In my job here as Head of the School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences (MPS) at the University of Sussex, I’ve been been spending a lot of time recently on trying to understand the way the School’s budget works, sorting out what remains to be done for this financial year, and planning the budget for next year. In the course of doing all that it has become clear to me that the current funding arrangements from the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) are extremely worrying for Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) disciplines.

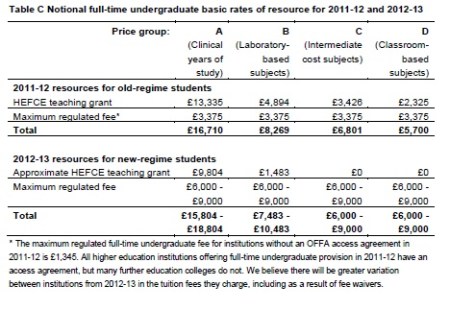

Before the introduction of the £9K tuition fees this academic year (i.e. in the `old regime’), a University would receive income from tuition fees of up to £3375 per student and from a `unit of resource’ or `teaching grant’ that depends on the subject. As shown in the upper part of Table C below which is taken from a HEFCE document:

In the old regime, the maximum income per student in Physics was thus £8,269 whereas for a typical Arts/Humanities student the maximum was £5,700. That means there was a 45% difference in funding between these two types of subject. The reason for this difference is that subjects such as physics are much more expensive to teach. Not only do disciplines like physics require expensive laboratory facilities (and associated support staff), they also involve many more contact hours between students and academic staff than in, e.g. an Arts subject. However, the differential is not as large as you might think: there’s only a factor two difference in teaching grant between the lowest band (D, including Sociology, Economics, Business Studies, Law and Education) and the STEM band B (including my own subject, Physics). The real difference in cost is much larger than that, and not just because science subjects need laboratories and the like.

To give an example, I was talking recently to a student from a Humanities department at a leading University (not my employer). Each week she gets 3 lectures and one two-hour seminar, the latter usually run by a research student. That’s it for her contact with the department. That meagre level of contact is by no means unusual, and some universities offer even less tuition than that.

In my School, MPS, a typical student can expect around 20 contact hours per week including lectures, exercise classes, laboratory sessions, and a tutorial (usually in a group of four). The vast majority of these sessions are done by full-time academic staff, not PDRAs or PhD students, although we do employ such folks in laboratory sessions and for a very small number of lectures. It doesn’t take Albert Einstein to work out that 20 hours of staff time costs a lot more than 3, and that’s even before you include the cost of the laboratories and equipment needed to teach physics.

Now look at what happens in the `new regime’, as displayed in the lower table in the figure. In the current system, students still pay the same fee for STEM and non-STEM subjects (£9K in most HEIs) but the teaching grant is now £1483 for Physics and nothing at all for Bands C and D. The difference in income is thus just £1,483 or in percentage terms, a difference of just 16.4. Worse than this, there’s no requirement that this extra resource be spent on the disciplines with which it is associated anyway. In most universities, all the tuition income goes into central coffers and is dispersed to Schools and Departments according to the whims of the University Management.

Of course the new fee levels have led to an increase in income to Universities across all disciplines, which is welcome because it should allow institutions to improve the quality of their teaching bu purchasing better equipment, etc. But the current arrangements as a powerful disincentive for a university to invest in expensive subjects, such as Physics, relative to Arts & Humanities subjects such as English or History. It also rips off staff and students in those disciplines, the students because they are given very little teaching in return for their fee, and the staff because we have to work far harder than our colleagues in other disciplines, who fob off most of what little teaching their supposed to do onto PhD students badged as Teaching Assistants. It is fortunate for this country that scientists working in its universities show such immense dedication to teaching as well as research that they’re prepared to carry on working in a University environment that is so clearly biased against STEM disciplines.

To get another angle on this argument, consider the comments made by senior members of the legal profession who are concerned about the drastic overproduction of law graduates. Only about half those doing the Bar Professional Training Course after a law degree stand any chance of getting a job as a lawyer in the UK. Contrast this with the situation in science subjects, where we don’t even produce enough graduates to ensure that schools have an adequate supply of science teachers. The system is completely out of balance. Here at Sussex, only about a quarter of students take courses in STEM subjects; nationally the figure is even lower, around 20%…

I don’t see anything on the horizon that will alter this ridiculous situation. STEM subjects will continue to be stifled as universities follow the incentive to invest in cheaper subjects and will continue to overproduce graduates in other areas. The present Chief Executive of HEFCE is stepping down. Will whoever takes over from him have the guts to do anything about this anti-STEM bias?

I doubt the free-market ideologues in Westminster would even think of intervening either, because the only two possible changes are: (i) to increase the fee for STEM subjects relative to others; and (ii) to increase the teaching grant. Option (i) would lead to a collapse in demand for the very subjects it was intended to save and option (ii) would involve increasing public expenditure, which is anathema to the government even if it is an investment in the UK’s future. Or maybe it’s making a complete botch of the situation deliberately, as part of a cunning plan to encourage universities to go private?