For those of you who are interested, here are the slides I used for the 1st Annual Robert Grosseteste Lecture on Astrophysics/Cosmology, given at the University of Lincoln on Thursday 23rd February 2017.

Follow @telescoperArchive for Cosmic Web.

The Cosmic Web – my Lincoln lecture slides…

Posted in Talks and Reviews, The Universe and Stuff with tags Cosmic Web., University of Lincoln on February 28, 2017 by telescoperThe Zel’dovich Lens

Posted in The Universe and Stuff with tags Cosmic Web., Johan Hidding, Large-scale Structure, Yakov Borisovich Zel'dovich, Zel'dovich Approximation on June 30, 2014 by telescoperBack to the grind after an enjoyable week in Estonia I find myself with little time to blog, so here’s a cute graphic by way of a postscript to the IAU Symposium on The Zel’dovich Universe. I’ve heard many times about this way of visualizing the Zel’dovich Approximation (published in Zeldovich, Ya.B. 1970, A&A, 5, 84) but this is by far the best graphical realization I have seen. Here’s the first page of the original paper:

In a nutshell, this daringly simple approximation considers the evolution of particles in an expanding Universe from an early near-uniform state into the non-linear regime as a sort of ballistic, or kinematic, process. Imagine the matter particles are initial placed on a uniform grid, where they are labelled by Lagrangian coordinates . Their (Eulerian) positions at some later time

are taken to be

Here the coordinates are comoving, i.e. scaled with the expansion of the Universe using the scale factor

. The displacement

between initial and final positions in comoving coordinates is taken to have the form

where is a kind of velocity potential (which is also in linear Newtonian theory proportional to the gravitational potential).If we’ve got the theory right then the gravitational potential field defined over the initial positions is a Gaussian random field. The function

is the growing mode of density perturbations in the linear theory of gravitational instability.

This all means that the particles just get a small initial kick from the uniform Lagrangian grid and their subsequent motion carries on in the same direction. The approximation predicts the formation of caustics in the final density field when particles from two or more different initial locations arrive at the same final location, a condition known as shell-crossing. The caustics are identified with the walls and filaments we find in large-scale structure.

Despite its simplicity this approximation is known to perform extremely well at reproducing the morphology of the cosmic web, although it breaks down after shell-crossing has occurred. In reality, bound structures are formed whereas the Zel’dovich approximation simply predicts that particles sail straight through the caustic which consequently evaporates.

Anyway the mapping described above can also be given an interpretation in terms of optics. Imagine a uniform illumination field (the initial particle distribution) incident upon a non-uniform surface (e.g. the surface of the water in a swimming pool). Time evolution is represented by greater depths within the pool. The light pattern observed on the bottom of the pool (the final distribution) displays caustics with a very similar morphology to the Cosmic Web, except in two dimensions, obviously.

Here is a very short but very nice video by Johan Hidding showing how this works:

In this context, the Zel’dovich approximation corresponds to the limit of geometrical optics. More accurate approximations can presumably be developed using analogies with physical optics, but this programme has only just begun.

The Power Spectrum and the Cosmic Web

Posted in Bad Statistics, The Universe and Stuff with tags autocorrelation function, Cosmic Web., Cosmology, Galaxy redshift surveys, IAU308, Large-scale Structure, Power spectrum on June 24, 2014 by telescoperOne of the things that makes this conference different from most cosmology meetings is that it is focussing on the large-scale structure of the Universe in itself as a topic rather a source of statistical information about, e.g. cosmological parameters. This means that we’ve been hearing about a set of statistical methods that is somewhat different from those usually used in the field (which are primarily based on second-order quantities).

One of the challenges cosmologists face is how to quantify the patterns we see in galaxy redshift surveys. In the relatively recent past the small size of the available data sets meant that only relatively crude descriptors could be used; anything sophisticated would be rendered useless by noise. For that reason, statistical analysis of galaxy clustering tended to be limited to the measurement of autocorrelation functions, usually constructed in Fourier space in the form of power spectra; you can find a nice review here.

Because it is so robust and contains a great deal of important information, the power spectrum has become ubiquitous in cosmology. But I think it’s important to realise its limitations.

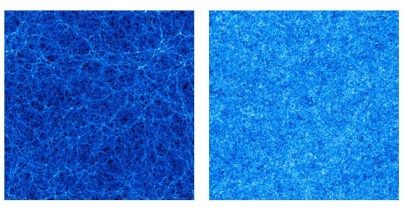

Take a look at these two N-body computer simulations of large-scale structure:

The one on the left is a proper simulation of the “cosmic web” which is at least qualitatively realistic, in that in contains filaments, clusters and voids pretty much like what is observed in galaxy surveys.

