I thought I’d start a series of occasional posts about Bayesian probability. This is something I’ve touched on from time to time but its perhaps worth covering this relatively controversial topic in a slightly more systematic fashion especially with regard to how it works in cosmology.

I’ll start with Bayes’ theorem which for three logical propositions (such as statements about the values of parameters in theory) A, B and C can be written in the form

where

This is (or should be!) uncontroversial as it is simply a result of the sum and product rules for combining probabilities. Notice, however, that I’ve not restricted it to two propositions A and B as is often done, but carried throughout an extra one (C). This is to emphasize the fact that, to a Bayesian, all probabilities are conditional on something; usually, in the context of data analysis this is a background theory that furnishes the framework within which measurements are interpreted. If you say this makes everything model-dependent, then I’d agree. But every interpretation of data in terms of parameters of a model is dependent on the model. It has to be. If you think it can be otherwise then I think you’re misguided.

In the equation, P(B|C) is the probability of B being true, given that C is true . The information C need not be definitely known, but perhaps assumed for the sake of argument. The left-hand side of Bayes’ theorem denotes the probability of B given both A and C, and so on. The presence of C has not changed anything, but is just there as a reminder that it all depends on what is being assumed in the background. The equation states a theorem that can be proved to be mathematically correct so it is – or should be – uncontroversial.

Now comes the controversy. In the “frequentist” interpretation of probability, the entities A, B and C would be interpreted as “events” (e.g. the coin is heads) or “random variables” (e.g. the score on a dice, a number from 1 to 6) attached to which is their probability, indicating their propensity to occur in an imagined ensemble. These things are quite complicated mathematical objects: they don’t have specific numerical values, but are represented by a measure over the space of possibilities. They are sort of “blurred-out” in some way, the fuzziness representing the uncertainty in the precise value.

To a Bayesian, the entities A, B and C have a completely different character to what they represent for a frequentist. They are not “events” but logical propositions which can only be either true or false. The entities themselves are not blurred out, but we may have insufficient information to decide which of the two possibilities is correct. In this interpretation, P(A|C) represents the degree of belief that it is consistent to hold in the truth of A given the information C. Probability is therefore a generalization of the “normal” deductive logic expressed by Boolean algebra: the value “0” is associated with a proposition which is false and “1” denotes one that is true. Probability theory extends this logic to the intermediate case where there is insufficient information to be certain about the status of the proposition.

A common objection to Bayesian probability is that it is somehow arbitrary or ill-defined. “Subjective” is the word that is often bandied about. This is only fair to the extent that different individuals may have access to different information and therefore assign different probabilities. Given different information C and C′ the probabilities P(A|C) and P(A|C′) will be different. On the other hand, the same precise rules for assigning and manipulating probabilities apply as before. Identical results should therefore be obtained whether these are applied by any person, or even a robot, so that part isn’t subjective at all.

In fact I’d go further. I think one of the great strengths of the Bayesian interpretation is precisely that it does depend on what information is assumed. This means that such information has to be stated explicitly. The essential assumptions behind a result can be – and, regrettably, often are – hidden in frequentist analyses. Being a Bayesian forces you to put all your cards on the table.

To a Bayesian, probabilities are always conditional on other assumed truths. There is no such thing as an absolute probability, hence my alteration of the form of Bayes’s theorem to represent this. A probability such as P(A) has no meaning to a Bayesian: there is always conditioning information. For example, if I blithely assign a probability of 1/6 to each face of a dice, that assignment is actually conditional on me having no information to discriminate between the appearance of the faces, and no knowledge of the rolling trajectory that would allow me to make a prediction of its eventual resting position.

In tbe Bayesian framework, probability theory becomes not a branch of experimental science but a branch of logic. Like any branch of mathematics it cannot be tested by experiment but only by the requirement that it be internally self-consistent. This brings me to what I think is one of the most important results of twentieth century mathematics, but which is unfortunately almost unknown in the scientific community. In 1946, Richard Cox derived the unique generalization of Boolean algebra under the assumption that such a logic must involve associated a single number with any logical proposition. The result he got is beautiful and anyone with any interest in science should make a point of reading his elegant argument. It turns out that the only way to construct a consistent logic of uncertainty incorporating this principle is by using the standard laws of probability. There is no other way to reason consistently in the face of uncertainty than probability theory. Accordingly, probability theory always applies when there is insufficient knowledge for deductive certainty. Probability is inductive logic.

