And now, some poetry…

Archive for the Literature Category

Wine in a Can – Marcel Lucont

Posted in Poetry with tags Marcel Lucont, Poem, Wine in a Can on August 10, 2024 by telescoperA Physics Question

Posted in Literature, The Universe and Stuff on August 8, 2024 by telescoper

Is Shakespeare’s play Coriolanus different when performed in the Southern Hemisphere?

The Scale of Intensity – Don Paterson

Posted in Poetry with tags Don Paterson, Poem, Poetry, The Scale of Intensity on July 30, 2024 by telescoper1) Not felt. Smoke still rises vertically. In sensitive individuals, déjà vu, mild amnesia. Sea like a mirror.

2) Detected by persons at rest or favourably placed, i.e. in upper floors, hammocks, cathedrals, etc. Leaves rustle.

3) Light sleepers wake. Glasses chink. Hairpins, paperclips display slight magnetic properties. Irritability. Vibration like passing of light trucks.

4) Small bells ring. Small increase in surface tension and viscosity of certain liquids. Domestic violence. Furniture overturned.

5) Heavy sleepers wake. Public demonstrations. Large flags fly. Vibration like passing of heavy trucks.

6) Large bells ring. Bookburning. Aurora visible in daylight hours. Unprovoked assaults on strangers. Glassware broken. Loose tiles fly from roof.

7) Weak chimneys broken off at roofline. Waves on small ponds, water turbid with mud. Unprovoked assaults on neighbors. Large static charges built up on windows, mirrors, television screens.

8) Perceptible increase in weight of stationary objects: books, cups, pens heavy to lift. Fall of stucco and some masonry. Systemic rape of women and young girls. Sand craters. Cracks in wet ground.

9) Small trees uprooted. Bathwater drains in reverse vortex. Wholesale slaughter of religious and ethnic minorities. Conspicuous cracks in ground. Damage to reservoirs and underground pipelines.

10) Large trees uprooted. Measurable tide in puddles, teacups, etc. Torture and rape of small children. Irreparable damage to foundations. Rails bend. Sand shifts horizontally on beaches.

11) Standing impossible. Widespread self-mutilation. Corposant visible on pylons, lampposts, metal railings. Most bridges destroyed.

12) Damage total. Movement of hour hand perceptible. Large rack masses displaced. Sea white.

by Don Paterson (b. 1963)

Murder before Evensong by The Reverend Richard Coles

Posted in Literature, Television with tags Agatha Christie, book-review, Books, Caroline Graham, Detective Fiction, Midsomer Murders, Murder Before Evensong, mystery, Reverend Richard Coles on July 19, 2024 by telescoperThe Reverend Richard Coles (no relation), former Communard, ordained priest, broadcaster and TV celebrity recently turned his hand to writing murder mysteries. I bought his first crime novel, Murder Before Evensong, featuring Canon Daniel Clement, a couple of years ago but only got around to reading it recently. It caught my eye for two reasons, one that I am quite partial to whodunnits, and the other that I read and enjoyed the first volume of the author’s autobiography, Fathomless Riches, which showed him to be a very good writer.

As you might have guessed, Murder Before Evensong, is a kind of homage to the old-school Agatha Christie village murder typical of the Miss Marple stories. Murder at the Vicarage came immediately to mind when I first saw the book, but the story is not set so far in the past – more eighties than thirties. Richard Coles is also far wittier than Agatha Christie, with a definite touch of PG Wodehouse in his style. When I got into the book it reminded me very much of the original Midsomer Murders novels written by Caroline Graham, which I think are excellent; with somewhat whimsical plots, and populated with somewhat eccentric characters; the long-running TV series has long since run out of ideas, and is now tired and formulaic, but the books on which it is based are very good indeed. Like the original Inspector Barnaby stories, Murder Before Evensong is very funny in places, but less of a parody and more of an affectionate tribute to the genre. Coles also writes movingly about grief, and its effect on a close-knit rural community, no doubt informed by his own personal life and experiences as a parish priest. Canon Clement obviously has a lot of Richard Coles in him, including a love of dachsunds.

It’s difficult to review a murder mystery without giving a way the plot, so I’ll just say that it is well constructed. I narrowed the list of possibilities down to two very early on, and was proven right, but I didn’t really get the motive right.

