A few people at the STFC Summer School for new PhD students in Cardiff last week asked if I could share the slides. I’ve given the Powerpoint presentation to the organizers so presumably they will make the presentation available, but I thought I’d include it here too. I’ve corrected a couple of glitches I introduced trying to do some last-minute hacking just before my talk!

As you will inferfrom the slides, I decided not to compress an entire course on statistical methods into a one-hour talk. Instead I tried to focus on basic principles, primarily to get across the importance of Bayesian methods for tackling the usual tasks of hypothesis testing and parameter estimation. The Bayesian framework offers the only mathematically consistent way of tackling such problems and should therefore be the preferred method of using data to test theories. Of course if you have data but no theory or a theory but no data, any method is going to struggle. And if you have neither data nor theory you’d be better off getting one of the other before trying to do anything. Failing that, you could always go down the pub.

Rather than just leave it at that I thought I’d append some stuff I’ve written about previously on this blog, many years ago, about the interesting historical connections between Astronomy and Statistics.

Once the basics of mathematical probability had been worked out, it became possible to think about applying probabilistic notions to problems in natural philosophy. Not surprisingly, many of these problems were of astronomical origin but, on the way, the astronomers that tackled them also derived some of the basic concepts of statistical theory and practice. Statistics wasn’t just something that astronomers took off the shelf and used; they made fundamental contributions to the development of the subject itself.

The modern subject we now know as physics really began in the 16th and 17th century, although at that time it was usually called Natural Philosophy. The greatest early work in theoretical physics was undoubtedly Newton’s great Principia, published in 1687, which presented his idea of universal gravitation which, together with his famous three laws of motion, enabled him to account for the orbits of the planets around the Sun. But majestic though Newton’s achievements undoubtedly were, I think it is fair to say that the originator of modern physics was Galileo Galilei.

Galileo wasn’t as much of a mathematical genius as Newton, but he was highly imaginative, versatile and (very much unlike Newton) had an outgoing personality. He was also an able musician, fine artist and talented writer: in other words a true Renaissance man. His fame as a scientist largely depends on discoveries he made with the telescope. In particular, in 1610 he observed the four largest satellites of Jupiter, the phases of Venus and sunspots. He immediately leapt to the conclusion that not everything in the sky could be orbiting the Earth and openly promoted the Copernican view that the Sun was at the centre of the solar system with the planets orbiting around it. The Catholic Church was resistant to these ideas. He was hauled up in front of the Inquisition and placed under house arrest. He died in the year Newton was born (1642).

Galileo wasn’t as much of a mathematical genius as Newton, but he was highly imaginative, versatile and (very much unlike Newton) had an outgoing personality. He was also an able musician, fine artist and talented writer: in other words a true Renaissance man. His fame as a scientist largely depends on discoveries he made with the telescope. In particular, in 1610 he observed the four largest satellites of Jupiter, the phases of Venus and sunspots. He immediately leapt to the conclusion that not everything in the sky could be orbiting the Earth and openly promoted the Copernican view that the Sun was at the centre of the solar system with the planets orbiting around it. The Catholic Church was resistant to these ideas. He was hauled up in front of the Inquisition and placed under house arrest. He died in the year Newton was born (1642).

These aspects of Galileo’s life are probably familiar to most readers, but hidden away among scientific manuscripts and notebooks is an important first step towards a systematic method of statistical data analysis. Galileo performed numerous experiments, though he certainly didn’t carry out the one with which he is most commonly credited. He did establish that the speed at which bodies fall is independent of their weight, not by dropping things off the leaning tower of Pisa but by rolling balls down inclined slopes. In the course of his numerous forays into experimental physics Galileo realised that however careful he was taking measurements, the simplicity of the equipment available to him left him with quite large uncertainties in some of the results. He was able to estimate the accuracy of his measurements using repeated trials and sometimes ended up with a situation in which some measurements had larger estimated errors than others. This is a common occurrence in many kinds of experiment to this day.

