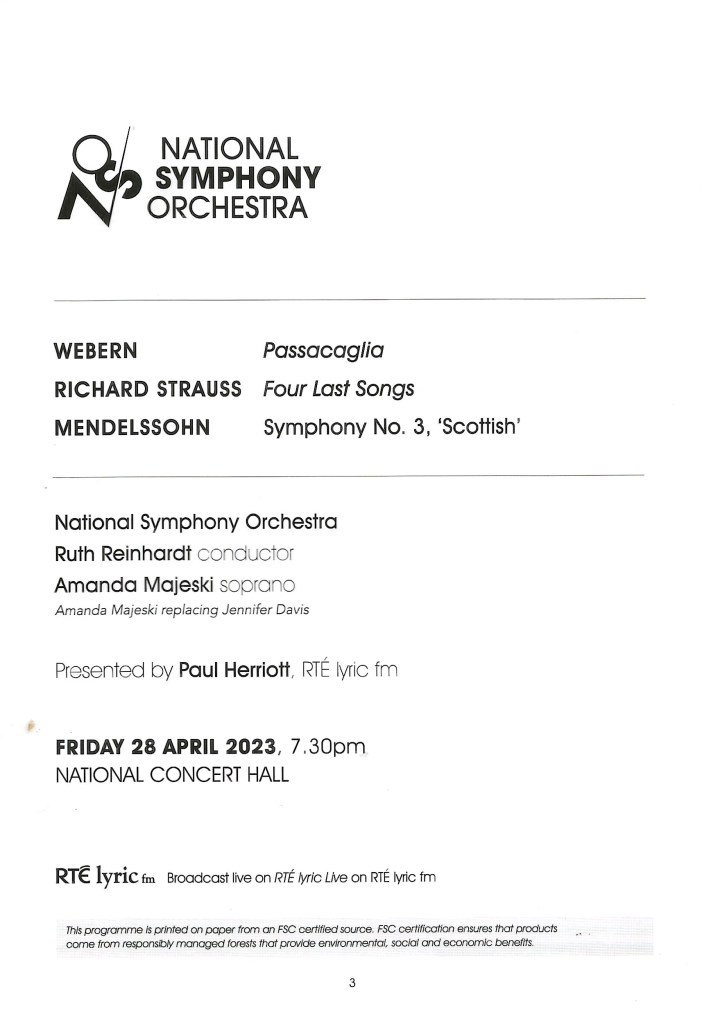

Last night I went to the National Concert Hall in Dublin for the penultimate performance of the season by the National Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Christian Reif, for a programme of music by Benjamin Britten, Grażyna Bacewicz and Sergei Prokofiev all written in the 1940s. The hall was not even half full for this concert, which is a shame because it was both interesting and enjoyable, but at least it was broadcast live so it could be heard on the radio.

I’d never heard Britten’s Les Illuminations in a live performance before last night, although I had heard it on BBC Radio 3 some time ago. It’s a cycle of nine songs based on poems by Arthur Rimbaud, including an opening ‘fanfare’ and interlude based on a single phrase of Rimbaud J’ai seul la clef de sette parade sauvage. The themes of the text are the poet’s reactions to desire, exile, transgression and decadence. Britten apparently felt more comfortable setting these themes, and conveying the sense of homoerotic desire that pervades the poems, in French because he felt that he could use them to say things he couldn’t say in English. Even so, he did omit some of the naughtier bits of Rimbaud’s texts.

Britten started writing Les Illuminations in 1939 but finished it after he had moved to America and it was first performed in 1940. This was an early “hit” for Britten and I found Julia Bullock‘s lovely soprano voice give it a very different form of sensuality than it has when performed by a tenor; it was performed quite often by Peter Pears, actually. Incidentally, Julia Bullock is married to conductor Christian Reif.

Next up was a work that was completely new to me, the Concerto for String Orchestra by Grażyna Bacewicz which was written in 1948. In three movements, this is rather like an old-fashioned Concerto Grosso in construction, but with a distinctively modern edge. The outer movements are forceful and energetic, contrasting with a beautiful but rather desolate Andante in the middle. I’m glad to have been introduced to this work and indeed to this composer. I must find out more about her.

The first two pieces featured only the strings of the National Symphony Orchestra but after the win break the stage was joined by the brass, woodwinds, and a full panoply of percussion (including a piano) for Symphony No. 5 in B♭ Major, which he wrote in the summer of 1944 and was first performed in January 1945 with Prokofiev himself conducting. This work is generally perceived to be an expression of the anticipation of victory over the Nazis after the opening up of the Western front by the Normandy landings. According to the programme, however, the composer had been sketching the symphony for several years beforehand, so this can’t all be true. I think you can read it in two ways, one as the devastating human cost of the war with Russia and the other as a covert response to Soviet oppression. Prokofiev, like Shostakovich, was good at ambiguity. I guess he had to be.

In four movements, this Symphony opens with an expansive Andante movement, followed by and Allegro which is rather like a Scherzo, a darkly beautiful Adagio, and a very varied final Allegro. I found myself at times thinking of Prokofiev’s music for the film Alexander Nevsky and the menacing atmosphere of the ballet Romeo and Juliet.

The winds and percussion had obviously been champing at the bit during the first half, and they unleashed some terrific playing during this performance, especially during the climactic passages that evoke thunderstorms or battles. Whatever they are intended to represent, if anything, I enjoyed the loud bits very much.

Congratulations to the National Symphony Orchestra and soloist Julia Bullock on an excellent evening of music. I do enjoy being introduced to unfamiliar works and do love the site and sound of a big orchestra in full flood. I look forward to next week’s concert, the Season Finale.