Anyway, it’s an enjoyable read and recommended for enthusiasts. I gather that more Canon Clement stories are on the way. That reminds me of a line in an episode of Midsomer Murders, when Barnaby is joined by a new Detective Sergeant, just up from London, who is immediately plunged into the investigation of a killing spree. He turns to his Chief Inspector and says words to the effect of ‘For a small village there are a lot of murders around here’ to which Barnaby raises an eyebrow and says ‘Yes, that has been remarked upon…’

An Leabharlann

Posted in Biographical, History, Irish Language, Literature, Maynooth, Poetry with tags Books, Libraries, Maynooth, Maynooth Library on July 15, 2024 by telescoperAs I’ve mentioned before on this blog, over the past year or so I’ve been trying to catch up on my reading. My stack of books I’ve bought but never read is now down to half-a-dozen or so.

With sabbatical drawing to a close, the next major life even appearing on the horizon is retirement. Since that will involve a considerable reduction in income, and consequently money to buy books, and my house already has quite a lot of books in it, I thought I’d join the local public library so that when I’ve cleared the backlog of bought books, I’ll read books from the library instead.

With that in mind, I just joined the public library on Main Street, Maynooth, which is only about 15 minutes’ walk from my house. It’s a small branch library but is part of a larger network across County Kildare, with an extensive online catalogue from which one can acquire books on request. All this is free of charge.

Once I got my card, I had a quick look around the Maynooth branch. It has a good collection of classic literature (including poetry) as well as Irish and world history, which will keep me occupied for quite a while. The normal loan period is 3 weeks, which provides an incentive to read the book reasonably quickly.

I borrowed books in large quantities from public libraries when I was a child. I’m actually looking forward to getting into the library habit again.

Poppies in July Again

Posted in Biographical, Education, Maynooth, Poetry with tags Leaving Certificate, Poppies in July, Sylvia Plath on July 3, 2024 by telescoper

I just passed by some poppies growing on a rather scruffy piece of verge near my house. They reminded me of this poem by Sylvia Plath, which I have posted before.

Incidentally, this poem is among those of Sylvia Plath specified for the Leaving Certificate examination in English next year…

The Meaning of Everything by Simon Winchester

Posted in Biographical, History, Literature with tags English, English Language, etymology, language, Lexicography, Linguistics, OED, Oxford English Dictionary, Philology, Simon Winchester, The Meaning of Everything on May 12, 2024 by telescoperThe most recent item on my (non-research-related) sabbatical reading list to be completed is The Meaning of Everything by Simon Winchester, subtitled “The Story of the Oxford English Dictionary”. I didn’t actually buy this book, but won it in a crossword competition back in February 2019. It didn’t arrive in Ireland until the end of May 2019, so it has taken me a bit less than 5 years to read it. I wish I’d read it earlier as it is fascinating and very well-written.

There’s quite a lot of information about the Oxford English Dictionary on the wikipedia page so I will keep it brief here. In short, the idea of a definitive dictionary of the English language emanated from the Philological Society and dates back to 1857, but real work didn’t start on it until a decade later. The whole project was many times on the brink of cancellation because the task of compiling the dictionary turned out to be much greater than was imagined at the outset. It was thought that the dictionary would be finished in a few years, but the First Edition was not completed until 1928. I think most people imagine that the OED has been around much longer than that!

Almost immediately work began on a supplement to include words that had entered usage during the decades needed to compile the original. A complete Second Edition was published in 1989.

The OED was actually first published in fascicles, softbound publications of about 300 pages that could be later sewn into a hard binding. These were quite expensive – 12/6 each. The first, A-Ant, was published in 1884. A complete list of these can be found here.

One might imagine that the laborious nature of the work involved in compiling a dictionary of this sort would make the story rather dull but it’s actually fascinating, both to see how the task was approached and to learn about some of the characters involved. As well as the Editors – who were paid a salary – the work relied heavily on hundreds of volunteer readers who would scour the literature looking for useful quotations that revealed the meaning of a word. By “the literature” I mean anything written – novels, non-fiction, newspapers, magazines, technical papers, anything. These volunteers would send in apposite quotations from which the compilers would construct definitions of the words. Some “headwords” have many meanings – set is an extreme example, with over 430 senses – and others – such as back – appear in a large number of compound words, all of which it had been decided needed to be illustrated with a quotation. The First Edition contained over 400,000 words and nearly two million quotations, all written and indexed laboriously by hand.

