Snowdrops by Lillias Mitchell (1929, watercolour on paper, 29 x 34 cm, National Gallery of Ireland); painted when the artist, who lived from 1915 to 2000, was 14 years old.

Archive for the Art Category

Snowdrops – Lillias Mitchell

Posted in Art with tags Lillias Mitchell, National Gallery of Ireland on February 11, 2026 by telescoperCosmic Spring I – František Kupka

Posted in Art with tags Art, Cosmic Spring I, František Kupka, National Gallery of Prague on February 3, 2026 by telescoperCosmis Spring I (Cosmic Spring I) by František Kupka (1913/4, oil on canvas, 115 x 125 cm, National Gallery of Prague).

Adapted from the Gallery catalogue:

František Kupka (1871-1957) wrote in his book Tvoření v umění výtvarném (Creation in Visual Art), that he did not seek to copy nature but sought inspiration in varied shapes of nature such as ice crystals, flower buds, freezing vapour, clouds, airflow, and falling stars. Kupka was fascinated by shape analogies which he found in various levels of microstructures and macrostructures – from microphotographs of cells to astronomical photographs of planets.

(Posted because, of course, 1st February was the first day of Spring…)

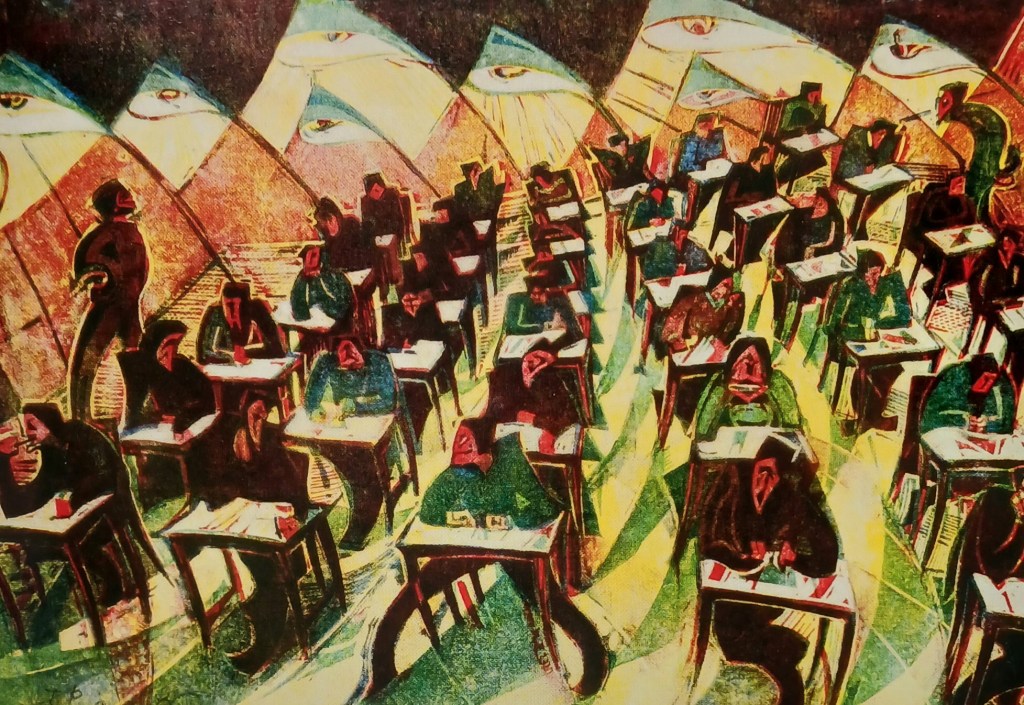

The Exam Room – Cyril E. Power

Posted in Art with tags Art, Cyril E. Power, Examinations, Linocut, The Met on January 15, 2026 by telescoperThe Exam Room by Cyril E. Power (c. 1934, linocut, 26.6 x 38.2 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; not on display)