This is not just a nice mathematical property. This kind of probability lies at the foundations of a consistent methodological framework that not only encapsulates many common-sense notions about how science works, but also puts at least some aspects of scientific reasoning on a rigorous quantitative footing. This is an important weapon that should be used more often in the battle against the creeping irrationalism one finds in society at large.

I posted some time ago about an alternative way of deriving the laws of probability from consistency arguments.

To see how the Bayesian approach works, let us consider a simple example. Suppose we have a hypothesis H (some theoretical idea that we think might explain some experiment or observation). We also have access to some data D, and we also adopt some prior information I (which might be the results of other experiments or simply working assumptions). What we want to know is how strongly the data D supports the hypothesis H given my background assumptions I. To keep it easy, we assume that the choice is between whether H is true or H is false. In the latter case, “not-H” or H′ (for short) is true. If our experiment is at all useful we can construct P(D|HI), the probability that the experiment would produce the data set D if both our hypothesis and the conditional information are true.

The probability P(D|HI) is called the likelihood; to construct it we need to have some knowledge of the statistical errors produced by our measurement. Using Bayes’ theorem we can “invert” this likelihood to give P(H|DI), the probability that our hypothesis is true given the data and our assumptions. The result looks just like we had in the first two equations:

Now we can expand the “normalising constant” K because we know that either H or H′ must be true. Thus

The P(H|DI) on the left-hand side of the first expression is called the posterior probability; the right-hand side involves P(H|I), which is called the prior probability and the likelihood P(D|HI). The principal controversy surrounding Bayesian inductive reasoning involves the prior and how to define it, which is something I’ll comment on in a future post.

The Bayesian recipe for testing a hypothesis assigns a large posterior probability to a hypothesis for which the product of the prior probability and the likelihood is large. It can be generalized to the case where we want to pick the best of a set of competing hypothesis, say H1 …. Hn. Note that this need not be the set of all possible hypotheses, just those that we have thought about. We can only choose from what is available. The hypothesis may be relatively simple, such as that some particular parameter takes the value x, or they may be composite involving many parameters and/or assumptions. For instance, the Big Bang model of our universe is a very complicated hypothesis, or in fact a combination of hypotheses joined together, involving at least a dozen parameters which can’t be predicted a priori but which have to be estimated from observations.

The required result for multiple hypotheses is pretty straightforward: the sum of the two alternatives involved in K above simply becomes a sum over all possible hypotheses, so that

and

If the hypothesis concerns the value of a parameter – in cosmology this might be, e.g., the mean density of the Universe expressed by the density parameter Ω0 – then the allowed space of possibilities is continuous. The sum in the denominator should then be replaced by an integral, but conceptually nothing changes. Our “best” hypothesis is the one that has the greatest posterior probability.

From a frequentist stance the procedure is often instead to just maximize the likelihood. According to this approach the best theory is the one that makes the data most probable. This can be the same as the most probable theory, but only if the prior probability is constant, but the probability of a model given the data is generally not the same as the probability of the data given the model. I’m amazed how many practising scientists make this error on a regular basis.

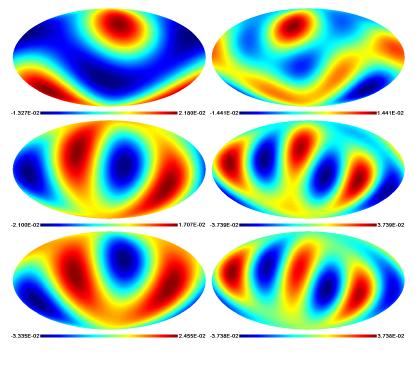

The following figure might serve to illustrate the difference between the frequentist and Bayesian approaches. In the former case, everything is done in “data space” using likelihoods, and in the other we work throughout with probabilities of hypotheses, i.e. we think in hypothesis space. I find it interesting to note that most theorists that I know who work in cosmology are Bayesians and most observers are frequentists!