To make the picture on the right I first took the Fourier transform of the original simulation. This approach follows the best advice I ever got from my thesis supervisor: “if you can’t think of anything else to do, try Fourier-transforming everything.”

Anyway each Fourier mode is complex and can therefore be characterized by an amplitude and a phase (the modulus and argument of the complex quantity). What I did next was to randomly reshuffle all the phases while leaving the amplitudes alone. I then performed the inverse Fourier transform to construct the image shown on the right.

What this procedure does is to produce a new image which has exactly the same power spectrum as the first. You might be surprised by how little the pattern on the right resembles that on the left, given that they share this property; the distribution on the right is much fuzzier. In fact, the sharply delineated features are produced by mode-mode correlations and are therefore not well described by the power spectrum, which involves only the amplitude of each separate mode. In effect, the power spectrum is insensitive to the part of the Fourier description of the pattern that is responsible for delineating the cosmic web.

If you’re confused by this, consider the Fourier transforms of (a) white noise and (b) a Dirac delta-function. Both produce flat power-spectra, but they look very different in real space because in (b) all the Fourier modes are correlated in such away that they are in phase at the one location where the pattern is not zero; everywhere else they interfere destructively. In (a) the phases are distributed randomly.

The moral of this is that there is much more to the pattern of galaxy clustering than meets the power spectrum…

Follow @telescoperIllustris, Cosmology, and Simulation…

Posted in The Universe and Stuff with tags Cosmic Web., Cosmology, galaxy formation, Illustris, Large-scale Structure, Oxford English Dictionary, simulation on May 8, 2014 by telescoperThere’s been quite a lot of news coverage over the last day or two emanating from a paper just out in the journal Nature by Vogelsberger et al. which describes a set of cosmological simulations called Illustris; see for example here and here.

The excitement revolves around the fact that Illustris represents a bit of a landmark, in that it’s the first hydrodynamical simulation with sufficient dynamical range that it is able to fully resolve the formation and evolution of individual galaxies within the cosmic web of large-scale structure.

The simulations obviously represent a tremendous piece or work; they were run on supercomputers in France, Germany, and the USA; the largest of them was run on no less than 8,192 computer cores and took 19 million CPU hours. A single state-of-the-art desktop computer would require more than 2000 years to perform this calculation!

There’s even a video to accompany it (shame about the music):

The use of the word “simulation” always makes me smile. Being a crossword nut I spend far too much time looking in dictionaries but one often finds quite amusing things there. This is how the Oxford English Dictionary defines SIMULATION:

1.

a. The action or practice of simulating, with intent to deceive; false pretence, deceitful profession.

b. Tendency to assume a form resembling that of something else; unconscious imitation.

2. A false assumption or display, a surface resemblance or imitation, of something.

3. The technique of imitating the behaviour of some situation or process (whether economic, military, mechanical, etc.) by means of a suitably analogous situation or apparatus, esp. for the purpose of study or personnel training.

So it’s only the third entry that gives the meaning intended to be conveyed by the usage in the context of cosmological simulations. This is worth bearing in mind if you prefer old-fashioned analytical theory and want to wind up a simulationist! In football, of course, you can even get sent off for simulation…

Reproducing a reasonable likeness of something in a computer is not the same as understanding it, but that is not to say that these simulations aren’t incredibly useful and powerful, not just for making lovely pictures and videos but for helping to plan large scale survey programmes that can go and map cosmological structures on the same scale. Simulations of this scale are needed to help design observational and data analysis strategies for, e.g., the forthcoming Euclid mission.

Follow @telescoperOne Hundred Years of Zel’dovich

Posted in The Universe and Stuff with tags Cosmic Web., Large-scale Structure, Sergei Shandarin, Yakov Borisovich Zel'dovich, Zel'dovich Approximation on March 12, 2014 by telescoperLovely weather today, but it’s also been an extremely busy day with meetings and teachings. I did realize yesterday however that I had forgotten to mark a very important centenary at the weekend. If I hadn’t been such a slacker that I took last Saturday off work I would probably have been reminded…

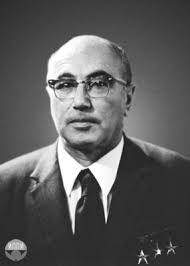

The great Russian physicist Yakov Borisovich Zel’dovich (left) was born on March 8th 1914, so had he lived he would have been 100 years old last Saturday. To us cosmologists Zel’dovich is best known for his work on the large-scale structure of the Universe, but he only started to work on that subject relatively late in his career during the 1960s. He in fact began his life in research as a physical chemist and arguably his greatest contribution to science was that he developed the first completely physically based theory of flame propagation (together with Frank-Kamenetskii). No doubt he also used insights gained from this work, together with his studies of detonation and shock waves, in the Soviet nuclear bomb programme in which he was a central figure, and which no doubt led to the chestful of medals he’s wearing in the photograph.

