The release of the latest batch of information relating to disgraced financier and sex offender Jeffrey Epstein got me thinking about the number of physicists on friendly terms with that individual and that in turn got me thinking about the Erdős Number, which I blogged about here, and about constructing some sort of metric relating to a person’s connecttion to Epstein.

The Erdős Number? It’s actually quite simple to define. First, Erdős himself is assigned an Erdős number of zero. Anyone who co-authored a paper with Erdős then has an Erdős number of 1. Then anyone who wrote a paper with someone who wrote a paper with Erdős has an Erdős number of 2, and so on. The Erdős number is thus a measure of “collaborative distance”, with lower numbers representing closer connections. A list of individuals with very low Erdős numbers (1, 2 or 3) can be found here. As it happens, mine is three.

The main difference between an Erdős Number and a putative Epstein Number is that most people think’s a nice thing to have a low Erdős Number whereas the opposite is probably the case for evidence of close collaboration with Jeffrey Epstein…

It is also difficult to define an equivalent to the Erdős Number for Epstein as the form of “colloboration” is less easily catergorised than publishing a paper. I think it is probably fairer to base a number simply on the number of people you know who met Epstein personally (assuming you didn’t know him yourself). Anyone who did know Epstein personally therefore gets an automatic red card. It would also be very difficult for a typical person to work out how many people they have met who have met someone who has met Epstein, etc.

I was intrigued by this because it is known that Epstein liked hanging out with scientists and, being a scientist myself, I wondered if anyone I knew had been drawn into the Epstein circle. It’s unreasonable to count anyone who appears in the Epstein files as having “known” Epstein because many of the names simply appear on emails sent by Epstein to which no reply was apparently ever received or which were not indicative of a working relationship or personal friendship, sometimes quite the opposite.

Anyway, based on a not very thorough bit of research I came across the following people who I have met in person who met and knew Jeffrey Epstein to a greater or lesser extent.

First, there’s Lawrence Krauss who left his position at Arizona State University as a consequence of a sexual misconduct case. He features prominently in the Epstein correspondence, including many messages about the disciplinary case brought against him at ASU. I met Lawrence Krauss in the 1990s at an Aspen Summer School for Physics, where I shared an office with him for about two weeks. I wouldn’t say that we got on well.

Second, there’s Harvard theoretical physicist Lisa Randall, whom I met at a meeting in South Africa about 25 years ago. The disturbing thing about her case is that she carried on interacting with Epstein even after his conviction for sex offences, visiting Epstein’s island home and travelling on his private jet.

Another name that comes up frequently in the Epstein files is John Brockman, a well-known literary agent. I met him at the Experiment Marathon in Reykjavik in 2008. In fact we were placed next to each other alphabetically speaking in the list of contributors:

Our conversations at that meeting were limited to small talk. As a matter of fact I didn’t really know who he was! He certainly didn’t offer me a lucrative book deal like he did with certain other physicists. The topic never arose.

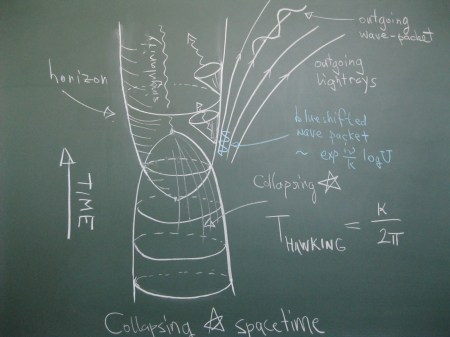

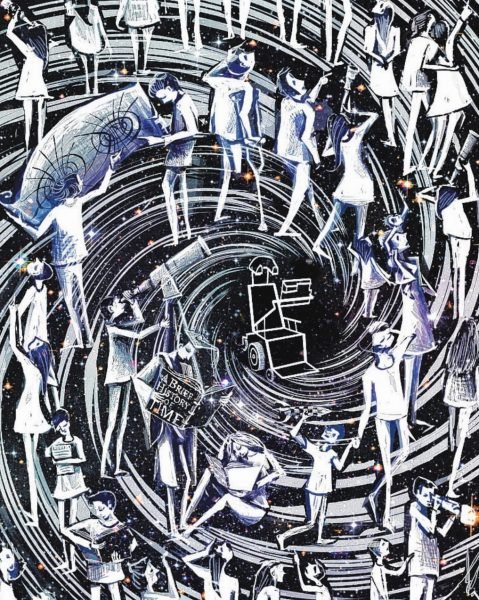

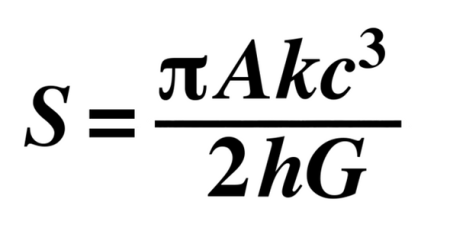

The files also contain references to Stephen Hawking (who died in 2018), including allegations about him made by Virginia Giuffre. Hawking was never charged with any crime but it is the case that he met Epstein at least once, at a meeting organized by Lawrence Krauss on St Thomas, close to Epstein Island. I met Stephen Hawking on a number of occasions.

Now you can add Lee Smolin, whom I met in Canada when I was on sabbatical in 2005. He has stepped back from his position at the Perimeter Institute after revelations that he maintained contact with Epstein after Epstein’s conviction for child sex offences.

So according to this my Epstein Number is four five. I have had no contact with any people who knew Epstein since 2008 and very little before that. Although it is perhaps indicative of a lack of eminence, I can’t say I’m sorry this number is low. I may have missed some, of course.

P.S. It is worth reading Peter Woit’s blog post on this topic and Scott Aaronson’s here.