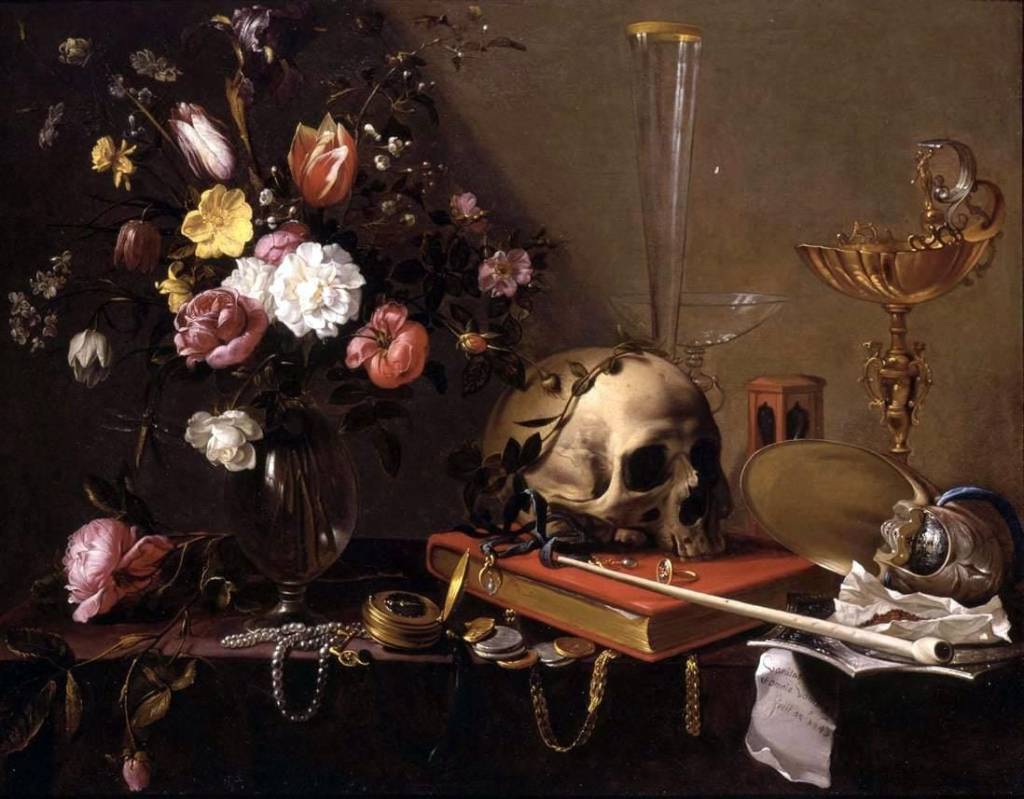

December 31st – Richard Hoffman

Posted in Art, Poetry with tags Art, December 31st, Memento Mori, Poem, Poetry, Richard Hoffman, Vanitas on December 31, 2025 by telescoperAll my undone actions wander

naked across the calendar,

a band of skinny hunter-gatherers,

blown snow scattered here and there,

stumbling toward a future

folded in the New Year I secure

with a pushpin: January’s picture

a painting from the 17th century,

a still life: Skull and mirror,

spilled coin purse and a flower.

by Richard Hofmann (b. 1949) from his collection Emblem.

I don’t know precisely which picture the poet is referring to for January in his calendar, nor which artist, but it it is undoubtedly an example of a Vanitas or Memento Mori, a genre symbolizing the transience of life, the futility of pleasure, and the certainty of death, and thus the vanity of ambition and all worldly desires. The paintings involved still life imagery of items suggessting the transitory nature of life.

A couple of examples are here:

Between them you find all the elements mentioned in the poem: the skull represents death, the flowers impermanence, the coins personal wealth and the other items worldly knowledge and pleasure. There’s an interesting WordPress blog about the symbolism this genre here:

P.S. My own calendar has pictures of tractors in it.

Alegoría del Invierno – Remedios Varo

Posted in Art with tags Alegoría del Invierno, Allegory of Winter, Art, painting, Remedios Varo, Remedios Varo Uranga on December 29, 2025 by telescoper

Alegoría del Invierno (Allegory of Winter) by Remedios Varo Uranga, 1948, gouache on paper, 44 ×44 cm, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain.

Art in Bruges

Posted in Art, Film with tags Art, Brendan Gleason, Colin Farrell, Hieronymous Bosch, In Bruges, The Last Judgment on December 19, 2025 by telescoperFor various reasons I find myself thinking about this little clip from the 2016 film In Bruges, starring Brendan Gleason and Colin Farrell. It’s set in the Groeningemuseum in the city of Bruges.