The great Russian physicist Yakov Borisovich Zel’dovich (left) was born on March 8th 1914, so had he lived he would have been 100 years old last Saturday. To us cosmologists Zel’dovich is best known for his work on the large-scale structure of the Universe, but he only started to work on that subject relatively late in his career during the 1960s. He in fact began his life in research as a physical chemist and arguably his greatest contribution to science was that he developed the first completely physically based theory of flame propagation (together with Frank-Kamenetskii). No doubt he also used insights gained from this work, together with his studies of detonation and shock waves, in the Soviet nuclear bomb programme in which he was a central figure, and which no doubt led to the chestful of medals he’s wearing in the photograph.

My own connection with Zel’dovich is primarily through his scientific descendants, principally his former student Sergei Shandarin, who has a faculty position at the University of Kansas. For example, I visited Kansas back in 1992 and worked on a project with Sergei and Adrian Melott which led to a paper published in 1993, the abstract of which makes it clear the debt it owed to the work of Ze’dovich.

The accuracy of various analytic approximations for following the evolution of cosmological density fluctuations into the nonlinear regime is investigated. The Zel’dovich approximation is found to be consistently the best approximation scheme. It is extremely accurate for power spectra characterized by n = -1 or less; when the approximation is ‘enhanced’ by truncating highly nonlinear Fourier modes the approximation is excellent even for n = +1. The performance of linear theory is less spectrum-dependent, but this approximation is less accurate than the Zel’dovich one for all cases because of the failure to treat dynamics. The lognormal approximation generally provides a very poor fit to the spatial pattern.

The Zel’dovich Approximation referred to in this abstract is based on an extremely simple idea but which, as we showed in the above paper, turns out to be extremely accurate at reproducing the morphology of the “cosmic web” of large-scale structure.

Zel’dovich passed away in 1987. I was a graduate student at that time and had never had the opportunity to meet him. If I had done so I’m sure I would have found him fascinating and intimidating in equal measure, as I admired his work enormously as did everyone I knew in the field of cosmology. Anyway, a couple of years after his death a review paper written by himself and Sergei Shandarin was published, along with the note:

The Russian version of this review was finished in the summer of 1987. By the tragic death of Ya. B.Zeldovich on December 2, 1987, about four-fifths of the paper had been translated into English. Professor Zeldovich would have been 75 years old on March 8, 1989 and was vivid and creative until his last day. The theory of the structure of the universe was one of his favorite subjects, to which he made many note-worthy contributions over the last 20 years.

As one does if one is vain I looked down the reference list to see if any of my papers were cited. I’d only published one paper before Zel’dovich died so my hopes weren’t high. As it happens, though, my very first paper (Coles 1986) was there in the list. That’s still the proudest moment of my life!

Anyway, this post gives me the opportunity to advertise that there is a special meeting called The Zel’dovich Universe coming up this summer in Tallinn, Estonia. It looks a really interesting conference and I really hope I can find the time to fit it into my schedule. I’ve never been to Estonia…

Follow @telescoperThe Cosmic Web at Sussex

Posted in Books, Talks and Reviews, The Universe and Stuff with tags Cosmic Web., Cosmology on December 10, 2013 by telescoperYesterday I had the honour of giving an evening lecture for staff and students at the School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences at the University of Sussex. The event was preceded by a bit of impromptu twilight stargazing with the new telescope our students have just purchased:

You can just about see Venus in the second picture, just to the left of the street light.

Anyway, after briefly pretending to be a proper astronomer it was down to my regular business as a cosmologist and my talk entitled The Cosmic Web. Here is the abstract:

The lecture will focus on the large-scale structure of the Universe and the ideas that physicists are weaving together to explain how it came to be the way it is. Over the last few decades, astronomers have revealed that our cosmos is not only vast in scale – at least 14 billion light years in radius – but also exceedingly complex, with galaxies and clusters of galaxies linked together in immense chains and sheets, surrounding giant voids of (apparently) empty space. Cosmologists have developed theoretical explanations for its origin that involve such exotic concepts as ‘dark matter’ and ‘cosmic inflation’, producing a cosmic web of ideas that is, in some ways, as rich and fascinating as the Universe itself.