Among the volunteer readers were some extraordinary characters. One such was William Chester Minor, an American former surgeon who worked tirelessly for the Dictionary, sending his contributions in the post from an address in Crowthorne, Berkshire, which happened to be Broadmoor Psychiatric Hospital. The Chief Editor of the OED, James Murray, apparently assumed that W.C. Minor worked at Broadmoor but in fact he had been committed there in 1878 because, overcome by some form of psychosis, he had murdered a stranger and deemed insane. Minor carried on his work – using the prison guards as assistants – until he became seriously ill in 1902 after another psychotic episode during which he cut off his own penis.

The real star of the show however is English itself and this book offers some fascinating insights into the origin and evolution of the language. Almost nothing of the Celtic languages spoken throughout England before the Roman conquest survives into Old English (which used to be called Anglo-Saxon). This had a lexicon of around 50,000 words but only a few thousand of these survived in any form into Middle English and Modern English. Many common words in Old English were replaced and the language otherwise altered dramatically due to an influx of words, first from Scandinavia, via the Vikings, then from Norman French, and later on from diverse languages around the world. English has steadily absorbed and incorporated words from other languages for centuries, and is still doing so, though these words sometimes have a meaning in English that differs from their original.

In the light of this dramatic evolution in the language the Oxford English Dictionary was never intended to legislate on usage, but to register it; this is why its lexicographers relied so much on quotations in forming their definitions. This is also why the OED will never really be finished. The task of updating it nowadays is, on the one hand, made easier by the availability of computers and searchable databases but, on the other, made more difficult by the sheer amount of literature being produced.

I’ll send with one of the (apparently inadvertent) funny bits in the OED, from the second definition of the rarely used noun abbreviator:

An officer of the court of Rome, appointed… to draw up the Pope’s briefs…

I say it is inadvertent because the OED gives the earliest usage of the word briefs meaning underwear as 1930, after the publication of the First Edition (in which this appears).

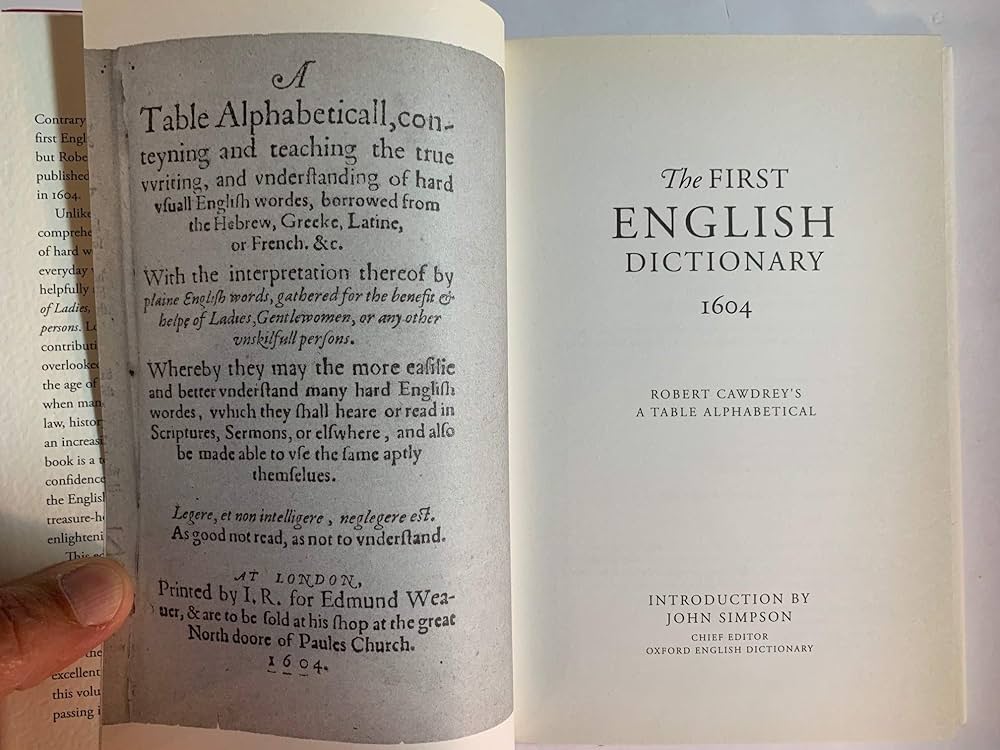

A Table Alphabeticall

Posted in History, Literature with tags A Table Alphabeticall, Dictionary, English Language, Robert Cawdrey on May 5, 2024 by telescoperI’m having a lazy Sunday so instead of writing anything too demanding on here I thought I’d share something I stumbled across in a book I’ve been reading (and will probably review next week sometime). Not a lot of people know that the first true English dictionary was called A Table Alphabeticall which was created by Robert Cawdrey and first published in London in 1604, over 150 years before Samuel Johnson’s much more famous A Dictionary of the English Language.