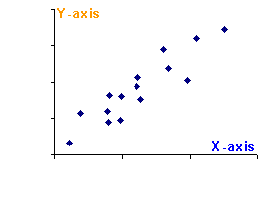

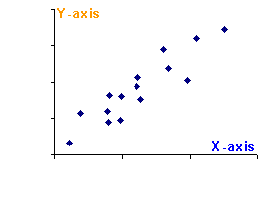

Very often the problem we have in front of us is to measure two variables in an experiment, say X and Y. It doesn’t really matter what these two things are, except that X is assumed to be something one can control or measure easily and Y is whatever it is the experiment is supposed to yield information about. In order to establish whether there is a relationship between X and Y one can imagine a series of experiments where X is systematically varied and the resulting Y measured. The pairs of (X,Y) values can then be plotted on a graph like the example shown in the Figure.

In this example on it certainly looks like there is a straight line linking Y and X, but with small deviations above and below the line caused by the errors in measurement of Y. This. You could quite easily take a ruler and draw a line of “best fit” by eye through these measurements. I spent many a tedious afternoon in the physics labs doing this sort of thing when I was at school. Ideally, though, what one wants is some procedure for fitting a mathematical function to a set of data automatically, without requiring any subjective intervention or artistic skill. Galileo found a way to do this. Imagine you have a set of pairs of measurements (xi,yi) to which you would like to fit a straight line of the form y=mx+c. One way to do it is to find the line that minimizes some measure of the spread of the measured values around the theoretical line. The way Galileo did this was to work out the sum of the differences between the measured yi and the predicted values mx+c at the measured values x=xi. He used the absolute difference |yi-(mxi+c)| so that the resulting optimal line would, roughly speaking, have as many of the measured points above it as below it. This general idea is now part of the standard practice of data analysis, and as far as I am aware, Galileo was the first scientist to grapple with the problem of dealing properly with experimental error.

The method used by Galileo was not quite the best way to crack the puzzle, but he had it almost right. It was again an astronomer who provided the missing piece and gave us essentially the same method used by statisticians (and astronomy) today.

Karl Friedrich Gauss (left) was undoubtedly one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, so it might be objected that he wasn’t really an astronomer. Nevertheless he was director of the Observatory at Göttingen for most of his working life and was a keen observer and experimentalist. In 1809, he developed Galileo’s ideas into the method of least-squares, which is still used today for curve fitting.

Karl Friedrich Gauss (left) was undoubtedly one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, so it might be objected that he wasn’t really an astronomer. Nevertheless he was director of the Observatory at Göttingen for most of his working life and was a keen observer and experimentalist. In 1809, he developed Galileo’s ideas into the method of least-squares, which is still used today for curve fitting.

This approach involves basically the same procedure but involves minimizing the sum of [yi-(mxi+c)]2 rather than |yi-(mxi+c)|. This leads to a much more elegant mathematical treatment of the resulting deviations – the “residuals”. Gauss also did fundamental work on the mathematical theory of errors in general. The normal distribution is often called the Gaussian curve in his honour.

After Galileo, the development of statistics as a means of data analysis in natural philosophy was dominated by astronomers. I can’t possibly go systematically through all the significant contributors, but I think it is worth devoting a paragraph or two to a few famous names.

I’ve already written on this blog about Jakob Bernoulli, whose famous book on probability was (probably) written during the 1690s. But Jakob was just one member of an extraordinary Swiss family that produced at least 11 important figures in the history of mathematics. Among them was Daniel Bernoulli who was born in 1700. Along with the other members of his famous family, he had interests that ranged from astronomy to zoology. He is perhaps most famous for his work on fluid flows which forms the basis of much of modern hydrodynamics, especially Bernouilli’s principle, which accounts for changes in pressure as a gas or liquid flows along a pipe of varying width.

But the elder Jakob’s work on gambling clearly also had some effect on Daniel, as in 1735 the younger Bernoulli published an exceptionally clever study involving the application of probability theory to astronomy. It had been known for centuries that the orbits of the planets are confined to the same part in the sky as seen from Earth, a narrow band called the Zodiac. This is because the Earth and the planets orbit in approximately the same plane around the Sun. The Sun’s path in the sky as the Earth revolves also follows the Zodiac. We now know that the flattened shape of the Solar System holds clues to the processes by which it formed from a rotating cloud of cosmic debris that formed a disk from which the planets eventually condensed, but this idea was not well established in the time of Daniel Bernouilli. He set himself the challenge of figuring out what the chance was that the planets were orbiting in the same plane simply by chance, rather than because some physical processes confined them to the plane of a protoplanetary disk. His conclusion? The odds against the inclinations of the planetary orbits being aligned by chance were, well, astronomical.

