Thursday is Computational Physics Day this term so this morning I delivered the first Panopto lecture of that module and in the afternoon we had our first laboratory session. The students are all at home of course so we had to run the lab with them using their own laptops rather than the dedicated Linux cluster we have in the Department and interacting via Microsoft Teams. The first lab is very introductory so it was really just me presenting and them following on their machines without too much interaction. The ability to share a screen is actually very useful though and I imagine using it quite a lot to share Spyder. It went fairly well, I think, with all the students getting started out on the business of learning Python.

In between lecturing the morning and running the laboratory session this afternoon I had the chance to study another kind of language. Soon after I first arrived in Maynooth I got an email from Maynooth University about Irish language classes. Feeling a bit ashamed about not having learned Welsh in all my time in Cardiff, I thought I’d sign up for the Beginners class and fill in a Doodle Poll to help the organizers schedule it. Unfortunately, when the result was announced it was at a time that I couldn’t make owing to teaching, so I couldn’t do it. That happened a couple of times, in fact. This year however I’ve managed to register at a time I can make, though obviously the sessions are online.

I’m not sure how wise it is for me to try learning a new language during a term as busy as this, but I have to say I enjoyed the first session enormously. It was all very introductory, but I’ve learnt a few things about pronunciation – unsurprisingly the Irish word for pronunciation fuaimniú is unsurprisingly quite difficult to pronounce – and the difference between slender and broad vowels. I also learnt that to construct a verbal noun, instead of putting -ing on the end as you would in English, in Irish you use the word ag in front of the verb.

That’s not to say I had no problems. I’m still not sure I can say Dia duit (hello) properly. The second “d” is hardly pronounced.

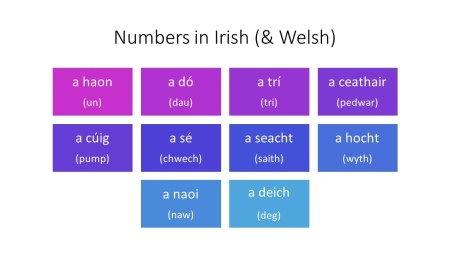

Irish isn’t much like Welsh, which I failed to learn previously. Although Irish and Welsh are both Celtic languages they are from two distinct groups: the Goidelic group that comprises Irish, Manx and Scottish Gaelic; and the Brythonic group that comprises Welsh, Cornish and Breton. These are sometimes referred to as q-Celtic and p-Celtic, respectively, although not everyone agrees that is a useful categorization. Incidentally, Scottish Gaelic is not the language spoken by the Celtic people who lived in Scotland at the time of the Romans, the Picts, which is lost. Scottish Gaelic is actually descended from Middle Irish. Also incidentally, Breton was taken to Brittany by a mass migration of people from South-West Britain fleeing the Anglo-Saxons which peaked somewhere around 500 AD. I guess that was the first Brexodus.

Welsh and Irish don’t sound at all similar to me, which is not surprising really. It is thought that the Brythonic languages evolved from a language brought to Britain by people from somewhere in Gaul (probably Northern France), whereas the people whose language led to the Goidelic tongues were probably from somewhere in the Iberia (modern-day Spain or Portugal). The modern versions of Irish and Welsh do contain words borrowed from Latin, French and English so there are similarities there too.

Only a diacritic mark appears in Irish, the síneadh fada (`long accent’), sometimes called the fada for short, which looks the same as the acute accent in, e.g., French. There’s actually one in síneadh if you look hard enough. It just means the vowel is pronounced long (i.e. the first syllable of síneadh is pronounced SHEEN). The word sean (meaning old) is pronounced like “shan” whereas Seán the name is pronounced “Shawn”.

One does find quite a few texts (especially online) where the fada is carelessly omitted, but it really is quite important. For example Cáca is the Irish word for `cake’, while the unaccented Caca means `excrement’…

I took the above text in Irish and English from the front cover of an old examination paper. You can see the accents as well as another feature of Irish which is slightly similar to Welsh, the mysterious lower-case h in front of Éireann. This is a consequence of an initial mutation, in which the initial character of word changes in various situations according to syntax or morphology (i.e. following certain words changing the case of a noun or following certain sounds). This specific case is an an example of h-prothesis (of an initial vowel).

In Welsh, mutations involve the substitution of one character for another. For example, `Wales’ is Cymru but if you cross the border into Wales you may see a sign saying Croeso i Gymru, the `C’ having mutated. The Irish language is a bit friendlier to the learner than Welsh, however, as the mutated character (h in the example above) is inserted in front of the unmutated character. Seeing both the mutated and unmutated character helps a person with limited vocabulary (such as myself) figure out what’s going on.

Mutations of consonants also occur in Irish. These can involve lenition (literally `weakening’, also known as aspiration) or eclipsis (nasalisation). In the case of eclipsis the unmutated consonant is preceded by another denoting the actual sound, e.g. b becomes m in terms of pronunciation, but what is written is mb. On the other hand, lenition is denoted by an h following the unmutated consonant. In older forms of Irish the overdot (ponc séimhithe) -another diacritic – was used to denote lenition.

Anyway, I’ve seen Dia duit written Dia dhuit which might explain why the d sounds so weak. We live and learn. If I keep at it long enough I might eventually be able to understand the TG4 commentary on the hurling..