I got home from a busy day on campus to find the 21st February issue of the Times Literary Supplement had landed on my doormat having arrived today, 27th February. It used to take a couple of weeks for my subscription copy to reach Ireland but recently the service has improved. Intriguingly, the envelope it comes in is postmarked Bratislava…

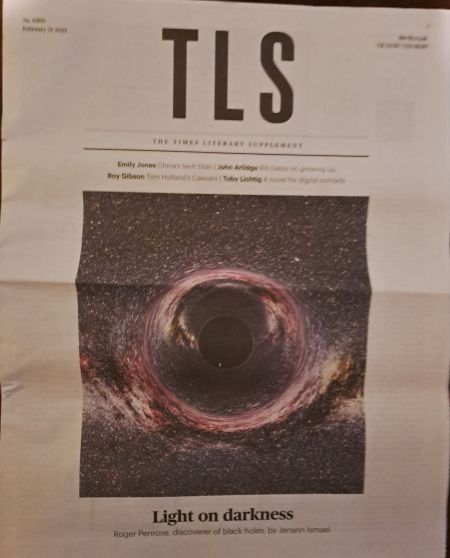

But I digress. This is the cover:

The text below the title “Light on darkness” under the graphic reads “Roger Penrose, discoverer of black holes, by Jennan Ismael”. Nice though it is to see science featured in the Times Literary Supplement for a change and much as I admire Roger Penrose, it is unreasonable to describe him as “the discoverer of black holes”.

A black hole represents a region of space-time where the action of gravity is sufficiently strong that light cannot escape. The idea that such a phenomenon might exist dates back to John Michell, an English clergyman, in 1783, and later by Pierre-Simon Laplace but black holes are most commonly associated with Einstein’s theory of general relativity. Indeed, one of the first exact solutions of Einstein’s equations to be found describes such an object. The famous Schwarzschild solution was obtained in 1915 by Karl Schwarzschild, who died soon after on the Eastern front in the First World War. The solution corresponds to a spherically-symmetric distribution of matter, and it was originally intended that it could form the basis of a mathematical model for a star. It was soon realised, however that for an object of any mass M there is a critical radius (Rs, the Schwarzschild radius) such that if all the mass is squashed inside Rs then no light can escape. In terms of the mass M, velocity of light c, and Newton’s constant G, the critical radius is given by Rs = 2GM/c2 . For the mass of the Earth, the critical radius is only 1cm, whereas for the Sun it is about 3km.

Since the pioneering work of Schwarzschild, research on black holes has been intense and other kinds of mathematical solutions have been obtained. For example, the Kerr solution describes a rotating black hole and the Reissner -Nordstrom solution corresponds to a black hole with an electric charge. Various theorems have also been demonstrated relating to the so-called `no-hair’ conjecture: that black holes give very little outward sign of what is inside.

Some people felt that the Schwarzschild solution was physically unrealistic as it required a completely spherical object, but Roger Penrose showed mathematically that the existence of a trapped surface was a generic consequence of gravitational collapse, the result that won him the Nobel Prize in 2020. His work did much to convince scientists of the physical reality of black holes, and he deserved his Nobel Prize, but I don’t think it is fair to say he “discovered” them.

I would say that, as is the case for discoveries in many branches of science, there isn’t just one “discoverer” of black holes: there were important contributions by many people along the way.

P.S. If you want to limit the application of the word “discovery” to observations then I think that the discovery of black holes is down to Paul Murdin and Louise Webster who identified the first really plausible candidate for a black hole in Cygnus X-1, way back in 1971…

P.P.S. The term “Black Hole” was, as far as I know, coined by John Wheeler in 1967.

Roger Penrose is 93.