It seems the little poll about cosmic inflation I posted last week with humorous intent has ruffled a few feathers, but at least it gives me the excuse to wheel out an updated and edited version of an old piece I wrote on the subject.

Just over thirty years ago a young physicist came up with what seemed at first to be an absurd idea: that, for a brief moment in the very distant past, just after the Big Bang, something weird happened to gravity that made it push rather than pull. During this time the Universe went through an ultra-short episode of ultra-fast expansion. The physicist in question, Alan Guth, couldn’t prove that this “inflation” had happened nor could he suggest a compelling physical reason why it should, but the idea seemed nevertheless to solve several major problems in cosmology.

Three decades later, Guth is a professor at MIT and inflation is now well established as an essential component of the standard model of cosmology. But should it be? After all, we still don’t know what caused it and there is little direct evidence that it actually took place. Data from probes of the cosmic microwave background seem to be consistent with the idea that inflation happened, but how confident can we be that it is really a part of the Universe’s history?

a professor at MIT and inflation is now well established as an essential component of the standard model of cosmology. But should it be? After all, we still don’t know what caused it and there is little direct evidence that it actually took place. Data from probes of the cosmic microwave background seem to be consistent with the idea that inflation happened, but how confident can we be that it is really a part of the Universe’s history?

According to the Big Bang theory, the Universe was born in a dense fireball which has been expanding and cooling for about 14 billion years. The basic elements of this theory have been in place for over eighty years, but it is only in the last decade or so that a detailed model has been constructed which fits most of the available observations with reasonable precision. The problem is that the Big Bang model is seriously incomplete. The fact that we do not understand the nature of the dark matter and dark energy that appears to fill the Universe is a serious shortcoming. Even worse, we have no way at all of describing the very beginning of the Universe, which appears in the equations used by cosmologists as a “singularity”- a point of infinite density that defies any sensible theoretical calculation. We have no way to define a priori the initial conditions that determine the subsequent evolution of the Big Bang, so we have to try to infer from observations, rather than deduce by theory, the parameters that govern it.

The establishment of the new standard model (known in the trade as the “concordance” cosmology) is now allowing astrophysicists to turn back the clock in order to understand the very early stages of the Universe’s history and hopefully to understand the answer to the ultimate question of what happened at the Big Bang itself and thus answer the question “How did the Universe Begin?”

Paradoxically, it is observations on the largest scales accessible to technology that provide the best clues about the earliest stages of cosmic evolution. In effect, the Universe acts like a microscope: primordial structures smaller than atoms are blown up to astronomical scales by the expansion of the Universe. This also allows particle physicists to use cosmological observations to probe structures too small to be resolved in laboratory experiments.

Our ability to reconstruct the history of our Universe, or at least to attempt this feat, depends on the fact that light travels with a finite speed. The further away we see a light source, the further back in time its light was emitted. We can now observe light from stars in distant galaxies emitted when the Universe was less than one-sixth of its current size. In fact we can see even further back than this using microwave radiation rather than optical light. Our Universe is bathed in a faint glow of microwaves produced when it was about one-thousandth of its current size and had a temperature of thousands of degrees, rather than the chilly three degrees above absolute zero that characterizes the present-day Universe. The existence of this cosmic background radiation is one of the key pieces of evidence in favour of the Big Bang model; it was first detected in 1964 by Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson who subsequently won the Nobel Prize for their discovery.

The process by which the standard cosmological model was assembled has been a gradual one, but the latest step was taken by the European Space Agency’s Planck mission . I’ve blogged about the implications of the Planck results for cosmic inflation in more technical detail here. In a nutshell, for several years this satellite mapped the properties of the cosmic microwave background and how it varies across the sky. Small variations in the temperature of the sky result from sound waves excited in the hot plasma of the primordial fireball. These have characteristic properties that allow us to probe the early Universe in much the same way that solar astronomers use observations of the surface of the Sun to understand its inner structure, a technique known as helioseismology. The detection of the primaeval sound waves is one of the triumphs of modern cosmology, not least because their amplitude tells us precisely how loud the Big Bang really was.

The pattern of fluctuations in the cosmic radiation also allows us to probe one of the exciting predictions of Einstein’s general theory of relativity: that space should be curved by the presence of matter or energy. Measurements from Planck and its predecessor WMAP reveal that our Universe is very special: it has very little curvature, and so has a very finely balanced energy budget: the positive energy of the expansion almost exactly cancels the negative energy relating of gravitational attraction. The Universe is (very nearly) flat.

