For last year’s words belong to last year’s language

And next year’s words await another voice.

And to make an end is to make a beginning.

From Four Quartets, ‘Little Gidding’ by T. S. Eliot.

So it’s New Year’s Day. Athbhliain faoi mhaise dhaoibh!

For me this brings the festive season to an end. I’ve been eating and drinking too much for the last week as one is supposed to. Last night I brought in the new year with a dish of roast duck and the last of the Christmas vegetables. I think I’ll be buying any sprouts and parsnips for a while. When the iron tongue of midnight told twelve, I had a glass of excellent Irish Whiskey in the form of Clonakilty Single Pot Still (46%). It has been a most enjoyable week, but heightened level of self-indulgence has been rather exhausting, and I’ll be taking things a bit easier for a few days before I go back to work on Monday. It’s hard work being a glutton.

Anyway, I thought I’d mention a few things looking forward to the New Year.

January will, as usual, be dominated by examinations, and especially the marking thereof. The first examination for which I am responsible is on January 12th. The examination, incidentally, will be held in the Glenroyal Hotel in Maynooth as the Sports Hall on campus – usually a major exam venue – is out of commission due to building work.

I have a couple of writing deadlines, in addition to having to correct the examinations, so it will be a busy January.

Then February sees the start of a new semester. I’ll be teaching Particle Physics again. I was a bit surprised to be asked to teach this again, as I was filling last year in for our resident particle physicist who was on sabbatical. I’m glad to be able to continue with it given the work I put in to do it last time. My other module is Computational Physics which I have taught at Maynooth every year since 2018, apart from 2024 when I was on sabbatical. This time, however, I will have to think hard about how to deal with the use of generative AI in the coursework.

Will I get to teach any astrophysics or cosmology at Maynooth before I retire? That’s looking very unlikely. I think it’s probable that the new academic year, starting in September, will find me teaching the same modules as last year.