As I mentioned above, it is the presence of the prior probability in the general formula that is the most controversial aspect of the Bayesian approach. The attitude of frequentists is often that this prior information is completely arbitrary or at least “model-dependent”. Being empirically-minded people, by and large, they prefer to think that measurements can be made and interpreted without reference to theory at all.

Assuming we can assign the prior probabilities in an appropriate way what emerges from the Bayesian framework is a consistent methodology for scientific progress. The scheme starts with the hardest part – theory creation. This requires human intervention, since we have no automatic procedure for dreaming up hypothesis from thin air. Once we have a set of hypotheses, we need data against which theories can be compared using their relative probabilities. The experimental testing of a theory can happen in many stages: the posterior probability obtained after one experiment can be fed in, as prior, into the next. The order of experiments does not matter. This all happens in an endless loop, as models are tested and refined by confrontation with experimental discoveries, and are forced to compete with new theoretical ideas. Often one particular theory emerges as most probable for a while, such as in particle physics where a “standard model” has been in existence for many years. But this does not make it absolutely right; it is just the best bet amongst the alternatives. Likewise, the Big Bang model does not represent the absolute truth, but is just the best available model in the face of the manifold relevant observations we now have concerning the Universe’s origin and evolution. The crucial point about this methodology is that it is inherently inductive: all the reasoning is carried out in “hypothesis space” rather than “observation space”. The primary form of logic involved is not deduction but induction. Science is all about inverse reasoning.

For comments on induction versus deduction in another context, see here.

So what are the main differences between the Bayesian and frequentist views?

First, I think it is fair to say that the Bayesian framework is enormously more general than is allowed by the frequentist notion that probabilities must be regarded as relative frequencies in some ensemble, whether that is real or imaginary. In the latter interpretation, a proposition is at once true in some elements of the ensemble and false in others. It seems to me to be a source of great confusion to substitute a logical AND for what is really a logical OR. The Bayesian stance is also free from problems associated with the failure to incorporate in the analysis any information that can’t be expressed as a frequency. Would you really trust a doctor who said that 75% of the people she saw with your symptoms required an operation, but who did not bother to look at your own medical files?

As I mentioned above, frequentists tend to talk about “random variables”. This takes us into another semantic minefield. What does “random” mean? To a Bayesian there are no random variables, only variables whose values we do not know. A random process is simply one about which we only have sufficient information to specify probability distributions rather than definite values.

More fundamentally, it is clear from the fact that the combination rules for probabilities were derived by Cox uniquely from the requirement of logical consistency, that any departure from these rules will generally speaking involve logical inconsistency. Many of the standard statistical data analysis techniques – including the simple “unbiased estimator” mentioned briefly above – used when the data consist of repeated samples of a variable having a definite but unknown value, are not equivalent to Bayesian reasoning. These methods can, of course, give good answers, but they can all be made to look completely silly by suitable choice of dataset.

By contrast, I am not aware of any example of a paradox or contradiction that has ever been found using the correct application of Bayesian methods, although method can be applied incorrectly. Furthermore, in order to deal with unique events like the weather, frequentists are forced to introduce the notion of an ensemble, a perhaps infinite collection of imaginary possibilities, to allow them to retain the notion that probability is a proportion. Provided the calculations are done correctly, the results of these calculations should agree with the Bayesian answers. On the other hand, frequentists often talk about the ensemble as if it were real, and I think that is very dangerous…

On the left you can see the breakdown of the various components involved in the standard model with the whole pie representing a flat Universe. You see there’s a vary strange mixture dominated by dark energy (which we don’t understand) and dark mattter (which we don’t understand). The bit we understand a little bit better (because we can sometimes see it directly) is only 4% of the whole thing. The proportions look very peculiar.

On the left you can see the breakdown of the various components involved in the standard model with the whole pie representing a flat Universe. You see there’s a vary strange mixture dominated by dark energy (which we don’t understand) and dark mattter (which we don’t understand). The bit we understand a little bit better (because we can sometimes see it directly) is only 4% of the whole thing. The proportions look very peculiar.