Some years ago I came across a blog post relating to the discovery of a fortified settlement at Drumanagh (near Dublin) where Roman coins and goods have been found. It might have been a Roman military site, but in my mind it could equally well have been a Celtic settlement and the finds might have been loot from elsewhere.

I do find it a bit hard to believe that no Romans ever set foot in Ireland, though, and Drumanagh may well have been some sort of trading post or temporary fort for a reconnaissance mission. If that site is Roman, and that was all there was, then it didn’t amount to a full invasion and there’s certainly nothing like the roads or other infrastructure that’s so common in England and Wales.

I thought about this when at the weekend I was “reorganising” my bookshelves (by which I mean changing from one form of disorganization to another), when I came across some old Latin textbooks that included excerpts from the book De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae which was written by Publius Cornelius Tacitus (Tacitus to you). The Agricola of the title was Gnaeus Julius Agricola, Roman Governor of Britain from around AD 77 until 85. He also happened to be the father-in-law of Tacitus, which probably accounts for the sycophantic tone of some of the writing.

The availability of this book is interesting in itself because only a solitary codicil survived the Roman Era. It eventually became a very popular source in old-fashioned British grammar schools at which Latin was compulsory, as it was at the one I went to, partly because it related to Britain and partly because of the author’s very concise and direct prose which makes much of it quite easy to translate. We didn’t read the whole book at school, but excerpts cropped up regularly to illustrate various grammatical constructions and introduce new vocabulary.

You can find the full Latin text here and an English translation here. I tried Google translate on some passages and it was terrible.

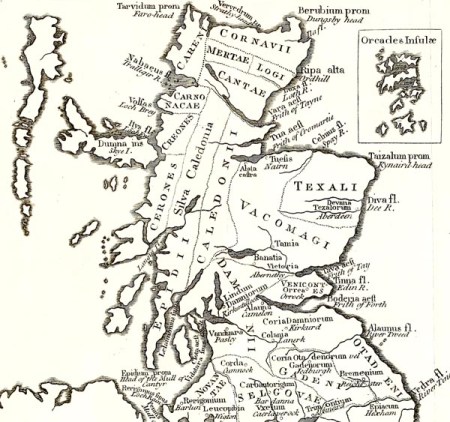

Anyway, as an exercise to my erudite readers I here include sections 23 to 26 which describe part of Agricola’s adventures in Scotland, followed by some comments. Before doing so it is worth mentioning a bit of the context. Agricola’s military campaigns at this time were often carried out in the first instance by water. Scotland was very much bandit country and slogging through the terrain on foot would have led to multiple ambushes and pitched battles.

[23] Quarta aestas obtinendis quae percucurrerat insumpta; ac si virtus exercituum et Romani nominis gloria pateretur, inventus in ipsa Britannia terminus. Namque Clota et Bodotria diversi maris aestibus per inmensum revectae, angusto terrarum spatio dirimuntur: quod tum praesidiis firmabatur atque omnis propior sinus tenebatur, summotis velut in aliam insulam hostibus.

[24] Quinto expeditionum anno nave prima transgressus ignotas ad id tempus gentis crebris simul ac prosperis proeliis domuit; eamque partem Britanniae quae Hiberniam aspicit copiis instruxit, in spem magis quam ob formidinem, si quidem Hibernia medio inter Britanniam atque Hispaniam sita et Gallico quoque mari opportuna valentissimam imperii partem magnis in vicem usibus miscuerit. Spatium eius, si Britanniae comparetur, angustius nostri maris insulas superat. Solum caelumque et ingenia cultusque hominum haud multum a Britannia differunt; [in] melius aditus portusque per commercia et negotiatores cogniti. Agricola expulsum seditione domestica unum ex regulis gentis exceperat ac specie amicitiae in occasionem retinebat. Saepe ex eo audivi legione una et modicis auxiliis debellari obtinerique Hiberniam posse; idque etiam adversus Britanniam profuturum, si Romana ubique arma et velut e conspectu libertas tolleretur.

[25] Ceterum aestate, qua sextum officii annum incohabat, amplexus civitates trans Bodotriam sitas, quia motus universarum ultra gentium et infesta hostilis exercitus itinera timebantur, portus classe exploravit; quae ab Agricola primum adsumpta in partem virium sequebatur egregia specie, cum simul terra, simul mari bellum impelleretur, ac saepe isdem castris pedes equesque et nauticus miles mixti copiis et laetitia sua quisque facta, suos casus attollerent, ac modo silvarum ac montium profunda, modo tempestatum ac fluctuum adversa, hinc terra et hostis, hinc victus Oceanus militari iactantia compararentur. Britannos quoque, ut ex captivis audiebatur, visa classis obstupefaciebat, tamquam aperto maris sui secreto ultimum victis perfugium clauderetur. Ad manus et arma conversi Caledoniam incolentes populi magno paratu, maiore fama, uti mos est de ignotis, oppugnare ultro castellum adorti, metum ut provocantes addiderant; regrediendumque citra Bodotriam et cedendum potius quam pellerentur ignavi specie prudentium admonebant, cum interim cognoscit hostis pluribus agminibus inrupturos. Ac ne superante numero et peritia locorum circumiretur, diviso et ipso in tris partes exercitu incessit.