This, on the left, is the frontispiece of the First Edition to A Table Alphabeticall:

Notice that it says it was compiled for the benefit and help of “Ladies, Gentlewomen, or any other unskilfull persons”. Ouch! By the Third Edition, published in 1613, this was amended to “all unskilfull persons”.

P.S. Notice the old-fashioned typesetting, especially the use of the “long s” which I have blogged about before.

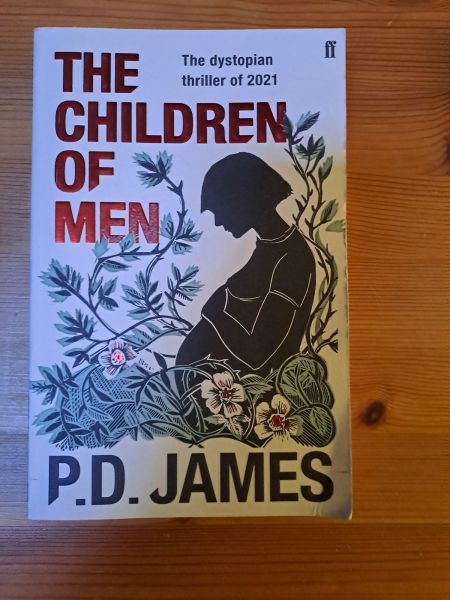

The Children of Men by P.D. James

Posted in Biographical, Literature with tags Book, book-review, Books, Dystopia, fiction, Novel, P.D. James, The Children of Men on April 28, 2024 by telescoperWhen I finished reading Death Comes to Pemberley by P.D. James I realized that there was one other book by the same author that I had never read, the dystopian thriller The Children of Men. I bought the above edition about five years ago, but the novel was first published in 1992.

The premise of this story, set in the (then future) 2021 is that, in 1995, for reasons unknown, the entire human race suddenly lost the ability to reproduce. The book makes no attempt to explain the origins of this mass infertility, and it is a conceit that I found very implausible, but I did manage to suspend my disbelief enough to engage with the author’s ideas about what a society without children might be like. That is basically what the first half of the book tries to do. It’s an interesting idea and what develops is not the kind of post-apocalyptic scenario that has been written about many times before.

In 2021 England is ruled by a dictator, called the Warden, by the name of Xan. He happens to be the cousin of the principal protagonist, Theo. The Powers That Be introduce the concept of a Quietus, at which elderly people are forced to commit mass suicide. A penal colony is set up on the Isle of Man where prisoners are dumped and left to fend for themselves. As the population ages, schools and colleges close, buildings are left to decay, and as numbers decrease people are forced to move to larger towns, the only places where services and utilities can be maintained.

One thing that struck me reading this in 2024 is that the author did not foresee any of the technological advances that were to occur between 1995 and 201. The existence of the internet or even mobile phones would have had significant implications for the plot.

The novel is split into two parts, Book 1 (Omega) and Book 2 (Alpha), and the first part is largely devoted to describing the decay and hopelessness of a society without children. I found it rather heavy-handed, with too much sermonizing. While Book 1 verges on a sort of allegory, no doubt inspired by the author’s own Christian faith, n Book 2 the story becomes a well-plotted thriller. After witnessing the horror of a Quietus, Theo joins a small group of dissidents based in Oxford who carry out a campaign to disrupt such events and think that Theo’s relationship to the Warden might be useful in effecting change at the top. As well as being Xan’s cousin, Theo used to work for Government as an adviser to the Warden.

The group is, however, rumbled and its members have to flee into the countryside. Along the way we find that one of their number, a woman by the name of Julian, is pregnant. Fortunately another member of the group, Miriam, is a midwife (although she obviously hasn’t practiced for 25 years). We learn the identify of the father of Julian’s child but not the reason why she has conceived when apparently nobody else on the planet can. Obviously the Alpha in the title of the second book refers to this child. I won’t say how it all finishes, except that the ending is ambiguous.

The fugitives-on-the-run part of the story in Book 2 is very well crafted and genuinely exciting, but the pregnancy adds yet another level of implausibility to a plot that seemed to me already very contrived. Although it is a page-turner I found it ultimately unsatisfying.

P.S. I understand there is a film based on the book, but I haven’t seen it.