I hope you’ve all been tuning in to the BBC’s astronomy jamboree Stargazing Live. There have been two episodes so far, with one last one to follow tonight, plus a huge range of activities across the country (including Wales) giving members of the public the chance to look at the sky through telescopes. The programmes and other activities have been getting an excellent response, especially from the younger generation, which is excellent news for the future of astronomy.

Working in a School of Physics & Astronomy makes one realise just how much public interest there is in astronomy, not just among schoolkids but in the numerous amateur astronomical societies, the members of which actually know the night sky better than many professionals! Most of us astronomers and astrophysicists are regularly asked to give public lectures and Cardiff in particular runs a host of other outreach activities related to our astronomy research. Our colleagues in mainstream physics subjects such as condensed matter physics don’t get the same level of direct public interest – I don’t think there are any amateur semiconductor physics clubs in the UK! – but many students attracted into universities by astronomy do turn to other branches of physics when they get here, because something else catches their imagination.

But important though that role is, let’s not forget that astronomy isn’t just about outreach. It’s actually real science, making real discoveries about the way our universe works. It’s worth doing in its own right as well as being good for other branches of physics.

Anyway, being a theoretical astrophysicist I usually feel a bit left out of these stargazing actitivies because I don’t really know one end of a telescope from the other. The other day I jokingly asked whether Stargazing Live was ever going to include a theory component…

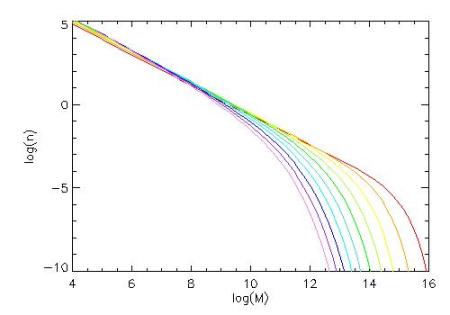

Last night’s episode actually did, in the form of a discussion of a numerical simulation of galaxy formation between the presenters and young Dr Andrew Pontzen from Oxford University. He even made a little video about the simulation, sort of virtual reality rendition of the formation of the Milky Way, as shown on the telly:

Apparently, making this required 300,000 CPU hours on 300 processors and it is based on 16 Terabytes of raw data. Phew!

It’s a very impressive simulation, but the use of the word simulation in this context always makes me smile. Being a crossword nut I spend far too much time looking in dictionaries but one often finds quite amusing things there. This is how the Oxford English Dictionary defines SIMULATION:

1.

a. The action or practice of simulating, with intent to deceive; false pretence, deceitful profession.

b. Tendency to assume a form resembling that of something else; unconscious imitation.

2. A false assumption or display, a surface resemblance or imitation, of something.

3. The technique of imitating the behaviour of some situation or process (whether economic, military, mechanical, etc.) by means of a suitably analogous situation or apparatus, esp. for the purpose of study or personnel training.

It’s only the third entry that gives the intended meaning. This is worth bearing in mind if you prefer old-fashioned analytical theory!

In football, of course, you can get sent off for simulation…

Follow @telescoper