Just before the Christmas break I noticed a considerable amount of press coverage claiming that Dark Energy doesn’t exist. Much of the media discussion is closely based on a press release produced by the Royal Astronomical Society. Despite the excessive hype, and consequent initial scepticism, I think the paper has some merit and raises some interesting issues.

The main focus of the discussion is a paper (available on arXiv here) by Seifert et al. with the title Supernovae evidence for foundational change to cosmological models. This paper is accompanied by a longer article called Cosmological foundations revisited with Pantheon+ (also available on arXiv) by a permutation of the same authors, which goes into more detail about the analysis of supernova observations. If you want some background, the “standard” Pantheon+ supernova analysis is described in this paper. The reanalysis presented in the recent papers is motivated an idea called the Timescape model, which is not new. It was discussed by David Wiltshire (one of the authors of the recent papers) in 2007 here and in a number of subsequent papers; there’s also a long review article by Wiltshire here (dated 2013).

So what’s all the fuss about?

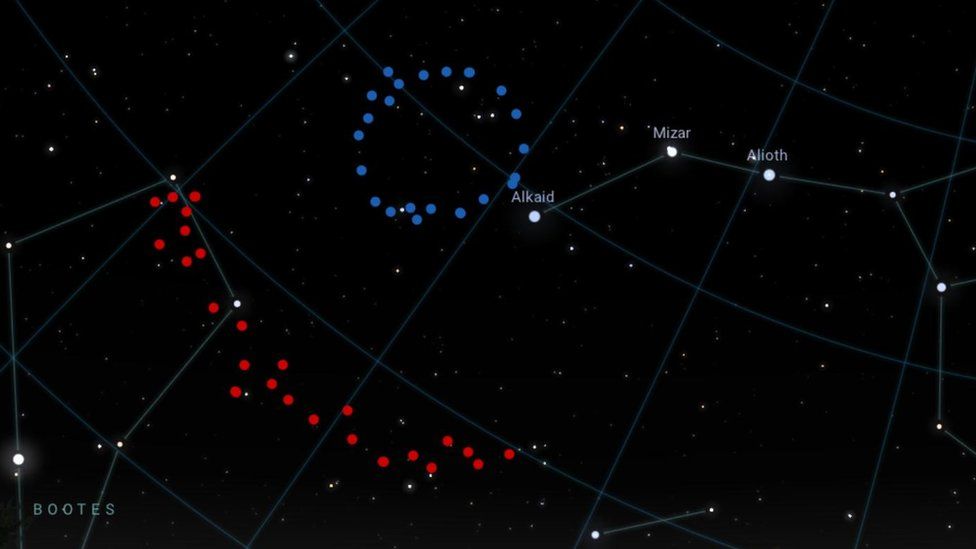

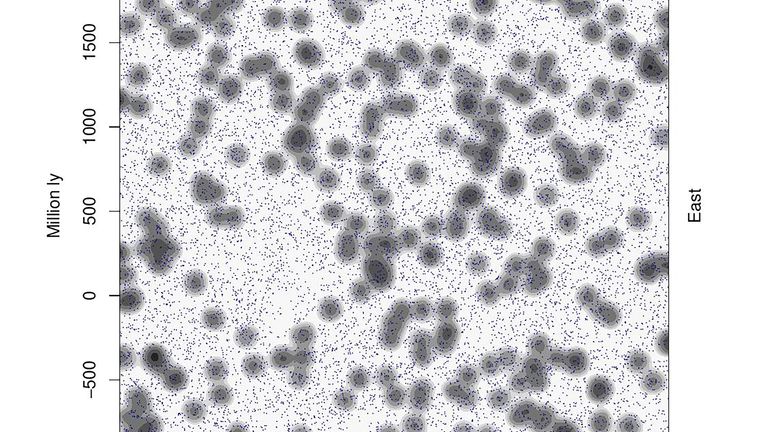

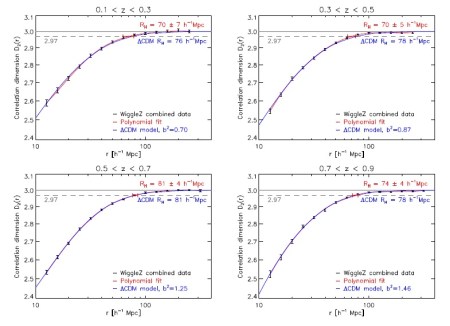

In the standard cosmological model we assume that, when sufficiently coarse-grained, the Universe obeys the Cosmological Principle, i.e. that it is homogeneous and isotropic. This implies that the space-time is described by a Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric (FLRW) metric. Of course we know that the Universe is not exactly smooth. There is a complex cosmic web of galaxies, filaments, clusters, and giant voids which comprise the large-scale structure of the Universe. In the standard cosmological model these fluctuations are treated as small perturbations on a smooth background which evolve linearly on large scales and don’t have a significant effect on the global evolution of the Universe.