The observed geometry of the Universe provides a strong piece of evidence that there is an mysterious and overwhelming preponderance of dark stuff in our Universe. We can’t see this dark matter and dark energy directly, but we know it must be there because we know the overall budget is balanced. If only economics were as simple as physics.

Computer Simulation of the Cosmic Web

The concordance cosmology has been constructed not only from observations of the cosmic microwave background, but also using hints supplied by observations of distant supernovae and by the so-called “cosmic web” – the pattern seen in the large-scale distribution of galaxies which appears to match the properties calculated from computer simulations like the one shown above, courtesy of Volker Springel. The picture that has emerged to account for these disparate clues is consistent with the idea that the Universe is dominated by a blend of dark energy and dark matter, and in which the early stages of cosmic evolution involved an episode of accelerated expansion called inflation.

A quarter of a century ago, our understanding of the state of the Universe was much less precise than today’s concordance cosmology. In those days it was a domain in which theoretical speculation dominated over measurement and observation. Available technology simply wasn’t up to the task of performing large-scale galaxy surveys or detecting slight ripples in the cosmic microwave background. The lack of stringent experimental constraints made cosmology a theorists’ paradise in which many imaginative and esoteric ideas blossomed. Not all of these survived to be included in the concordance model, but inflation proved to be one of the hardiest (and indeed most beautiful) flowers in the cosmological garden.

Although some of the concepts involved had been formulated in the 1970s by Alexei Starobinsky, it was Alan Guth who in 1981 produced the paper in which the inflationary Universe picture first crystallized. At this time cosmologists didn’t know that the Universe was as flat as we now think it to be, but it was still a puzzle to understand why it was even anywhere near flat. There was no particular reason why the Universe should not be extremely curved. After all, the great theoretical breakthrough of Einstein’s general theory of relativity was the realization that space could be curved. Wasn’t it a bit strange that after all the effort needed to establish the connection between energy and curvature, our Universe decided to be flat? Of all the possible initial conditions for the Universe, isn’t this very improbable? As well as being nearly flat, our Universe is also astonishingly smooth. Although it contains galaxies that cluster into immense chains over a hundred million light years long, on scales of billions of light years it is almost featureless. This also seems surprising. Why is the celestial tablecloth so immaculately ironed?

Guth grappled with these questions and realized that they could be resolved rather elegantly if only the force of gravity could be persuaded to change its sign for a very short time just after the Big Bang. If gravity could push rather than pull, then the expansion of the Universe could speed up rather than slow down. Then the Universe could inflate by an enormous factor (1060 or more) in next to no time and, even if it were initially curved and wrinkled, all memory of this messy starting configuration would be lost. Our present-day Universe would be very flat and very smooth no matter how it had started out.

But how could this bizarre period of anti-gravity be realized? Guth hit upon a simple physical mechanism by which inflation might just work in practice. It relied on the fact that in the extreme conditions pertaining just after the Big Bang, matter does not behave according to the classical laws describing gases and liquids but instead must be described by quantum field theory. The simplest type of quantum field is called a scalar field; such objects are associated with particles that have no spin. Modern particle theory involves many scalar fields which are not observed in low-energy interactions, but which may well dominate affairs at the extreme energies of the primordial fireball.

Classical fluids can undergo what is called a phase transition if they are heated or cooled. Water for example, exists in the form of steam at high temperature but it condenses into a liquid as it cools. A similar thing happens with scalar fields: their configuration is expected to change as the Universe expands and cools. Phase transitions do not happen instantaneously, however, and sometimes the substance involved gets trapped in an uncomfortable state in between where it was and where it wants to be. Guth realized that if a scalar field got stuck in such a “false” state, energy – in a form known as vacuum energy – could become available to drive the Universe into accelerated expansion.We don’t know which scalar field of the many that may exist theoretically is responsible for generating inflation, but whatever it is, it is now dubbed the inflaton.

