you for more details and variations on the basic theme. As far as I am aware, it was first introduced by the mathematical physicist Brandon Carter and subsequently developed and expanded by the philosopher John Leslie (not to be confused with the TV presenter of the same name). It also re-appeared in slightly different guise through a paper in the serious scientific journal Nature by the eminent physicist Richard Gott. Evidently, for some reason, some serious people take it very seriously indeed.

The Doomsday argument uses the language of probability theory, but it is such a strange argument that I think the best way to explain it is to begin with a more straightforward problem of the same type.

Imagine you are a visitor in an unfamiliar, but very populous, city. For the sake of argument let’s assume that it is in China. You know that this city is patrolled by traffic wardens, each of whom carries a number on their uniform. These numbers run consecutively from 1 (smallest) to T (largest) but you don’t know what T is, i.e. how many wardens there are in total. You step out of your hotel and discover traffic warden number 347 sticking a ticket on your car. What is your best estimate of T, the total number of wardens in the city?

I gave a short lunchtime talk about this when I was working at Queen Mary College, in the University of London. Every Friday, over beer and sandwiches, a member of staff or research student would give an informal presentation about their research, or something related to it. I decided to give a talk about bizarre applications of probability in cosmology, and this problem was intended to be my warm-up. I was amazed at the answers I got to this simple question. The majority of the audience denied that one could make any inference at all about T based on a single observation like this, other than that it must be at least 347.

Actually, a single observation like this can lead to a useful inference about T, using Bayes’ theorem. Suppose we have really no idea at all about T before making our observation; we can then adopt a uniform prior probability. Of course there must be an upper limit on T. There can’t be more traffic wardens than there are people, for example. Although China has a large population, the prior probability of there being, say, a billion traffic wardens in a single city must surely be zero. But let us take the prior to be effectively constant. Suppose the actual number of the warden we observe is t. Now we have to assume that we have an equal chance of coming across any one of the T traffic wardens outside our hotel. Each value of t (from 1 to T) is therefore equally likely. I think this is the reason that my astronomers’ lunch audience thought there was no information to be gleaned from an observation of any particular value, i.e. t=347.

Let us simplify this argument further by allowing two alternative “models” for the frequency of Chinese traffic wardens. One has T=1000, and the other (just to be silly) has T=1,000,000. If I find number 347, which of these two alternatives do you think is more likely? Think about the kind of numbers that occupy the range from 1 to T. In the first case, most of the numbers have 3 digits. In the second, most of them have 6. If there were a million traffic wardens in the city, it is quite unlikely you would find a random individual with a number as small as 347. If there were only 1000, then 347 is just a typical number. There are strong grounds for favouring the first model over the second, simply based on the number actually observed. To put it another way, we would be surprised to encounter number 347 if T were actually a million. We would not be surprised if T were 1000.

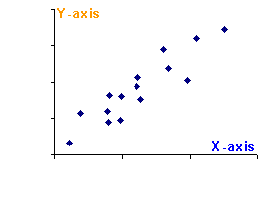

One can extend this argument to the entire range of possible values of T, and ask a more general question: if I observe traffic warden number t what is the probability I assign to each value of T? The answer is found using Bayes’ theorem. The prior, as I assumed above, is uniform. The likelihood is the probability of the observation given the model. If I assume a value of T, the probability P(t|T) of each value of t (up to and including T) is just 1/T (since each of the wardens is equally likely to be encountered). Bayes’ theorem can then be used to construct a posterior probability of P(T|t). Without going through all the nuts and bolts, I hope you can see that this probability will tail off for large T. Our observation of a (relatively) small value for t should lead us to suspect that T is itself (relatively) small. Indeed it’s a reasonable “best guess” that T=2t. This makes intuitive sense because the observed value of t then lies right in the middle of its range of possibilities.

Before going on, it is worth mentioning one other point about this kind of inference: that it is not at all powerful. Note that the likelihood just varies as 1/T. That of course means that small values are favoured over large ones. But note that this probability is uniform in logarithmic terms. So although T=1000 is more probable than T=1,000,000, the range between 1000 and 10,000 is roughly as likely as the range between 1,000,000 and 10,000,0000, assuming there is no prior information. So although it tells us something, it doesn’t actually tell us very much. Just like any probabilistic inference, there’s a chance that it is wrong, perhaps very wrong.

What does all this have to do with Doomsday? Instead of traffic wardens, we want to estimate N, the number of humans that will ever be born, Following the same logic as in the example above, I assume that I am a “randomly” chosen individual drawn from the sequence of all humans to be born, in past present and future. For the sake of argument, assume I number n in this sequence. The logic I explained above should lead me to conclude that the total number N is not much larger than my number, n. For the sake of argument, assume that I am the one-billionth human to be born, i.e. n=1,000,000,0000. There should not be many more than a few billion humans ever to be born. At the rate of current population growth, this means that not many more generations of humans remain to be born. Doomsday is nigh.