This standard model is very successful in accounting for many things but only at the expense of introducing dark energy whose origin is uncertain but which accounts for about 70% of the energy density of the Universe. Among other things, this accounts for the apparent acceleration of the Universe inferred from supernovae measurements.

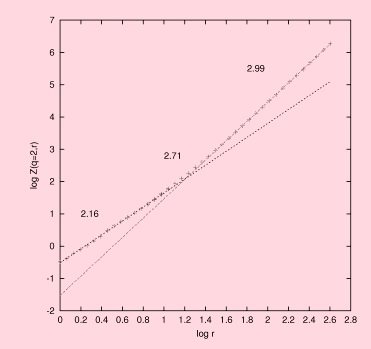

The approach taken in the Timescape model is to dispense with the FLRW metric, and the idea of separating the global evolution from the inhomogeneities. The idea instead is that the cosmic structure is essentially non-linear so there is no “background metric”. In this model, cosmological observations can not be analysed within the standard framework which relies on the FLRW assumption. Hence the need to reanalyse the supernova data. The name Timescape refers to the presence of significant gravitational time-dilation effects in this model as distinct from the standard model.

I wrote before in the context of a different paper:

….the supernovae measurements do not directly measure cosmic acceleration. If one tries to account for them with a model based on Einstein’s general relativity and the assumption that the Universe is on large-scales is homogeneous and isotropic and with certain kinds of matter and energy then the observations do imply a universe that accelerates. Any or all of those assumptions may be violated (though some possibilities are quite heavily constrained). In short we could, at least in principle, simply be interpreting these measurements within the wrong framework…

So what to make of the latest papers? I have to admit that I didn’t follow all the steps of the supernova reanalysis. I hope an expert can comment on this! I will therefore restrict myself to some general comments.

- My attitude to the standard cosmological model is that it is simply a working hypothesis and we should not elevate it to a status any higher than that. It is based not only on the Cosmological Principle (which could be false), but on the universal applicability of general relativity (which might not be true), and on a number of other assumptions that might not be true either.

- It is important to recognize that one of the reasons that the standard cosmology is the front-runner is that it provides a framework that enables relatively straightforward prediction and interpretation of cosmological measurements. That goes not only for supernova measurements but also for the cosmic microwave background, galaxy clustering, gravitational lensing, and so on. This is much harder to do accurately in the Timescape model simply because the equations involved are much more complex; there are few exact solutions of Einstein’s equations that can help. It is important that people work on alternatives such as this.

- Second, the idea that inhomogeneities might be much more important than assumed in the standard model has been discussed extensively in the literature over the last twenty years or so under the heading “backreaction”. My interpretation of the current state of play is that there are many unresolved questions, largely because of technical difficulties. See, for example, work by Thomas Buchert (here and, with many other collaborators here) and papers by Green & Wald (here and here). Nick Kasiser also wrote about it here.

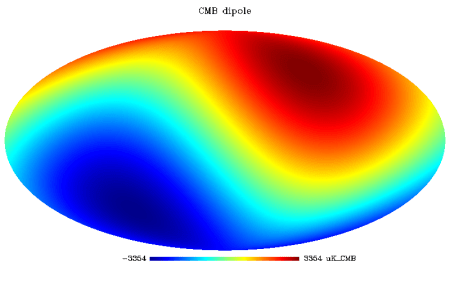

- The new papers under discussion focus entirely on supernovae measurements. It must be recognized that these provide just one of the pillars supporting the standard cosmology. Over the years, many alternative models have been suggested that claim to “fix” some alleged problem with cosmology only to find that it makes other issues worse. That’s not a reason to ignore departures from the standard framework, but it is an indication that we have a huge amount of data and we’re not allowed to cherry-pick what we want. We have to fit it all. The strongest evidence in favour of the FLRW framework actually comes from the cosmic microwave background (CMB) with the supernovae provide corroboration. I would need to see a detailed prediction of the anisotropy of the CMB before being convinced.

- The Timescape model is largely based on the non-linear expansion of cosmic voids. These are undoubtedly important, and there has been considerable observational and theoretical activity in understanding them and their evolution in the standard model. It is not at all obvious to me that the voids invoked to explain the apparent acceleration of the Universe are consistent with what we actually see in our surveys. That is something else to test.

- Finally, the standard cosmology includes a prescription for the initial conditions from which the present inhomogeneities grew. Where does the cosmic web come from in the Timescape model?

Anyway, I’m sure there’ll be a lot of discussion of this in the next few weeks as cosmologists return to the Universe from their Christmas holidays!

Comments are welcome through the box below, especially from people who have managed to understand the cos.