This mechanism is an echo of a much earlier idea introduced to the world of cosmology by Albert Einstein in 1916. He didn’t use the term vacuum energy; he called it a cosmological constant. He also didn’t imagine that it arose from quantum fields but considered it to be a modification of the law of gravity. Nevertheless, Einstein’s cosmological constant idea was incorporated by Willem de Sitter into a theoretical model of an accelerating Universe. This is essentially the same mathematics that is used in modern inflationary cosmology. The connection between scalar fields and the cosmological constant may also eventually explain why our Universe seems to be accelerating now, but that would require a scalar field with a much lower effective energy scale than that required to drive inflation. Perhaps dark energy is some kind of shadow of the inflaton

Guth wasn’t the sole creator of inflation. Andy Albrecht and Paul Steinhardt, Andrei Linde, Alexei Starobinsky, and many others, produced different and, in some cases, more compelling variations on the basic theme. It was almost as if it was an idea whose time had come. Suddenly inflation was an indispensable part of cosmological theory. Literally hundreds of versions of it appeared in the leading scientific journals: old inflation, new inflation, chaotic inflation, extended inflation, and so on. Out of this activity came the realization that a phase transition as such wasn’t really necessary, all that mattered was that the field should find itself in a configuration where the vacuum energy dominated. It was also realized that other theories not involving scalar fields could behave as if they did. Modified gravity theories or theories with extra space-time dimensions provide ways of mimicking scalar fields with rather different physics. And if inflation could work with one scalar field, why not have inflation with two or more? The only problem was that there wasn’t a shred of evidence that inflation had actually happened.

This episode provides a fascinating glimpse into the historical and sociological development of cosmology in the eighties and nineties. Inflation is undoubtedly a beautiful idea. But the problems it solves were theoretical problems, not observational ones. For example, the apparent fine-tuning of the flatness of the Universe can be traced back to the absence of a theory of initial conditions for the Universe. Inflation turns an initially curved universe into a flat one, but the fact that the Universe appears to be flat doesn’t prove that inflation happened. There are initial conditions that lead to present-day flatness even without the intervention of an inflationary epoch. One might argue that these are special and therefore “improbable”, and consequently that it is more probable that inflation happened than that it didn’t. But on the other hand, without a proper theory of the initial conditions, how can we say which are more probable? Based on this kind of argument alone, we would probably never really know whether we live in an inflationary Universe or not.

But there is another thread in the story of inflation that makes it much more compelling as a scientific theory because it makes direct contact with observations. Although it was not the original motivation for the idea, Guth and others realized very early on that if a scalar field were responsible for inflation then it should be governed by the usual rules governing quantum fields. One of the things that quantum physics tells us is that nothing evolves entirely smoothly. Heisenberg’s famous Uncertainty Principle imposes a degree of unpredictability of the behaviour of the inflaton. The most important ramification of this is that although inflation smooths away any primordial wrinkles in the fabric of space-time, in the process it lays down others of its own. The inflationary wrinkles are really ripples, and are caused by wave-like fluctuations in the density of matter travelling through the Universe like sound waves travelling through air. Without these fluctuations the cosmos would be smooth and featureless, containing no variations in density or pressure and therefore no sound waves. Even if it began in a fireball, such a Universe would be silent. Inflation puts the Bang in Big Bang.

The acoustic oscillations generated by inflation have a broad spectrum (they comprise oscillations with a wide range of wavelengths), they are of small amplitude (about one hundred thousandth of the background); they are spatially random and have Gaussian statistics (like waves on the surface of the sea; this is the most disordered state); they are adiabatic (matter and radiation fluctuate together) and they are formed coherently. This last point is perhaps the most important. Because inflation happens so rapidly all of the acoustic “modes” are excited at the same time. Hitting a metal pipe with a hammer generates a wide range of sound frequencies, but all the different modes of the start their oscillations at the same time. The result is not just random noise but something moderately tuneful. The Big Bang wasn’t exactly melodic, but there is a discernible relic of the coherent nature of the sound waves in the pattern of cosmic microwave temperature fluctuations seen in the Cosmic Microwave Background. The acoustic peaks seen in the Planck angular spectrum provide compelling evidence that whatever generated the pattern did so coherently.

There are very few alternative theories on the table that are capable of reproducing these results, but does this mean that inflation really happened? Do they “prove” inflation is correct? More generally, is the idea of inflation even testable?

So did inflation really happen? Does Planck prove it? Will we ever know?

It is difficult to talk sensibly about scientific proof of phenomena that are so far removed from everyday experience. At what level can we prove anything in astronomy, even on the relatively small scale of the Solar System? We all accept that the Earth goes around the Sun, but do we really even know for sure that the Universe is expanding? I would say that the latter hypothesis has survived so many tests and is consistent with so many other aspects of cosmology that it has become, for pragmatic reasons, an indispensable part our world view. I would hesitate, though, to say that it was proven beyond all reasonable doubt. The same goes for inflation. It is a beautiful idea that fits snugly within the standard cosmological and binds many parts of it together. But that doesn’t necessarily make it true. Many theories are beautiful, but that is not sufficient to prove them right.