And for those of you interested, here are the slides I used for your perusal:

It was quite a large (and very mixed) audience; it’s always difficult to pitch a talk at the right level in those circumstances so that it’s not too boring for the people who know something already but not too challenging for those who don’t know anything at all. A couple of people walked out about five minutes into the talk, which doesn’t exactly inspire a speaker with confidence, but overall it seemed to go down quite well.

Most of all, thank you to the organizers for the very nice reward of a bottle of wine!

Follow @telescoperPower versus Pattern

Posted in Bad Statistics, The Universe and Stuff with tags autocorrelation function, Cosmic Web., Cosmology, Galaxy redshift surveys, Large-scale Structure, Power spectrum on June 15, 2012 by telescoperOne of the challenges we cosmologists face is how to quantify the patterns we see in galaxy redshift surveys. In the relatively recent past the small size of the available data sets meant that only relatively crude descriptors could be used; anything sophisticated would be rendered useless by noise. For that reason, statistical analysis of galaxy clustering tended to be limited to the measurement of autocorrelation functions, usually constructed in Fourier space in the form of power spectra; you can find a nice review here.

Because it is so robust and contains a great deal of important information, the power spectrum has become ubiquitous in cosmology. But I think it’s important to realise its limitations.

Take a look at these two N-body computer simulations of large-scale structure:

The one on the left is a proper simulation of the “cosmic web” which is at least qualitatively realistic, in that in contains filaments, clusters and voids pretty much like what is observed in galaxy surveys.

To make the picture on the right I first took the Fourier transform of the original simulation. This approach follows the best advice I ever got from my thesis supervisor: “if you can’t think of anything else to do, try Fourier-transforming everything.”

Anyway each Fourier mode is complex and can therefore be characterized by an amplitude and a phase (the modulus and argument of the complex quantity). What I did next was to randomly reshuffle all the phases while leaving the amplitudes alone. I then performed the inverse Fourier transform to construct the image shown on the right.

What this procedure does is to produce a new image which has exactly the same power spectrum as the first. You might be surprised by how little the pattern on the right resembles that on the left, given that they share this property; the distribution on the right is much fuzzier. In fact, the sharply delineated features are produced by mode-mode correlations and are therefore not well described by the power spectrum, which involves only the amplitude of each separate mode.

If you’re confused by this, consider the Fourier transforms of (a) white noise and (b) a Dirac delta-function. Both produce flat power-spectra, but they look very different in real space because in (b) all the Fourier modes are correlated in such away that they are in phase at the one location where the pattern is not zero; everywhere else they interfere destructively. In (a) the phases are distributed randomly.

The moral of this is that there is much more to the pattern of galaxy clustering than meets the power spectrum…

Follow @telescoperMerseyside Astronomy Day

Posted in Books, Talks and Reviews, The Universe and Stuff with tags Cosmic Web., large-scale structure of the Universe, Merseyside, Merseyside Astronomy Day, The Midlands on May 11, 2012 by telescoperI’m just about to head by train off up to Merseyside (which, for those of you unfamiliar with the facts of British geography, is in the Midlands). The reason for this trip is that I’m due to give a talk tomorrow morning (Saturday 12th May) at Merseyside Astronomy Day, the 7th such event. It promises to be a MAD occasion.

My lecture, entitled The Cosmic Web, is an updated version of a talk I’ve given a number of times now; it will focus on the large scale structure of the Universe and the ideas that physicists are weaving together to explain how it came to be the way it is. Over the last few decades astronomers have revealed that our cosmos is not only vast in scale – at least 14 billion light years in radius – but also exceedingly complex, with galaxies and clusters of galaxies linked together in immense chains and sheets, surrounding giant voids of empty space. Cosmologists have developed theoretical explanations for its origin that involve such exotic concepts as ‘dark matter’ and ‘cosmic inflation’, producing a cosmic web of ideas that is in some ways as rich and fascinating as the Universe itself.

Anyway, I’m travelling to Liverpool this afternoon so I can meet the organizers for dinner this evening and stay overnight because there won’t be time to get there by train from Cardiff tomorrow morning. It’s not all that far from Cardiff to Liverpool as the crow flies, but unfortunately I’m not going by crow by train. I am nevertheless looking forward to seeing the venue, Spaceport, which I’ve never seen before.

