My ongoing quest to keep up with the literature brings me to the winner of the 2023 Booker Prize, Prophet Song by Paul Lynch. Before writing a few comments on this extraordinary work I should mention the Maynooth connection: the book was written during the writer’s tenure as Writer-in-Residence at Maynooth University which involves teaching creativity and novel-writing, on the MA in Creative Writing, which is now in its second year.

So to the book, which is a grimly compelling novel set in an alternative Ireland after a far-right takeover revolving around Eilish Stack and her family. Her husband, Larry, a trade unionist, is detained by the state police and her efforts to find him get tangled up in the disintegration of society into civil war during which she tries desperately to keep herself and her family together as anarchy descends. We learn little of what goes on in the wider world, except what Eilish herself sees and rumours she picks up from others, but eventually, her home engulfed by the fighting, she is forced to attempt to flee with what remains of her family and cruelly exploited by human traffickers.

I won’t give away any details, but the story is bleak and at times is truly harrowing. I had to stop reading at one point – when Eilish visits a military hospital in the penultimate chapter, for those of you who have read it.

I have to admit that it took me a while to get the hang of Lynch’s writing style, with no conventional division into paragraphs and minimal punctuation. For example, speech is not included in quotation marks but embedded into the often very long sentences that blur the distinction between Eilish’s inner thoughts and the outer reality. Once I got used to it, however, I found it gripping despite the relentless horror of Eilish’s situation: Lynch conjures up an atmosphere of dread and hopelessness as effectively as George Orwell does in Nineteen Eighty-Four, with which this book has been rightly compared, but the prose also seems to me to be heavily influenced by James Joyce.

This is not an easy read, but is an important novel that should be read. I don’t think it will be long before it is on the syllabus for Leaving Certificate English.

I’ll just make further comment. Many of the reviews I have read of this book describe it as an “alternative future” and a warning about the rise of the fascism, but that’s only a part of the story. To me, it’s not really an alternative future, but an alternative present. The point is all the horrors described in this book – the murders, the abductions, the torture, the indiscriminate slaughter of innocent civilians, the people trafficking are actually happening right now elsewhere in the world, but those of us living in safer places can view them from a safe distance or, more likely, just ignore them. The novel’s power is that it makes such things happen on the familiar streets of Dublin, making the unthinkable an alternative reality.

You have to wait until near the very end of the book for Paul Lynch to explain the title, which he says far more eloquently, essentially what I said in the preceding paragraph.

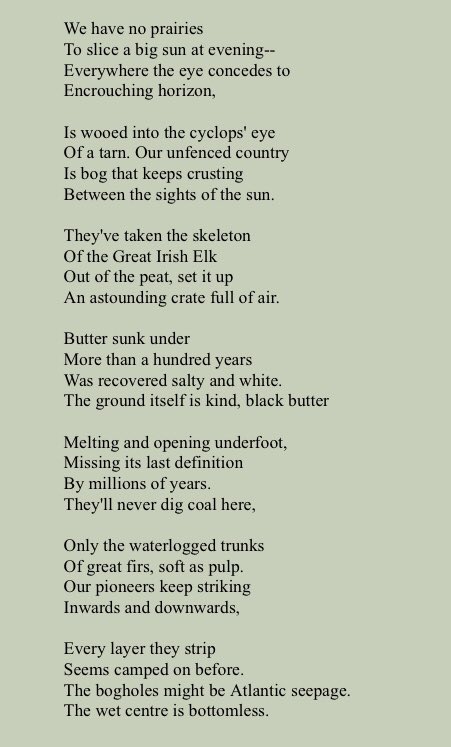

…and the prophet sings not of the end of the world but of what has been done and what will be done and what is being done to some but not others, that the world is always ending over and over again in one place but not another and that the end of the world is always a local event, it comes to your country and visits your town and knocks on the door of your house and becomes to others but some distant warning, a brief report on the news, an echo of events that has passed into folklore…

Paul Lynch, Prophet Song

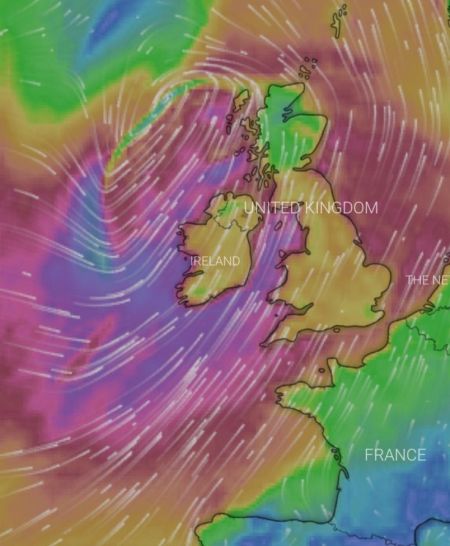

The tale ends with a crowd of refugees – Eilish and her young children among them – getting into small boats to attempt to reach safety across the sea. Frail as it is, that’s their only hope of survival and a better life…