Yesterday the Irish Government announced that there would be an additional Bank Holiday this year, on 18th March (which is the day after the existing St Patrick’s Day holiday on March 17th) to recognize the efforts of the great many people (including volunteers) who have worked so hard to counter the Covid-19 pandemic and to commemorate those who lost their lives to the coronavirus. It’s a good idea and hopefully it will occur at a time when there are many fewer restrictions than currently, which should make it a memorable occasion.

Interestingly, though, the new Bank Holiday is not a one-off but will become a permanent addition to the calendar, though on a different date: it will happen on or around 1st February from 2023 onwards. This is interesting because it corrects an anomaly in the distribution of public holidays, which I will explain here.

In the Northern hemisphere, from an astronomical point of view, the solar year is defined by the two solstices (summer, around June 21st, and winter, around December 21st) and the equinoxes (spring, around March 21st, and Autumn, around September 21st). These four events divide the year into four roughly equal parts of about 13 weeks each.

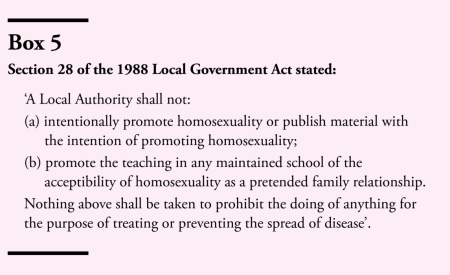

If you divide each of these intervals in two you divide the year into eight pieces of six and a bit weeks each. The dates midway between the astronomical events mentioned above are (roughly) :

- 1st February: Imbolc (Candlemas)

- 1st May: Beltane (Mayday)

- 1st August: Lughnasadh (Lammas)

- 1st November: Samhain (All Saints Day)

The names I’ve added in italics are taken from the Celtic/neo-Pagan and, in parenthesis the Christian terms),for these cross-quarter days. These timings are rough because the dates of the equinoxes and solstices vary from year to year. Imbolc is often taken to be the 2nd of February (Groundhog Day) and Samhain is sometimes taken to be October 31st, Halloween. But hopefully you get the point.

The last three of these also coincide closely with Bank Holidays in Ireland, though these are always on Mondays so may happen a few days away. I find it intriguing that the academic year for universities here in Ireland is largely defined by the above dates dates.

The first semester of the academic year 2021/22 started on September 20th 2021 (the Autumnal Equinox was on September 22nd) and finishes on 17th December (the Winter Solstice is on December 21st ). Halloween (31st October) was actually a Sunday this year so the related bank holiday was on Monday 25th October; half term (study week) always includes the Halloween Bank Holiday. The term was pushed forward a bit because it finished on a Friday and it would not be acceptable to end it on Christmas Eve!

After the break for Christmas, and a three-week mid-year exam period, Semester Two starts 31st January 2022. Half-term is then from 14th to 18th March (the Vernal Equinox; is on March 20th) and teaching ends on May 6th. More exams and end of year business take us to the Summer Solstice and the (hypothetical) vacation.

The new bank holiday will correct the anomaly that there has not been such a holiday to mark the first cross-quarter day (Imbolc). In Ireland this often referred to as St Brigid’s Day (after St Brigid of Kildare) rather than Candlemas.

The slight issue is that, in Maynooth, Semester Two of teaching usually begins around 1st February so there will be a holiday within a week or so of the start of teaching but I don’t imagine many students or staff will complain about that!

P.S. Imbolc is also sometimes called “The Quickening of the Year”. It looks like this year it will correspond to the quickening of relaxation of Covid-19 restrictions, though we still wait full details of what precisely all this means for our teaching plans…

Follow @telescoper