If perchance any readers of this blog are planning to attend MAD VII please feel free to say hello. No doubt you will also tell me off for referring to Liverpool as the Midlands…

Follow @telescoperAstronomy in Darkness

Posted in The Universe and Stuff with tags astronomy, Cosmic Web., Cosmology, Dark Energy, dark matter, RAS Club, Royal Astronomical Society, Steve Rawlings, Tom Kitching on January 14, 2012 by telescoperYesterday, being the second Friday of the month, was the day for the Ordinary Meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society (followed by dinner at the Athenaeum for members of the RAS Club). Living and working in Cardiff it’s difficult for me to get the specialist RAS Meetings earlier in the day, but if I get myself sufficiently organized I can usually get to Burlington House in time for the 4pm start of the Ordinary Meeting, which is open to the public.

The distressing news we learnt on Thursday about the events of Wednesday night cast a shadow over the proceedings. Given that I was going to dinner afterwards, for which a jacket and tie are obligatory, I went through my collection of (rarely worn) ties, and decided that a black one would be appropriate. When I arrived at Burlington House I was just in time to hear a warm tribute paid by a clearly upset Professor Roger Davies, President of the RAS and Oxford colleague of the late Steve Rawlings. There then followed a minute’s silence in his memory.

The principal reaction to this news amongst the astronomers present was one of disbelief and/or incomprehension. Some friends and colleagues of Steve clearly knew much more about what had happened than has so far appeared in the press, but I don’t think it’s appropriate for me to make these public at this stage. We will know the facts soon enough. A colleague also pointed out to me that Steve had spent most of his recent working life as a central figure in the project to build the Square Kilometre Array, which will be the world’s largest radio telescope. He has died just a matter of days before the announcement will be made of where the SKA will actually be built. It’s sobering to think that one can spend so many years working on a project, only for something wholly unforeseen to prevent one seeing it through to completion.

Anyway, the meeting included an interesting talk by Tom Kitching of the University of Edinburgh who talked about recent results from the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope Lensing Survey (CHFTLenS). The same project was the subject of a press release because the results were presented earlier in the week at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Austin, Texas. I haven’t got time to go into the technicalities of this study – which exploits the phenomenon of weak gravitational lensing to reconstruct the distribution of unseen (dark) matter in the Universe through its gravitational effect on light from background sources – but Tom Kitching actually contributed a guest post to this blog some time ago which will give you some background.

In the talk he presented one of the first dark matter maps obtained from this survey, in which the bright colours represent regions of high dark matter density

Getting maps like this is no easy process, so this is mightily impressive work, but what struck me is that it doesn’t look very filamentary. In other words, the dark matter appears to reside predominantly in isolated blobs with not much hint of the complicated network of filaments we call the Cosmic Web. That’s a very subjective judgement, of course, and it will be necessary to study the properties of maps like this in considerable detail in order to see whether they really match the predictions of cosmological theory.

After the meeting, and a glass of wine in Burlington House, I toddled off to the Athenaeum for an extremely nice dinner. It being the Parish meeting of the RAS Club, afterwards we went through a number of items of Club business, including the election of four new members.

Life goes on, as does astronomy, even in darkness.

Follow @telescoperSDSS-III and the Cosmic Web

Posted in The Universe and Stuff with tags clusters of galaxies, Cosmic Web., Cosmology, galaxies, Sloan Digital Sky Survey SDSS, superclusters on January 12, 2011 by telescoperIt’s typical, isn’t it? You wait weeks for an interesting astronomical result to blog about and then two come along together…

Another international conference I’m not at is the 217th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society in the fine city of Seattle, which yesterday saw the release of some wonderful things produced by SDSS-III, the third incarnation of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. There’s a nice article about it in the Guardian, followed by the usual bizarre selection of comments from the public.

I particularly liked the following picture of the cosmic web of galaxies, clusters and filaments that pervades the Universe on scales of hundreds of millions of lightyears, although it looks to me like a poor quality imitation of a Jackson Pollock action painting:

The above image contains about 500 million galaxies, which represents an enormous advance in the quest to map the local structure of the Universe in as much detail as possible. It will also improve still further the precision with which cosmologists can analyse the statistical properties of the pattern of galaxy clustering.

The above represents only a part (about one third) of the overall survey; the following graphic shows how much of the sky has been mapped. It also represents only the imaging data, not the spectroscopic information and other information which is needed to analyse the galaxy distribution in full detail.

There’s also a short video zooming out from one galaxy to the whole Shebang.

The universe is a big place.