Yesterday (17th April) was the last day of our Easter vacation – back to the grind on Monday – and it was also the occasion of a special meeting to mark the retirement of Professor Leonid Petrovich Grishchuk.

Leonid has been a Distinguished Research Professor here in Cardiff since 1995. You can read more of his scientific biography and wider achievements here, but it should suffice to say that he is a pioneer of many aspects of relativistic cosmology and particularly primordial gravitational waves. He’s also a larger-than-life character who is known with great affection around the world.

Among other things, he’s a big fan of football. He still plays, as a matter of fact, although he generally spends more time ordering his team-mates about than actually running around himself. One of his retirement presents was a Cardiff City football shirt with his name on the back.

My first experience of Leonid was many years ago at a scientific meeting at which I attempted to give a talk. Leonid was in the audience and he interrupted me, rather aggressively. I didn’t really understand his question so he had another go at me in the questions afterwards. I don’t mind admitting that I was quite upset with his behaviour. I think a large fraction of working cosmologists have probably been Grischchucked at one time or another.

Later on, though, people from the meeting were congregating at a bar when he arrived and headed for me. I didn’t really want to talk to him as I felt he had been quite rude. However, there wasn’t really any way of escaping so I ended up talking to him over a beer. We finally resolved the question he had been trying to ask me and his demeanour changed completely. We spent the rest of the evening having dinner and talking about all sorts of things and have been friends ever since.

Over the years I’ve learned that this is very much a tradition amongst Russian scientists of the older school. They can seem very hostile – even brutal – when discussing science, but that was the way things were done in the environment where they learned their trade. In many cases the rather severe exterior masks a kindly and generous nature, as it certainly does with Leonid.

I also remember a spell in the States as a visitor during which I heard two Russian cosmologists screaming at each other in the room next door. I really thought they were about to have a fist fight. A few minutes later, though, they both emerged, smiling as if nothing had happened…

Appropriately enough Leonid’s bash was held immediately after BritGrav 9, a meeting dedicated to bringing together the gravitational research community of the UK and beyond, and to provide a forum for the exchange of ideas. It aimed to cover all aspects of gravitational physics, both theoretical and experimental, including cosmology, mathematical general relativity, quantum gravity, gravitational astrophysics, gravitational wave data analysis, and instrumentation. I chaired a session during the meeting and found Leonid in characteristic form as a member of the audience, never shy with questions or comments, and quite difficult to keep under control.

I enjoyed the meeting because priority was given to students when allocating speaking slots. I think too many conferences have the same senior scientists giving the same talk over and over again. Relativists are also quite different to cosmologists in the level of mathematical rigour to which they aspire. You can bullshit at a cosmology conference, but wouldn’t get away with it in front of a GR audience.

On the evening of 16th April we had a public lecture in Cardiff by Kip Thorne on The Warped Side of the Universe: from the Big Bang to Black Holes and Gravitational Waves and Kip also gave a talk as part of the subsequent meeting on Friday in Leonid’s honour.

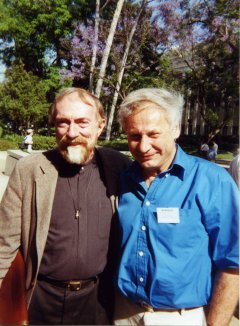

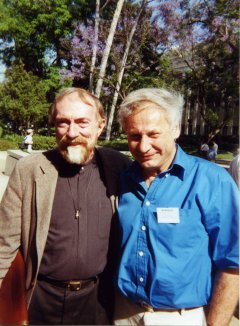

Kip and Leonid are shown together a few years ago in the photograph to the left here. The rest of the LPGFest meeting was interesting and eclectic, with talks from mathematical relativists as well as scientists in diverse fields who had come over from Russia specially to honour Leonid. We later adjourned to a “Welsh Banquet” at the 15th Century Undercroft of Cardiff Castle for dinner accompanied by something described as “entertainment” laid on by the hosts. That part was quite excruciating: like Butlins only not as classy. Heaven knows what our distinguished foreign visitors made of it, although Leonid seemed to think it was great fun, and that’s what matters.

Once the dinner was over it was time for Leonid to be showered with gifts from around the world and, by way of a finale, he was serenaded with a version of From Russian With Love, by Bernie and the Gravitones. Now at last I understand what the phrase “extraordinary rendition” means.

The idea is to use your skill, judgement and lugholes to detect the gravitational wave signal from the merger of two black holes in the noisy output of a gravitational wave detector. The image on the left shows the pattern of gravitational radiation as calculated numerically using Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Why not give it a try and see how you get on?

The idea is to use your skill, judgement and lugholes to detect the gravitational wave signal from the merger of two black holes in the noisy output of a gravitational wave detector. The image on the left shows the pattern of gravitational radiation as calculated numerically using Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Why not give it a try and see how you get on?