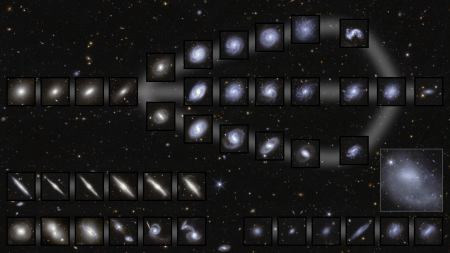

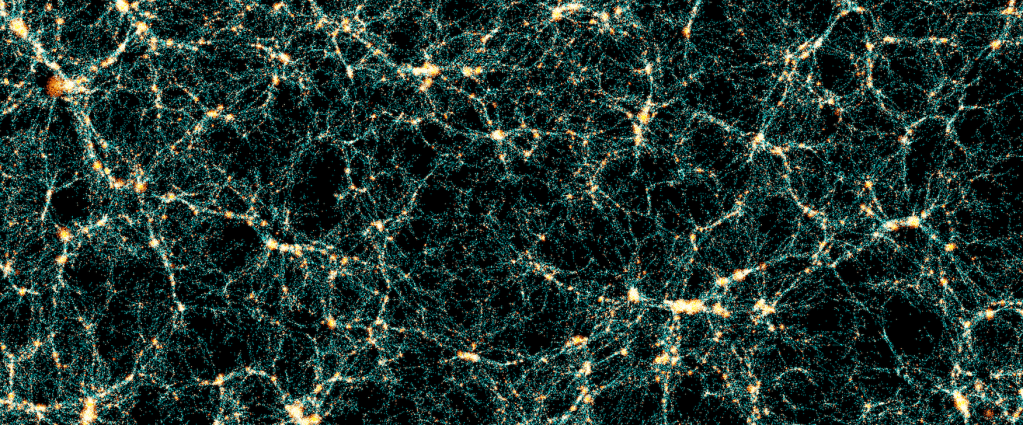

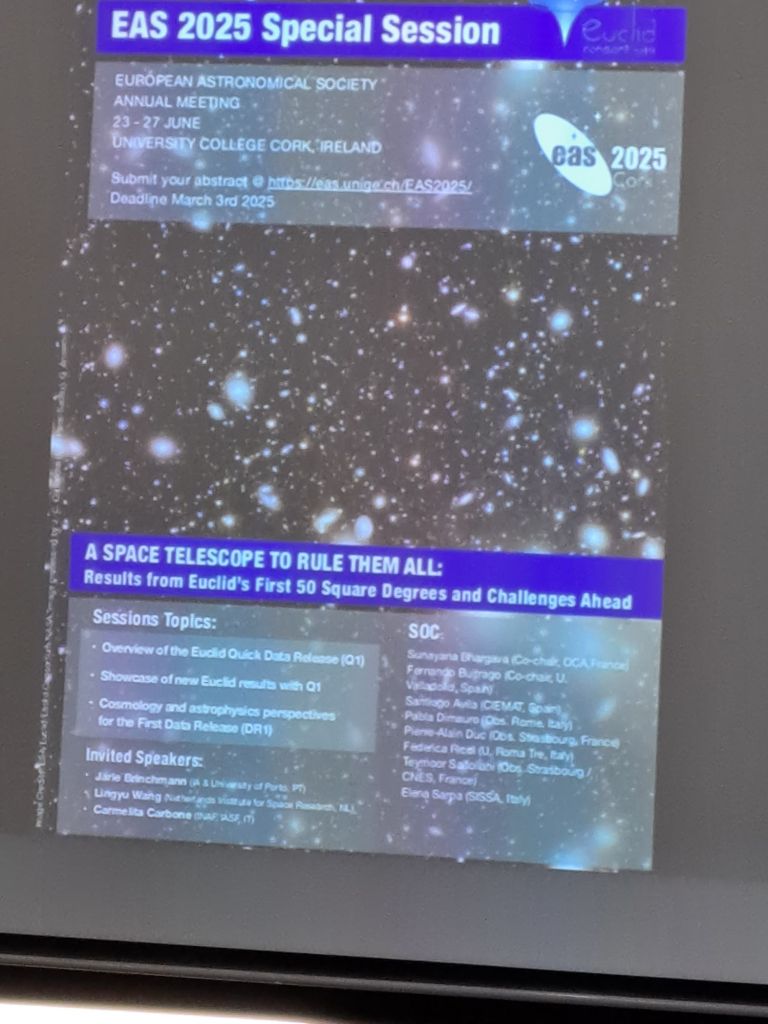

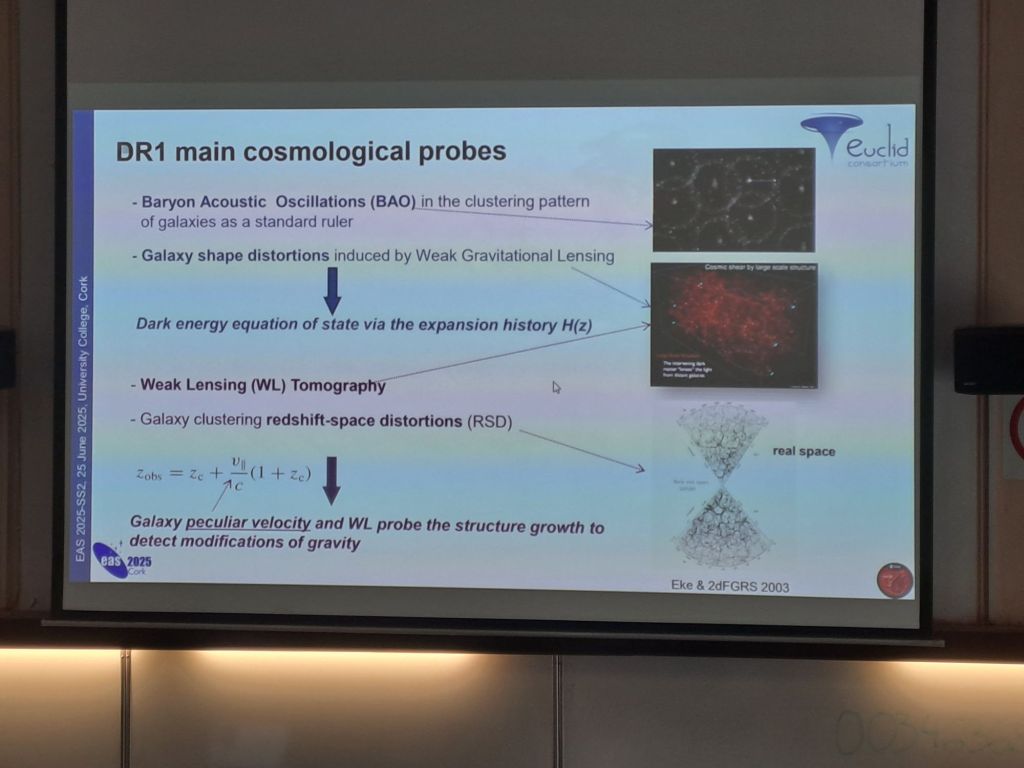

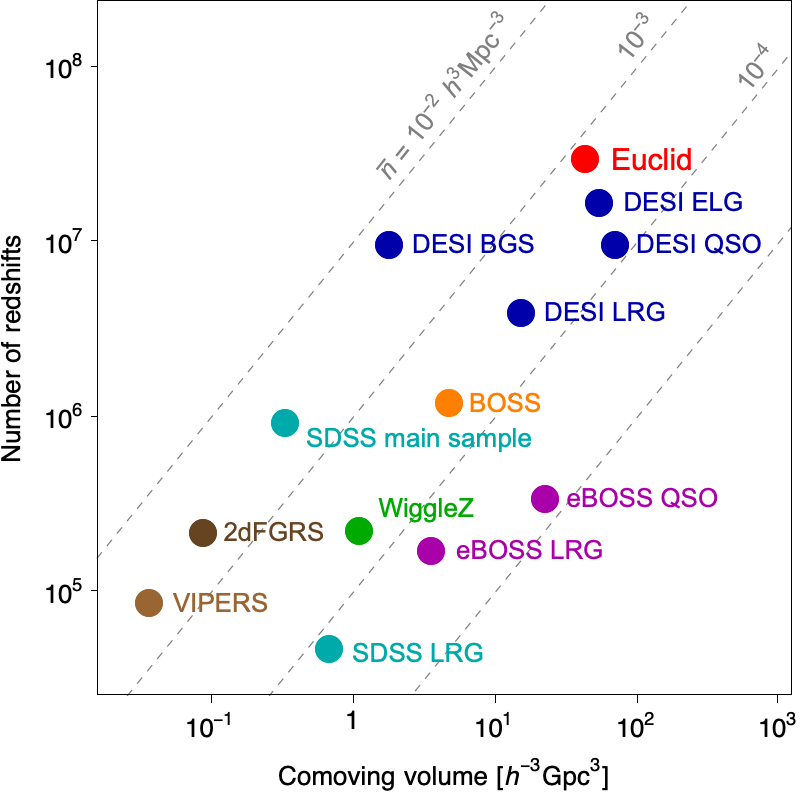

The year ahead will also see the first data release (DR1) from the European Space Agency’s Euclid Mission. The date for that will be October 21st 2026. This is a hard deadline. There’s a huge amount of work going on within the Euclid Consortium to extract as much science as possible from the observations so far before the data becomes public, but you’ll have to wait until October to find out more!

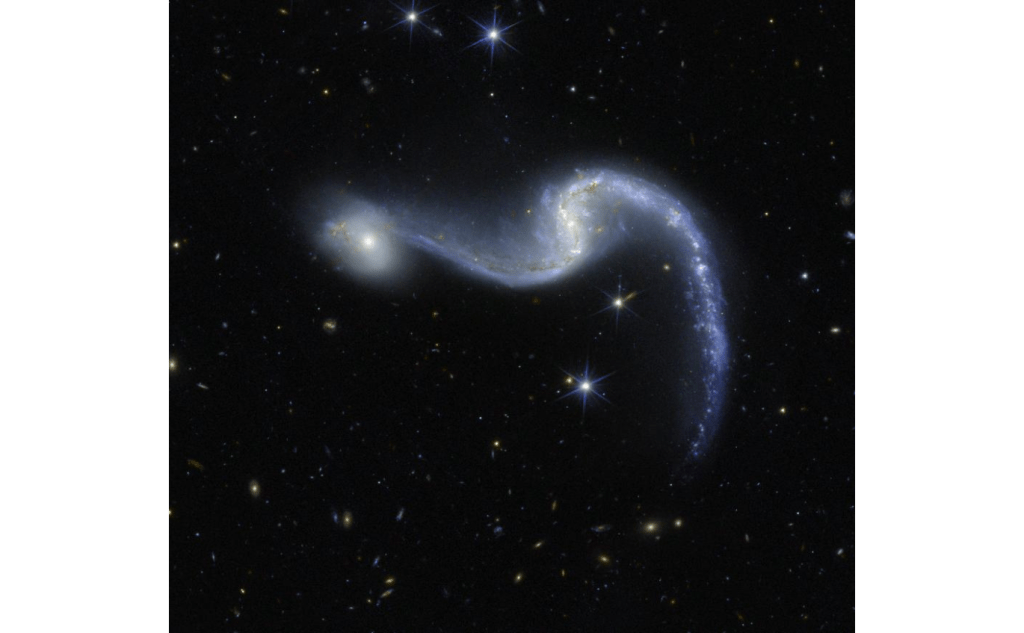

This reminds me that I forgot to share this nice image from Euclid that was released just before Christmas.

Once upon a time, WordPress used to send an email about the year’s blog statistics, etc, but it stopped doing that some time ago. I checked this morning, however, and learned that traffice on the blog in 2025 was up by 2.6% since 2024. I’m not sure how meaningful this is, because there is so much scraping going on these days. That figure doesn’t include the people who get posts via email or RSS or via other platforms such as the Fediverse.

While I’m on about social media I’ll mention a stat about my Bluesky account. I joined Bluesky in 2023 when I abandoned Xitter. As of today I have 8,078 BlueSky followers, which is more than I ever had on X, and with far higher levels of engagement and much friendlier interactions.

I’m also on Mastodon, although with a much smaller following (1.4k). This blog also has a separate existence on Mastodon here. I very much like the federated structure of Mastodon (which, incidentally, accords with my view of how academic publishing should be configured) and am a bit disappointed that it doesn’t seem to have caught on as much as it should.

That disappointment pales into insignificance, however, with the outrage I feel that my employer – along with most other universities – persists in using Xitter. Touting for trade in a far-right propaganda channel is no way for a institution of higher education to behave. You can read my views on this matter here.

And finally there’s the Open Journal of Astrophysics. The year ahead will see the 10th anniversary of our first ever publication – on an experimental prototype platform, long before we moved to Scholastica. It will be next Monday before we resume publishing, starting Volume 9. Which author(s) will be the first to get their final versions on arXiv in 2026? Stay tuned to find out!