I’m a bit late getting onto the topic of dark matter in the Solar Neighbourhood, but it has been generating quite a lot of news, blogposts and other discussion recently so I thought I’d have a bash this morning. The result in question is a paper on the arXiv by Moni Bidin et al. which has the following abstract:

We measured the surface mass density of the Galactic disk at the solar position, up to 4 kpc from the plane, by means of the kinematics of ~400 thick disk stars. The results match the expectations for the visible mass only, and no dark matter is detected in the volume under analysis. The current models of dark matter halo are excluded with a significance higher than 5sigma, unless a highly prolate halo is assumed, very atypical in cold dark matter simulations. The resulting lack of dark matter at the solar position challenges the current models.

As far as I’m aware, Oort (1932, 1960) was the first to perform an analysis of the vertical equilibrium of the stellar distribution in the solar neighbourhood. He argued that there is more mass in the galactic disk than can be accounted for by star counts. A reanalysis of this problem by Bahcall (1984) argued for the presence of a dark “disk” of a scale height of about 700 pc. This was called into question by Bienaymé et al. (1987), and by Kuijken & Gilmore in 1989. In a later analysis based on a sample of stars with HIPPARCOS distances and Coravel radial velocities, within 125 pc of the Sun. Crézé et al. (1998) found that there is no evidence for dark matter in the disk of the Milky Way, claiming that all the matter is accounted for by adding up the contributions of gas, young stars and old stars.

The lack of evidence for dark matter in the Solar Neighbourhood is not therefore a particularly new finding; there’s never been any strong evidence that it is present in significant quantities out in the suburbs of the Milky Way where we reside. Indeed, I remember a big bust-up about this at a Royal Society meeting I attended in 1985 as a fledgling graduate student. Interesting that it’s still so controversial 27 years later.

Of course the result doesn’t mean that the dark matter isn’t there. It just means that its effect is too small compared to that of the luminous matter, i.e. stars, for it to be detected. We know that the luminous matter has to be concentrated more centrally than the dark matter, so it’s possible that the dark component is there, but does not have a significant effect on stellar motions near the Sun.

The latest, and probably most accurate, study has again found no evidence for dark matter in the vicinity of the Sun. If true, this may mean that attempts to detect dark matter particles using experiments on Earth are unlikely to be successful.

The team in question used the MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope at ESO’s La Silla Observatory, along with other telescopes, to map the positions and motions of more than 400 stars with distances up to 13000 light-years from the Sun. From these new data they have estimated the mass of material in a volume four times larger than ever considered before but found that everything is well explained by the gravitational effects of stars, dust and gas with no need for a dark matter component.

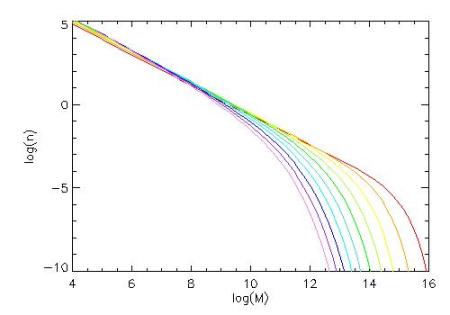

The reason for postulating the existence of large quantities of dark matter in spiral galaxies like the Milky Way is the motion of material in the outer parts, far from the Solar Neighbourhood (which is a mere 30,000 light years from Galactic Centre). These measurements are clearly inconsistent with the distribution of visible matter if our understanding of gravity is correct. So either there’s some invisible matter that gravitates or we need to reconsider our theories of gravitation. The dark matter explanation also fits with circumstantial evidence from other contexts (e.g. galaxy clusters), so is favoured by most astronomers. In the standard theory the Milky Way is surrounded by am extended halo of dark matter which is much less concentrated than the luminous material by virtue of it not being able to dissipate energy because it consists of particles that only interact weakly and can’t radiate. Luminous matter therefore outweighs dark matter in the cores of galaxies, but the situation is reversed in the outskirts. In between there should be some contribution from dark matter, but since it could be relatively modest it is difficult to estimate.

The study by Moni Bidin et al. makes a number of questionable assumptions about the shape of the Milky Way halo – they take it to be smooth and spherical – and the distribution of velocities within it is taken to have a very simple form. These may well turn out to be untrue. In any case the measurements they needed are extremely difficult to make, so they’ll need to be checked by other teams. It’s quite possible that this controversy won’t be actually resolved until the European Space Agency’s forthcoming GAIA mission.

So my take on this is that it’s a very interesting challenge to the orthodox theory, but the dark matter interpretation is far from dead because it’s not obvious to me that these observations would have uncovered it even if it is there. Moreover, there are alternative analyses (e.g. this one) which find a significant amount of dark matter using an alternative modelling method which seems to be more robust. (I’m grateful to Andrew Pontzen for pointing that out to me.)

Anyway, this all just goes to show that absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of absence…