I’ve been a bit busy today but I did notice at lunchtime that an old question has been going around on Twitter which gives me the excuse to post an old answer to it, what’s the difference between Astronomy and Astrophysics? This is something I’m asked quite often, and have blogged about before, but I thought I’d repeat it here for those who might stumble across it.

The Oxford English Dictionary gives the following primary definition for astronomy:

The science which treats of the constitution, relative positions, and motions of the heavenly bodies; that is, of all the bodies in the material universe outside of the earth, as well as of the earth itself in its relations to them.

Astrophysics, on the other hand, is described as

That branch of astronomy which treats of the physical or chemical properties of the celestial bodies.

So astrophysics is regarded as a subset of astronomy which is primarily concerned with understanding the properties of stars and galaxies, rather than just measuring their positions and motions.

It is possible to assign a fairly precise date when astrophysics first came into use in English because, at least in the early years of the subject, it was almost exclusively associated with astronomical spectroscopy. Indeed the OED gives the following text as the first occurrence of astrophysics, in 1869:

As a subject for the investigations of the astro-physicist, the examination of the luminous spectras of the heavenly bodies has proved a remarkably fruitful one

The scientific analysis of astronomical spectra began with a paper by William Hyde Wollaston in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society Vol. 102, p. 378, 1802. He was the first person to notice the presence of dark bands in the optical spectrum of the Sun. These bands were subsequently analysed in great detail by Joseph von Fraunhofer in a paper published in 1814 and are now usually known as Fraunhofer lines. Technical difficulties made it impossible to obtain spectra of stars other than the Sun for a considerable time, but William Huggins finally succeeded in 1864. A drawing of his pioneering spectroscope is shown below.

Meanwhile, fundamental work by Gustav Kirchoff and Robert Bunsen had been helping to establish an understanding of the spectra produced by hot gases. The identification of features in the Sun’s spectrum with similar lines produced in laboratory experiments led to a breakthrough in our understanding of the Universe whose importance shouldn’t be underestimated. The Sun and stars were inaccessible to direct experimental test during the 19th Century (as they are now). But spectroscopy now made it possible to gather evidence about their chemical composition as well as physical properties. Most importantly, spectroscopy provided definitive evidence that the Sun wasn’t made of some kind of exotic unknowable celestial material, but of the same kind of stuff (mainly Hydrogen) that could be studied on Earth. This realization opened the possibility of applying the physical understanding gained from small-scale experiments to the largest scale phenomena that could be seen. The science of astrophysics was born.

One of the leading journals in which professional astronomers and astrophysicists publish their research is called the Astrophysical Journal, which was founded in 1895 and is still going strong. The central importance of the (still) young field of spectroscopy can be appreciated from the subtitle given to the journal:

