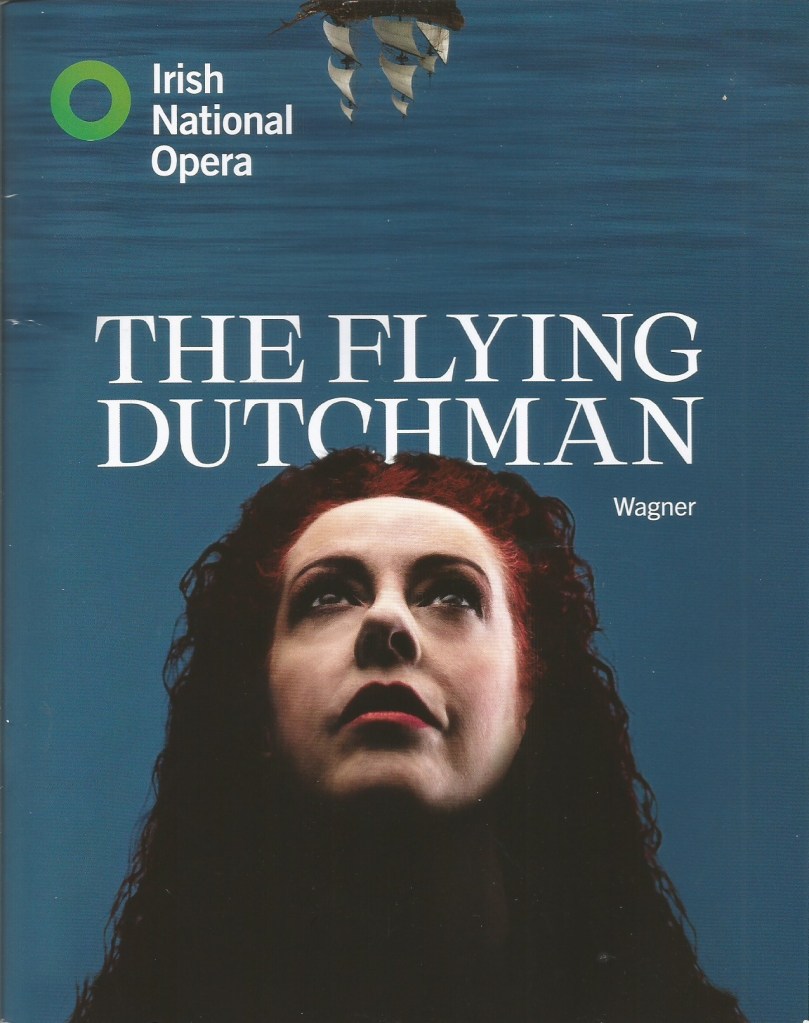

And so it came to pass that this afternoon I took the bus into Dublin to catch the first performance of Irish National Opera’s new production of Richard Wagner‘s The Flying Dutchman (or Der fliegende Holländer to give its proper title) at the romantically named Bord Gáis (Gas Board) Energy Theatre. It wasn’t exactly the first night, as the performance started at 5pm, but it did have a first night feel to it, with a smattering of media types in the full house.

The event took a bizarre twist at the interval, which was after Act 1. I’d only just collected my glass of wine when the fire alarm went off and we were told to leave the building. Amusingly, some of the cast joined us outside too, in costume. It was a false alarm, but the precautionary exodus extended the interval by about 15 minutes or so. When we were making our way back in, I overheard a nearby wit say “Never mind: worse things happen at sea”. Given the plot of the opera, that seemed a very apt comment.

The Flying Dutchman is an early composition by Wagner, first performed in 1843 when Wagner was only 30 years old. It’s much more of a conventional opera than his later music dramas. At least to my ears there are passages that sound a lot like Verdi, especially those featuring the chorus. It’s also quite short: it’s often performed without an interval, but even with one (and a fire alarm to boot) it’s only about three hours. On the other hand, there are some manifestations of things to come, especially the frequent use of a leitmotif whenever the eponymous Dutchman appears or is mentioned.

The story is set somewhere on the coast of Norway. This production has an intriguing preamble while the famous overture is playing. While the menfolk are away at sea, the women of a coastal village are going about their business. Among them is a little girl in a striking red coat. Shades of Schindler’s List, I thought. The little girl turns out to be “Little Senta”, a representation of the innocence of Senta, the leading female character.

The opera proper begings on a ship captained by a man called Daland which has been driven off course by a storm and is sheltering at anchor. While the crew are taking some rest, another ship appears beside and The Dutchman climbs onto Daland’s ship to have a look around. He meets Daland, explains that he is exiled from Holland, is fed up with travelling the seas all alone. He showers Daland with gifts and asks if he can marry Daland’s daughter, Senta. Daland is very keen to have a rich son-in-law and speedily gives his consent.

Meanwhile, back onshore, we’re in Act II. Senta is revealed to be obsessed with a portrait of the Flying Dutchman, a man cursed to wander the oceans until he finds a woman prepared to be completely faithful to him. She has known about this legendary figure since she was a child and wants to be the person who saves him from his fate. One person not happy about this is Erik, an impoverished hunter who himself wants to marry Senta. Eventually Daland’s and the Dutchman’s ships come home. Senta is overwhelmed to meet the Dutchman in person and consents to marry him.

Act III begins with a big party at which the sailor’s on Daland’s ship get drunk and try to get the crew of the Dutchman’s ship to reveal themselves, initially to no avail because they are ghosts. When they do appear it’s not a pretty sight. Erik comes back and tries to convince Senta to stay with him instead of mmarrying the Dutchman. The Dutchman overhears them and interprets their discussion as a betrayal in progress. He tells Senta to forget the whole thing and jumps on board his ship which descends into the sea. Heartbroken, Senta throws herself into the water after him, and drowns.

In the closing stages, Senta has changed is wearing a striking red coat just like Little Senta wore at the beginning. When Senta dies, Little Senta’s lifeless body appears suspended from a rope in the middle of the stage, symbolising her sacrifice and shattered dreams.

In a very strong cast, James Cresswell (bass) was an outstanding Daland, but others were fine too: Gavan Ring (tenor) was The Steersman, Jordan Shanahan (baritone) The Dutchman, Carolyn Dobbin (mezzo) Mary, Giselle Allen (soprano) Senta, Toby Spence (tenor) Erik and the non-singing part of Little Senta was engagingly played by Caroline Wheeler. The Orchestra and Chorus of Irish National Opera were also in fine form.

The set design by Francis O’Connor was relatively simple but highly effective: the only significant change after Act I (see picture above) was the wheelhouse to the right was removed and a lighthouse placed further towards the rear, from which Senta took her plunge at the end. There was some dramatic use of animated back-projections too.

This is the first time I’ve seen this opera. I was very impressed with the performance, both musically and dramatically. If anyone is thinking of trying their first taste of Wagner then they could do much worse than this production, but they’ll have to hurry – there are just three more performances in Dublin (Tuesday 25th, Thursday 27th and Saturday 29th March).

P.S. I usually go by train into Dublin for concerts and other performances, but there are two buses that go all the way from Maynooth to the Grand Canal Quay, which is where the Bord Gáis Energy Theatre is located so I thought I’d try them out. I took a C4 in and a C3 home, both journeys being pleasantly uneventful.