You can read an interesting post about the art in the film here.

You will see that the only painting that Ray (Colin Farrell) likes is a triptych called The Last Judgment, a version of which coincidentally featured in my post on Monday. The one I posted was by Hieronymous Bosch and is in Vienna; the one in Bruges is of doubtful attribution. It may be by Bosch, but experts think it is more likely to be by members of his workshop.

P.S. If you like black comedies then In Bruges is definitely for you! I wouldn’t say it was really a Christmas movie though…

The Last Judgment

Posted in Art, Maynooth with tags Das letzte Gericht, Hieronymous Bosch, Maynooth, Maynooth University, The Last Judgment on December 15, 2025 by telescoperWalking home through Maynooth this evening, the streets filled with partying students, I was reminded of this:

It’s the central part of the triptych Das letzte Gericht (The Last Judgment) by Hieronymus Bosch. The medium is oil on oak panel and it measures 164 x 127 cm. The original work is in the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna.

The figures at the top, looking down on the chaos, are clearly identifiable as members of academic staff, while those below are students. I’m sure that if Christmas jumpers had been invented in 1486, when the work is thought to have been completed, Bosch would have painted a few in…

Around the Circle – Wassily Kandinsky

Posted in Art with tags Around the Circle, Art, Wassily Kandinsky on December 10, 2025 by telescoperby Wassily Kandinsky (1940; oil and enamel on canvas. 96.8 x 146 cm Guggenheim, New York)

Euclid and the Dark Cloud

Posted in Art, Euclid, The Universe and Stuff with tags ESA, ESA Euclid, Euclid, European Space Agency, LDN 1641 on November 6, 2025 by telescoperI haven’t posted anything recently about the European Space Agency’s Euclid mission, but I can remedy that by passing on a new image with text from the accompanying press release. This is actually just one of a batch of new science results emerging from the first `Quick Release’ (Q1) data; I blogged about the first set of Q1 results here.

Incidentally, I find the picture is very reminiscent of a famous painting by James McNeill Whistler.

Image description: The focus of the image is a portion of LDN 1641, an interstellar nebula in the constellation of Orion. In this view, a deep-black background is sprinkled with a multitude of dots (stars) of different sizes and shades of bright white. Across the sea of stars, a web of fuzzy tendrils and ribbons in varying shades of orange and brown rises from the bottom of the image towards the top-right like thin coils of smoke.

Technical details: The colour image was created from NISP observations in the Y-, J- and H-bands, rendered blue, green and red, respectively. The size of the image is 11 232 x 12 576 pixels. The jagged boundary is due to the gaps in the array of NISP’s sixteen detectors, and the way the observations were taken with small spatial offsets and rotations to create the whole image. This is a common effect in astronomical wide-field images.

Accompanying Press Release

The above view of interstellar gas and dust was captured by the European Space Agency’s Euclid space telescope. The nebula is part of a so-called dark cloud, named LDN 1641. It sits at about 1300 light-years from Earth, within a sprawling complex of dusty gas clouds where stars are being formed, in the constellation of Orion.

This is because dust grains block visible light from stars behind them very efficiently but are much less effective at dimming near-infrared light.

The nebula is teeming with very young stars. Some of the objects embedded in the dusty surroundings spew out material – a sign of stars being formed. The outflows appear as magenta-coloured spots and coils when zooming into the image.

In the upper left, obstruction by dust diminishes and the view opens toward the more distant Universe with many galaxies lurking beyond the stars of our own galaxy.

Euclid observed this region of the sky in September 2023 to fine-tune its pointing ability. For the guiding tests, the operations team required a field of view where only a few stars would be detectable in visible light; this portion of LDN 1641 proved to be the most suitable area of the sky accessible to Euclid at the time.

The tests were successful and helped ensure that Euclid could point reliably and very precisely in the desired direction. This ability is key to delivering extremely sharp astronomical images of large patches of sky, at a fast pace. The data for this image, which is about 0.64 square degrees in size – or more than three times the area of the full Moon on the sky – were collected in just under five hours of observations.

Euclid is surveying the sky to create the most extensive 3D map of the extragalactic Universe ever made. Its main objective is to enable scientists to pin down the mysterious nature of dark matter and dark energy.