[26] Quod ubi cognitum hosti, mutato repente consilio universi nonam legionem ut maxime invalidam nocte adgressi, inter somnum ac trepidationem caesis vigilibus inrupere. Iamque in ipsis castris pugnabatur, cum Agricola iter hostium ab exploratoribus edoctus et vestigiis insecutus, velocissimos equitum peditumque adsultare tergis pugnantium iubet, mox ab universis adici clamorem; et propinqua luce fulsere signa. Ita ancipiti malo territi Britanni; et nonanis rediit animus, ac securi pro salute de gloria certabant. Ultro quin etiam erupere, et fuit atrox in ipsis portarum angustiis proelium, donec pulsi hostes, utroque exercitu certante, his, ut tulisse opem, illis, ne eguisse auxilio viderentur. Quod nisi paludes et silvae fugientis texissent, debellatum illa victoria foret.

In [23], around 80 AD, we find that Agricola saw advantage in conquering Scotland as far as the Firth of Clyde (Clota) and Firth of Forth (Bodotria) because the tide would bring his ships a long way inland and they were separated by only a narrow stretch of land. He claims he would have gone further had he had the resources needed to do so.

[24] is the interesting one in light of the introduction to this piece . The fifth year of campaigning would have been 81 AD, long before the construction of Hadrian’s Wall. It says that Agricola crossed in his flagship (literally in the first ship, nave prima). It then goes to say that he garrisoned that part of Britain which faces Hibernia (i.e. Ireland) not out of fear but in hopes of further action. This is because he felt that Ireland offered a strategic connection between the provinces of Britain and Spain.

Some people think that the garrison Agricola formed for his putative future action, ostensibly an invasion of Ireland, was at Ravenglass in modern-day Cumbria, rather than Scotland, but it might have been further North; nobody really knows. My reading of the text is that he crossed the Firth of Clyde to the Mull of Kintyre. I remember as a kid seeing Ireland from the Mull of Kintyre and was told that on a clear day you could see as far as the mountains in Donegal from there.

Tacitus goes on to say that (my emphasis):

Ireland is smaller in size when compared to Britain, but larger than the islands of the Mediterranean. The soil, the climate and the character and manners of its inhabitants differ little from those of Britain, while its approaches and harbours are better known through trade and commerce. We also learn that Agricola has a friendly Irish chieftain in tow, who has been turfed out of his own land.

Agricola had given sanctuary to a minor chieftain driven from home by faction, and held him, under the cloak of friendship, until occasion demanded. My father-in-law often said that with one legion and a contingent of auxiliaries Ireland could be conquered and held; and that it would be useful as regards Britain also, since Roman troops would be everywhere, and the prospect of independence would fade from view.

So Agricola felt that people of Hibernia and Britain were similar and the effect of conquering the former would be to snuff out any hopes of independence in the latter. Either the planned invasion never happened, or Agricola tried it, got his fingers burnt and Tacitus chose to omit it from his account. This seems unlikely because Agricola had enough on his plate dealing with the Scottish campaign without diverting a legion to Ireland.

Anyway, the second emphasized section explains that Ireland’s ports were well known through trade and commerce, so one can infer that Romans were familiar enough to have landed there to trade, etc. I think Drumanagh was probably just one of many such stations.

In [25], a year later. Agricola is already campaigning beyond the Firth of Forth using a combination of naval and land-based forces. The Britons were wrong-footed by the Romans’ use of the sea, but mounted attacks against Roman forts. At the end of this section, Agricola, hearing that his force is about to be attacked, divides his army into three divisions and advances.

I included [26] because it mentions the Ninth Legion (in the accusative case, nonam legionem) because they are being attacked. The Ninth Legion has been the source of much speculation as the “Lost Legion”, as it disappears entirely from the historical record after about 120 AD. This unit was in the thick of the action, many times and was almost wiped out in 61 AD during the rebellion of Boudica and in other rebellions. According to Tacitus it was one of the three parts of Agricola’s army in 83 AD, though it was described as “especially weak” (maxime invalidem), and was in trouble there too, but was eventually rescued by the other two divisions. It doesn’t explain why the Ninth was the most weakened. Had it suffered more casualties than the rest of Agricola’s army or was it just not as well trained? Was part of it left as the garrison described in [24]? Could it have participated in an abortive invasion of Ireland the year before, got badly mauled in the process, and hadn’t recovered to full strength?

Bearing in mind that Tacitus wanted to portrary Agricola in a positive light, perhaps the complete rescue of the Ninth described in the text was exaggerated and its already weakened state was worsened still further by this battle? It wasn’t here that the Lost Legion was lost, however, as it cropped up elsewhere in Britain until at least 108 AD, twenty-five years later, and perhaps as late as 120 AD elsewhere on the continent. I’m not a historian but it seems to me that a plausible explanation of the fate of the Ninth Legion is that it was broken up into detachments and gradually dispersed, rather than being wiped out in one calamitous battle.