Richard Gott’s version of this argument is logically similar, but is based on timescales rather than numbers. If whatever thing we are considering begins at some time tbegin and ends at a time tend and if we observe it at a “random” time between these two limits, then our best estimate for its future duration is of order how long it has lasted up until now. Gott gives the example of Stonehenge[1], which was built about 4,000 years ago: we should expect it to last a few thousand years into the future. Actually, Stonehenge is a highly dubious . It hasn’t really survived 4,000 years. It is a ruin, and nobody knows its original form or function. However, the argument goes that if we come across a building put up about twenty years ago, presumably we should think it will come down again (whether by accident or design) in about twenty years time. If I happen to walk past a building just as it is being finished, presumably I should hang around and watch its imminent collapse….

But I’m being facetious.

Following this chain of thought, we would argue that, since humanity has been around a few hundred thousand years, it is expected to last a few hundred thousand years more. Doomsday is not quite as imminent as previously, but in any case humankind is not expected to survive sufficiently long to, say, colonize the Galaxy.

You may reject this type of argument on the grounds that you do not accept my logic in the case of the traffic wardens. If so, I think you are wrong. I would say that if you accept all the assumptions entering into the Doomsday argument then it is an equally valid example of inductive inference. The real issue is whether it is reasonable to apply this argument at all in this particular case. There are a number of related examples that should lead one to suspect that something fishy is going on. Usually the problem can be traced back to the glib assumption that something is “random” when or it is not clearly stated what that is supposed to mean.

There are around sixty million British people on this planet, of whom I am one. In contrast there are 3 billion Chinese. If I follow the same kind of logic as in the examples I gave above, I should be very perplexed by the fact that I am not Chinese. After all, the odds are 50: 1 against me being British, aren’t they?

Of course, I am not at all surprised by the observation of my non-Chineseness. My upbringing gives me access to a great deal of information about my own ancestry, as well as the geographical and political structure of the planet. This data convinces me that I am not a “random” member of the human race. My self-knowledge is conditioning information and it leads to such a strong prior knowledge about my status that the weak inference I described above is irrelevant. Even if there were a million million Chinese and only a hundred British, I have no grounds to be surprised at my own nationality given what else I know about how I got to be here.

This kind of conditioning information can be applied to history, as well as geography. Each individual is generated by its parents. Its parents were generated by their parents, and so on. The genetic trail of these reproductive events connects us to our primitive ancestors in a continuous chain. A well-informed alien geneticist could look at my DNA and categorize me as an “early human”. I simply could not be born later in the story of humankind, even if it does turn out to continue for millennia. Everything about me – my genes, my physiognomy, my outlook, and even the fact that I bothering to spend time discussing this so-called paradox – is contingent on my specific place in human history. Future generations will know so much more about the universe and the risks to their survival that they won’t even discuss this simple argument. Perhaps we just happen to be living at the only epoch in human history in which we know enough about the Universe for the Doomsday argument to make some kind of sense, but too little to resolve it.

To see this in a slightly different light, think again about Gott’s timescale argument. The other day I met an old friend from school days. It was a chance encounter, and I hadn’t seen the person for over 25 years. In that time he had married, and when I met him he was accompanied by a baby daughter called Mary. If we were to take Gott’s argument seriously, this was a random encounter with an entity (Mary) that had existed for less than a year. Should I infer that this entity should probably only endure another year or so? I think not. Again, bare numerological inference is rendered completely irrelevant by the conditioning information I have. I know something about babies. When I see one I realise that it is an individual at the start of its life, and I assume that it has a good chance of surviving into adulthood. Human civilization is a baby civilization. Like any youngster, it has dangers facing it. But is not doomed by the mere fact that it is young,

John Leslie has developed many different variants of the basic Doomsday argument, and I don’t have the time to discuss them all here. There is one particularly bizarre version, however, that I think merits a final word or two because is raises an interesting red herring. It’s called the “Shooting Room”.

Consider the following model for human existence. Souls are called into existence in groups representing each generation. The first generation has ten souls. The next has a hundred, the next after that a thousand, and so on. Each generation is led into a room, at the front of which is a pair of dice. The dice are rolled. If the score is double-six then everyone in the room is shot and it’s the end of humanity. If any other score is shown, everyone survives and is led out of the Shooting Room to be replaced by the next generation, which is ten times larger. The dice are rolled again, with the same rules. You find yourself called into existence and are led into the room along with the rest of your generation. What should you think is going to happen?