Yet the mission will also deliver a trove of observations of interesting regions in our galaxy, like this one, as well as countless detailed images of other galaxies, offering new avenues of investigation in many different fields of astronomy.

In visible light this region of the sky appears mostly dark, with few stars dotting what seems to be a primarily empty background. But, by imaging the cloud with the infrared eyes of its NISP instrument, Euclid reveals a multitude of stars shining through a tapestry of dust and gas.

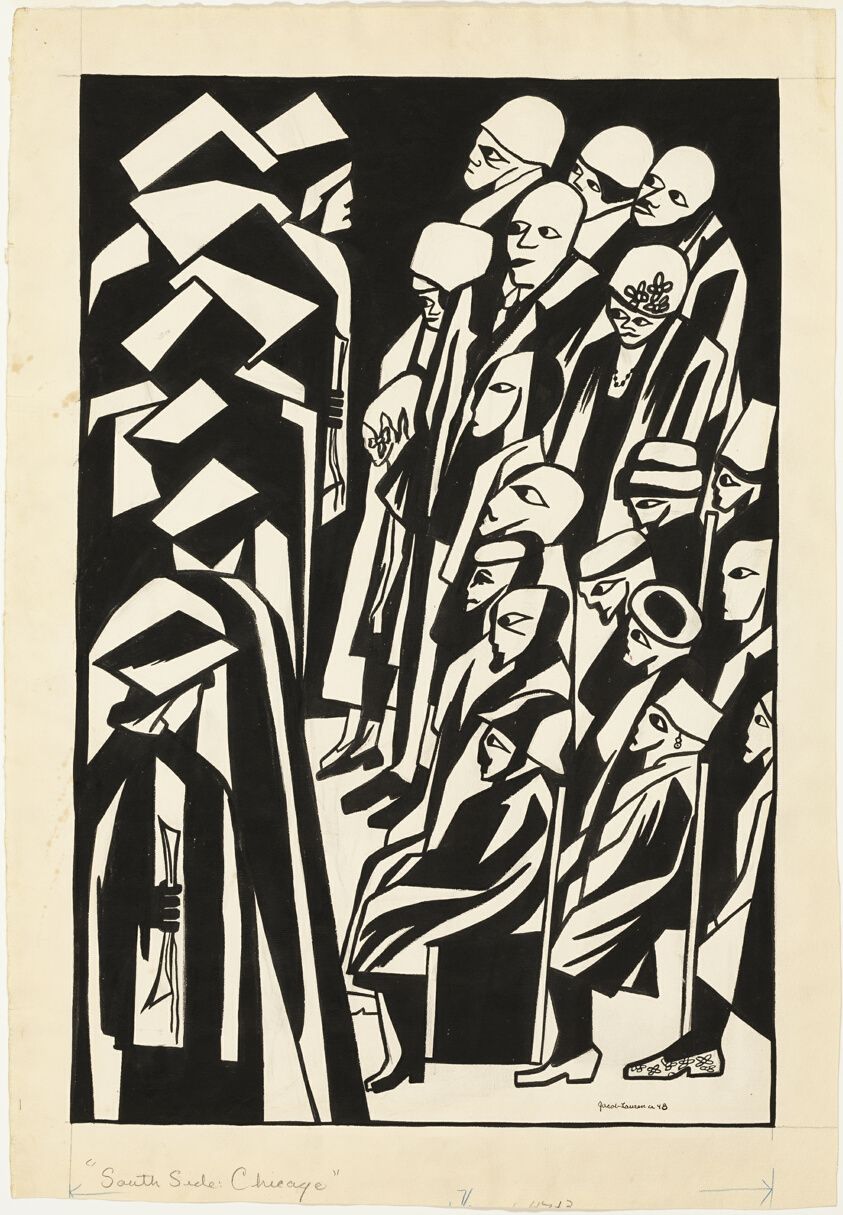

Graduation – Jacob Lawrence

Posted in Art, Poetry with tags Art, Graduation, Jacob Lawrence, Langston Hughes, Poetry on October 28, 2025 by telescoper

by Jacob Lawrence (1948, ink over graphite on paper, 72 × 49.8 cm, Art Institute of Chicago, USA)

This work, Graduation, is one of six drawings that Jacob Lawrence made as illustrations for Langston Hughes’s 1949 book of poetry, One-Way Ticket.