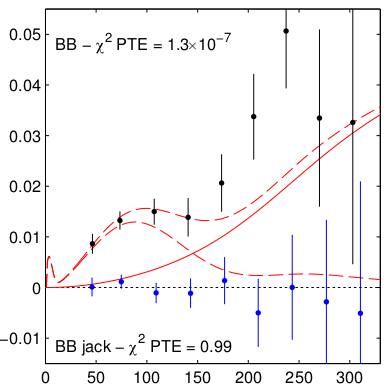

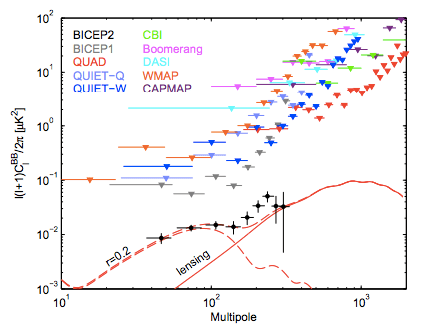

When generating theoretical ideas scientists should be fearlessly radical, but when it comes to interpreting evidence we should all be unflinchingly conservative. The Planck measurements have also provided a tantalizing glimpse into the future of cosmology, and yet more stringent tests of the standard framework that currently underpins it. Primordial fluctuations produce not only a pattern of temperature variations over the sky, but also a corresponding pattern of polarization. This is fiendishly difficult to measure, partly because it is such a weak signal (only a few percent of the temperature signal) and partly because the primordial microwaves are heavily polluted by polarized radiation from our own Galaxy. Polarization data from Planck are yet to be released; the fiendish data analysis challenge involved is the reason for the delay. But there is a crucial target that justifies these endeavours. Inflation does not just produce acoustic waves, it also generates different modes of fluctuation, called gravitational waves, that involve twisting deformations of space-time. Inflationary models connect the properties of acoustic and gravitational fluctuations so if the latter can be detected the implications for the theory are profound. Gravitational waves produce very particular form of polarization pattern (called the B-mode) which can’t be generated by acoustic waves so this seems a promising way to test inflation. Unfortunately the B-mode signal is expected to be very weak and the experience of WMAP suggests it might be swamped by foregrounds. But it is definitely worth a go, because it would add considerably to the evidence in favour of inflation as an element of physical reality.

But would even detection of primordial gravitational waves really test inflation? Not really. The problem with inflation is that it is a name given to a very general idea, and there are many (perhaps infinitely many) different ways of implementing the details, so one can devise versions of the inflationary scenario that produce a wide range of outcomes. It is therefore unlikely that there will be a magic bullet that will kill inflation dead. What is more likely is a gradual process of reducing the theoretical slack as much as possible with observational data, such as is happening in particle physics. For example, we have not yet identified the inflaton field (nor indeed any reasonable candidate for it) but we are gradually improving constraints on the allowed parameter space. Progress in this mode of science is evolutionary not revolutionary.

Many critics of inflation argue that it is not a scientific theory because it is not falsifiable. I don’t think falsifiability is a useful concept in this context; see my many posts relating to Karl Popper. Testability is a more appropriate criterion. What matters is that we have a systematic way of deciding which of a set of competing models is the best when it comes to confrontation with data. In the case of inflation we simply don’t have a compelling model to test it against. For the time being therefore, like it or not, cosmic inflation is clearly the best model we have. Maybe someday a worthy challenger will enter the arena, but this has not happened yet.

Most working cosmologists are as aware of the difficulty of testing inflation as they are of its elegance. There are also those who talk as if inflation were an absolute truth, and those who assert that it is not a proper scientific theory (because it isn’t falsifiable). I can’t agree with either of these factions. The truth is that we don’t know how the Universe really began; we just work on the best ideas available and try to reduce our level of ignorance in any way we can. We can hardly expect the secrets of the Universe to be so easily accessible to our little monkey brains.

a professor at MIT and inflation is now well established as an essential component of the standard model of cosmology. But should it be? After all, we still don’t know what caused it and there is little direct evidence that it actually took place. Data from probes of the cosmic microwave background seem to be consistent with the idea that inflation happened, but how confident can we be that it is really a part of the Universe’s history?

a professor at MIT and inflation is now well established as an essential component of the standard model of cosmology. But should it be? After all, we still don’t know what caused it and there is little direct evidence that it actually took place. Data from probes of the cosmic microwave background seem to be consistent with the idea that inflation happened, but how confident can we be that it is really a part of the Universe’s history?