Leslie’s argument is the following. Each generation not only has more members than the previous one, but also contains more souls than have ever existed to that point. For example, the third generation has 1000 souls; the previous two had 10 and 100 respectively, i.e. 110 altogether. Roughly 90% of all humanity lives in the last generation. Whenever the last generation happens, there bound to be more people in that generation than in all generations up to that point. When you are called into existence you should therefore expect to be in the last generation. You should consequently expect that the dice will show double six and the celestial firing squad will take aim. On the other hand, if you think the dice are fair then each throw is independent of the previous one and a throw of double-six should have a probability of just one in thirty-six. On this basis, you should expect to survive. The odds are against the fatal score.

This apparent paradox seems to suggest that it matters a great deal whether the future is predetermined (your presence in the last generation requires the double-six to fall) or “random” (in which case there is the usual probability of a double-six). Leslie argues that if everything is pre-determined then we’re doomed. If there’s some indeterminism then we might survive. This isn’t really a paradox at all, simply an illustration of the fact that assuming different models gives rise to different probability assignments.

While I am on the subject of the Shooting Room, it is worth drawing a parallel with another classic puzzle of probability theory, the St Petersburg Paradox. This is an old chestnut to do with a purported winning strategy for Roulette. It was first proposed by Nicolas Bernoulli but famously discussed at greatest length by Daniel Bernoulli in the pages of Transactions of the St Petersburg Academy, hence the name. It works just as well for the case of a simple toss of a coin as for Roulette as in the latter game it involves betting only on red or black rather than on individual numbers.

Imagine you decide to bet such that you win by throwing heads. Your original stake is £1. If you win, the bank pays you at even money (i.e. you get your stake back plus another £1). If you lose, i.e. get tails, your strategy is to play again but bet double. If you win this time you get £4 back but have bet £2+£1=£3 up to that point. If you lose again you bet £8. If you win this time, you get £16 back but have paid in £8+£4+£2+£1=£15 to that point. Clearly, if you carry on the strategy of doubling your previous stake each time you lose, when you do eventually win you will be ahead by £1. It’s a guaranteed winner. Isn’t it?

The answer is yes, as long as you can guarantee that the number of losses you will suffer is finite. But in tosses of a fair coin there is no limit to the number of tails you can throw before getting a head. To get the correct probability of winning you have to allow for all possibilities. So what is your expected stake to win this £1? The answer is the root of the paradox. The probability that you win straight off is ½ (you need to throw a head), and your stake is £1 in this case so the contribution to the expectation is £0.50. The probability that you win on the second go is ¼ (you must lose the first time and win the second so it is ½ times ½) and your stake this time is £2 so this contributes the same £0.50 to the expectation. A moment’s thought tells you that each throw contributes the same amount, £0.50, to the expected stake. We have to add this up over all possibilities, and there are an infinite number of them. The result of summing them all up is therefore infinite. If you don’t believe this just think about how quickly your stake grows after only a few losses: £1, £2, £4, £8, £16, £32, £64, £128, £256, £512, £1024, etc. After only ten losses you are staking over a thousand pounds just to get your pound back. Sure, you can win £1 this way, but you need to expect to stake an infinite amount to guarantee doing so. It is not a very good way to get rich.

The relationship of all this to the Shooting Room is that it is shows it is dangerous to pre-suppose a finite value for a number which in principle could be infinite. If the number of souls that could be called into existence is allowed to be infinite, then any individual as no chance at all of being called into existence in any generation!

Amusing as they are, the thing that makes me most uncomfortable about these Doomsday arguments is that they attempt to determine a probability of an event without any reference to underlying mechanism. For me, a valid argument about Doomsday would have to involve a particular physical cause for the extinction of humanity (e.g. asteroid impact, climate change, nuclear war, etc). Given this physical mechanism one should construct a model within which one can estimate probabilities for the model parameters (such as the rate of occurrence of catastrophic asteroid impacts). Only then can one make a valid inference based on relevant observations and their associated likelihoods. Such calculations may indeed lead to alarming or depressing results. I fear that the greatest risk to our future survival is not from asteroid impact or global warming, where the chances can be estimated with reasonable precision, but self-destructive violence carried out by humans themselves. Science has no way of being able to predict what atrocities people are capable of so we can’t make any reliable estimate of the probability we will self-destruct. But the absence of any specific mechanism in the versions of the Doomsday argument I have discussed robs them of any scientific credibility at all.

There are better grounds for worrying about the future than mere numerology.