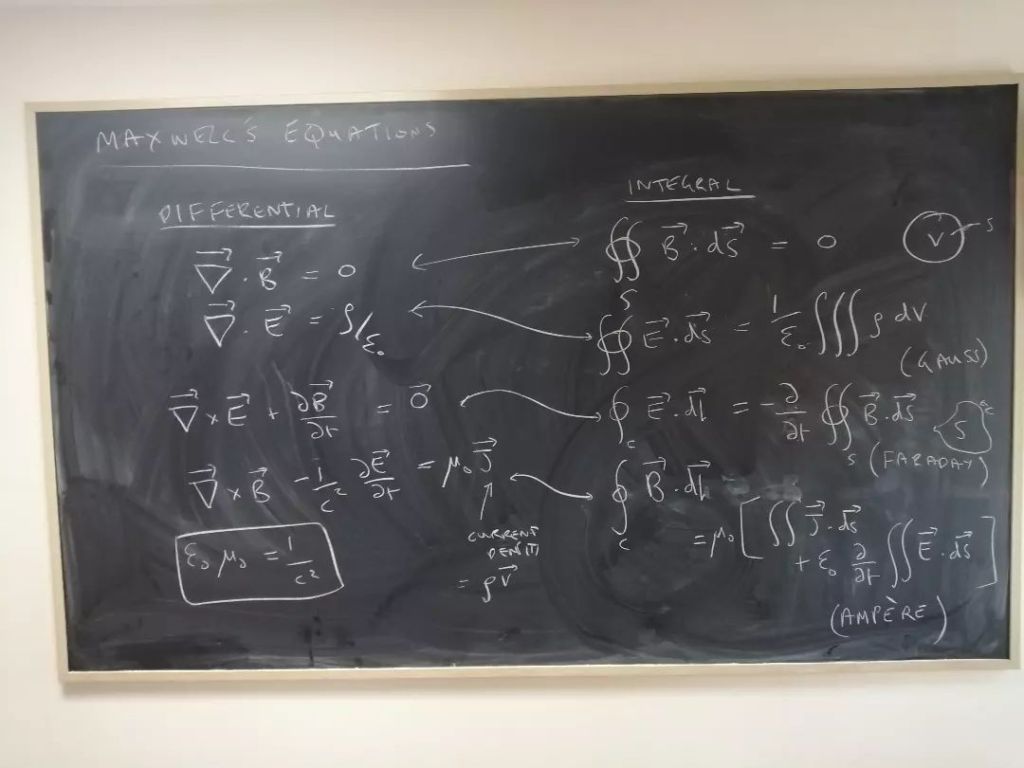

Initially the branch of physics most important to astrophysics was atomic physics since the lines in optical spectra are produced by electrons jumping between different atomic energy levels. Spectroscopy of course remains a key weapon in the astrophysicist’s arsenal but nowadays the term astrophysics is taken to mean any application of physical laws to astronomical objects. Over the years, astrophysics has therefore gradually incorporated nuclear and particle physics as well as thermodynamics, relativity and just about every other branch of physics you can think of.

I realize, however, that this isn’t really the answer to the question that potential students want to ask. What they (probably) want to know is what is the difference between undergraduate courses called Astronomy and those called Astrophysics? The answer to this one depends very much on where you want to study. Generally speaking the differences are in fact quite minimal. You probably do a bit more theory in an Astrophysics course than an Astronomy course, for example. Your final-year project might have to be observational or instrumental if you do Astronomy, but might be theoretical in Astrophysics. If you compare the complete list of modules to be taken, however, the difference will be very small.

Over the last twenty years or so, most Physics departments in the United Kingdom have acquired some form of research group in astronomy or astrophysics and have started to offer undergraduate degrees with some astronomical or astrophysical content. My only advice to prospective students wanting to find which course is for them is to look at the list of modules and projects likely to be offered. You’re unlikely to find the name of the course itself to be very helpful in making a choice.

To confuse things further, here in Maynooth there is a degree programme called Physics with Astrophysics which is taught primarily by the Department of Experimental Physics and has a heavy focus on observational techniques. If students want to do the interesting theoretical bits of Astrophysics, such as black holes and general relativity, they have to choose options with the Department of Theoretical Physics. As a theoretical astrophysicist I feel a bit frustrated by this.

One of the things that drew me into astrophysics as a discipline is that it involves such a wide range of techniques and applications, putting apparently esoteric things together in interesting ways to develop a theoretical understanding of a complicated phenomenon. I only had a very limited opportunity to study astrophysics during my first degree as I specialized in Theoretical Physics. This wasn’t just a feature of Cambridge. The attitude in most Universities in those days was that you had to learn all the physics before applying it to astronomy. Over the years this has changed, and most departments offer some astronomy right from Year 1.

I think this change has been for the better because I think the astronomical setting provides a very exciting context to learn physics. If you want to understand, say, the structure of the Sun you have to include atomic physics, nuclear physics, gravity, thermodynamics, radiative transfer and hydrostatics all at the same time. This sort of thing makes astrophysics a good subject for developing synthetic skills while more traditional physics teaching focusses almost exclusively on analytical skills.

I hope this clarifies the situation.