But the elder Jakob’s work on gambling clearly also had some effect on Daniel, as in 1735 the younger Bernoulli published an exceptionally clever study involving the application of probability theory to astronomy. It had been known for centuries that the orbits of the planets are confined to the same part in the sky as seen from Earth, a narrow band called the Zodiac. This is because the Earth and the planets orbit in approximately the same plane around the Sun. The Sun’s path in the sky as the Earth revolves also follows the Zodiac. We now know that the flattened shape of the Solar System holds clues to the processes by which it formed from a rotating cloud of cosmic debris that formed a disk from which the planets eventually condensed, but this idea was not well established in the time of Daniel Bernouilli. He set himself the challenge of figuring out what the chance was that the planets were orbiting in the same plane simply by chance, rather than because some physical processes confined them to the plane of a protoplanetary disk. His conclusion? The odds against the inclinations of the planetary orbits being aligned by chance were, well, astronomical.

The next “famous” figure I want to mention is not at all as famous as he should be. John Michell was a Cambridge graduate in divinity who became a village rector near Leeds. His most important idea was the suggestion he made in 1783 that sufficiently massive stars could generate such a strong gravitational pull that light would be unable to escape from them. These objects are now known as black holes (although the name was coined much later by John Archibald Wheeler). In the context of this story, however, he deserves recognition for his use of a statistical argument that the number of close pairs of stars seen in the sky could not arise by chance. He argued that they had to be physically associated, not fortuitous alignments. Michell is therefore credited with the discovery of double stars (or binaries), although compelling observational confirmation had to wait until William Herschel’s work of 1803.

It is impossible to overestimate the importance of the role played by Pierre Simon, Marquis de Laplace in the development of statistical theory. His book A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities, which began as an introduction to a much longer and more mathematical work, is probably the first time that a complete framework for the calculation and interpretation of probabilities ever appeared in print. First published in 1814, it is astonishingly modern in outlook.

It is impossible to overestimate the importance of the role played by Pierre Simon, Marquis de Laplace in the development of statistical theory. His book A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities, which began as an introduction to a much longer and more mathematical work, is probably the first time that a complete framework for the calculation and interpretation of probabilities ever appeared in print. First published in 1814, it is astonishingly modern in outlook.

Laplace began his scientific career as an assistant to Antoine Laurent Lavoiser, one of the founding fathers of chemistry. Laplace’s most important work was in astronomy, specifically in celestial mechanics, which involves explaining the motions of the heavenly bodies using the mathematical theory of dynamics. In 1796 he proposed the theory that the planets were formed from a rotating disk of gas and dust, which is in accord with the earlier assertion by Daniel Bernouilli that the planetary orbits could not be randomly oriented. In 1776 Laplace had also figured out a way of determining the average inclination of the planetary orbits.

A clutch of astronomers, including Laplace, also played important roles in the establishment of the Gaussian or normal distribution. I have also mentioned Gauss’s own part in this story, but other famous astronomers played their part. The importance of the Gaussian distribution owes a great deal to a mathematical property called the Central Limit Theorem: the distribution of the sum of a large number of independent variables tends to have the Gaussian form. Laplace in 1810 proved a special case of this theorem, and Gauss himself also discussed it at length.

A general proof of the Central Limit Theorem was finally furnished in 1838 by another astronomer, Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel– best known to physicists for the functions named after him – who in the same year was also the first man to measure a star’s distance using the method of parallax. Finally, the name “normal” distribution was coined in 1850 by another astronomer, John Herschel, son of William Herschel.

A general proof of the Central Limit Theorem was finally furnished in 1838 by another astronomer, Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel– best known to physicists for the functions named after him – who in the same year was also the first man to measure a star’s distance using the method of parallax. Finally, the name “normal” distribution was coined in 1850 by another astronomer, John Herschel, son of William Herschel.