Galileo wasn’t as much of a mathematical genius as Newton, but he was highly imaginative, versatile and (very much unlike Newton) had an outgoing personality. He was also an able musician, fine artist and talented writer: in other words a true Renaissance man. His fame as a scientist largely depends on discoveries he made with the telescope. In particular, in 1610 he observed the four largest satellites of Jupiter, the phases of Venus and sunspots. He immediately leapt to the conclusion that not everything in the sky could be orbiting the Earth and openly promoted the Copernican view that the Sun was at the centre of the solar system with the planets orbiting around it. The Catholic Church was resistant to these ideas. He was hauled up in front of the Inquisition and placed under house arrest. He died in the year Newton was born (1642).

Galileo wasn’t as much of a mathematical genius as Newton, but he was highly imaginative, versatile and (very much unlike Newton) had an outgoing personality. He was also an able musician, fine artist and talented writer: in other words a true Renaissance man. His fame as a scientist largely depends on discoveries he made with the telescope. In particular, in 1610 he observed the four largest satellites of Jupiter, the phases of Venus and sunspots. He immediately leapt to the conclusion that not everything in the sky could be orbiting the Earth and openly promoted the Copernican view that the Sun was at the centre of the solar system with the planets orbiting around it. The Catholic Church was resistant to these ideas. He was hauled up in front of the Inquisition and placed under house arrest. He died in the year Newton was born (1642).

Karl Friedrich Gauss

Karl Friedrich Gauss  But the elder Jakob’s work on gambling clearly also had some effect on Daniel, as in 1735 the younger Bernoulli published an exceptionally clever study involving the application of probability theory to astronomy. It had been known for centuries that the orbits of the planets are confined to the same part in the sky as seen from Earth, a narrow band called the Zodiac. This is because the Earth and the planets orbit in approximately the same plane around the Sun. The Sun’s path in the sky as the Earth revolves also follows the Zodiac. We now know that the flattened shape of the Solar System holds clues to the processes by which it formed from a rotating cloud of cosmic debris that formed a disk from which the planets eventually condensed, but this idea was not well established in the time of Daniel Bernouilli. He set himself the challenge of figuring out what the chance was that the planets were orbiting in the same plane simply by chance, rather than because some physical processes confined them to the plane of a protoplanetary disk. His conclusion? The odds against the inclinations of the planetary orbits being aligned by chance were, well, astronomical.

But the elder Jakob’s work on gambling clearly also had some effect on Daniel, as in 1735 the younger Bernoulli published an exceptionally clever study involving the application of probability theory to astronomy. It had been known for centuries that the orbits of the planets are confined to the same part in the sky as seen from Earth, a narrow band called the Zodiac. This is because the Earth and the planets orbit in approximately the same plane around the Sun. The Sun’s path in the sky as the Earth revolves also follows the Zodiac. We now know that the flattened shape of the Solar System holds clues to the processes by which it formed from a rotating cloud of cosmic debris that formed a disk from which the planets eventually condensed, but this idea was not well established in the time of Daniel Bernouilli. He set himself the challenge of figuring out what the chance was that the planets were orbiting in the same plane simply by chance, rather than because some physical processes confined them to the plane of a protoplanetary disk. His conclusion? The odds against the inclinations of the planetary orbits being aligned by chance were, well, astronomical. It is impossible to overestimate the importance of the role played by

It is impossible to overestimate the importance of the role played by  A general proof of the Central Limit Theorem was finally furnished in 1838 by another astronomer,

A general proof of the Central Limit Theorem was finally furnished in 1838 by another astronomer,  Gambling in various forms has been around for millennia. Sumerian and Assyrian archaeological sites are littered with examples of a certain type of bone, called the astragalus (or talus bone). This is found just above the heel and its shape (in sheep and deer at any rate) is such that when it is tossed in the air it can land in any one of four possible orientations. It can therefore be used to generate “random” outcomes and is in many ways the forerunner of modern six-sided dice. The astragalus is known to have been used for gambling games as early as 3600 BC.

Gambling in various forms has been around for millennia. Sumerian and Assyrian archaeological sites are littered with examples of a certain type of bone, called the astragalus (or talus bone). This is found just above the heel and its shape (in sheep and deer at any rate) is such that when it is tossed in the air it can land in any one of four possible orientations. It can therefore be used to generate “random” outcomes and is in many ways the forerunner of modern six-sided dice. The astragalus is known to have been used for gambling games as early as 3600 BC.

I was watching an old episode of Sherlock Holmes last night – from the classic Granada TV series featuring Jeremy Brett’s brilliant (and splendidly camp) portrayal of the eponymous detective. One of the things that fascinates me about these and other detective stories is how often they use the word “deduction” to describe the logical methods involved in solving a crime.

I was watching an old episode of Sherlock Holmes last night – from the classic Granada TV series featuring Jeremy Brett’s brilliant (and splendidly camp) portrayal of the eponymous detective. One of the things that fascinates me about these and other detective stories is how often they use the word “deduction” to describe the logical methods involved in solving a crime.