I hope this gets the message across that the histories of statistics and astronomy are very much linked. Aspiring young astronomers are often dismayed when they enter research by the fact that they need to do a lot of statistical things. I’ve often complained that physics and astronomy education at universities usually includes almost nothing about statistics, because that is the one thing you can guarantee to use as a researcher in practically any branch of the subject.

Over the years, statistics has become regarded as slightly disreputable by many physicists, perhaps echoing Rutherford’s comment along the lines of “If your experiment needs statistics, you ought to have done a better experiment”. That’s a silly statement anyway because all experiments have some form of error that must be treated statistically, but it is particularly inapplicable to astronomy which is not experimental but observational. Astronomers need to do statistics, and we owe it to the memory of all the great scientists I mentioned above to do our statistics properly.

Galileo wasn’t as much of a mathematical genius as Newton, but he was highly imaginative, versatile and (very much unlike Newton) had an outgoing personality. He was also an able musician, fine artist and talented writer: in other words a true Renaissance man. His fame as a scientist largely depends on discoveries he made with the telescope. In particular, in 1610 he observed the four largest satellites of Jupiter, the phases of Venus and sunspots. He immediately leapt to the conclusion that not everything in the sky could be orbiting the Earth and openly promoted the Copernican view that the Sun was at the centre of the solar system with the planets orbiting around it. The Catholic Church was resistant to these ideas. He was hauled up in front of the Inquisition and placed under house arrest. He died in the year Newton was born (1642).

Galileo wasn’t as much of a mathematical genius as Newton, but he was highly imaginative, versatile and (very much unlike Newton) had an outgoing personality. He was also an able musician, fine artist and talented writer: in other words a true Renaissance man. His fame as a scientist largely depends on discoveries he made with the telescope. In particular, in 1610 he observed the four largest satellites of Jupiter, the phases of Venus and sunspots. He immediately leapt to the conclusion that not everything in the sky could be orbiting the Earth and openly promoted the Copernican view that the Sun was at the centre of the solar system with the planets orbiting around it. The Catholic Church was resistant to these ideas. He was hauled up in front of the Inquisition and placed under house arrest. He died in the year Newton was born (1642).

But the elder Jakob’s work on gambling clearly also had some effect on Daniel, as in 1735 the younger Bernoulli published an exceptionally clever study involving the application of probability theory to astronomy. It had been known for centuries that the orbits of the planets are confined to the same part in the sky as seen from Earth, a narrow band called the Zodiac. This is because the Earth and the planets orbit in approximately the same plane around the Sun. The Sun’s path in the sky as the Earth revolves also follows the Zodiac. We now know that the flattened shape of the Solar System holds clues to the processes by which it formed from a rotating cloud of cosmic debris that formed a disk from which the planets eventually condensed, but this idea was not well established in the time of Daniel Bernouilli. He set himself the challenge of figuring out what the chance was that the planets were orbiting in the same plane simply by chance, rather than because some physical processes confined them to the plane of a protoplanetary disk. His conclusion? The odds against the inclinations of the planetary orbits being aligned by chance were, well, astronomical.

But the elder Jakob’s work on gambling clearly also had some effect on Daniel, as in 1735 the younger Bernoulli published an exceptionally clever study involving the application of probability theory to astronomy. It had been known for centuries that the orbits of the planets are confined to the same part in the sky as seen from Earth, a narrow band called the Zodiac. This is because the Earth and the planets orbit in approximately the same plane around the Sun. The Sun’s path in the sky as the Earth revolves also follows the Zodiac. We now know that the flattened shape of the Solar System holds clues to the processes by which it formed from a rotating cloud of cosmic debris that formed a disk from which the planets eventually condensed, but this idea was not well established in the time of Daniel Bernouilli. He set himself the challenge of figuring out what the chance was that the planets were orbiting in the same plane simply by chance, rather than because some physical processes confined them to the plane of a protoplanetary disk. His conclusion? The odds against the inclinations of the planetary orbits being aligned by chance were, well, astronomical. It is impossible to overestimate the importance of the role played by

It is impossible to overestimate the importance of the role played by  A general proof of the Central Limit Theorem was finally furnished in 1838 by another astronomer,

A general proof of the Central Limit Theorem was finally furnished in 1838 by another astronomer,