Alegoría del Invierno (Allegory of Winter) by Remedios Varo Uranga, 1948, gouache on paper, 44 ×44 cm, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain.

Alegoría del Invierno (Allegory of Winter) by Remedios Varo Uranga, 1948, gouache on paper, 44 ×44 cm, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain.

I was trying to find a work of art with which to illustrate the start of teaching term and decided on this remarkable painting by El Greco, usually called The Opening of the Fifth Seal though it has been given other names. Actually it’s only part of the original painting – the upper section was destroyed in 1880 – which at least partly accounts for the unusual balance of the composition. What I find astonishing about this work, though, is that at first sight it looks for all the world like an early 20th Century expressionist work, complete with distorted figures and vivid colour palette. It’s very hard to believe that it was painted in the early years of the 17th Century! El Greco was 300 years ahead of his time.

by Doménikos Theotokópoulos (“El Greco“), painted between 1608 and 1614, 224.8 cm × 199.4 cm, oil on canvas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

by Bridget Riley (1994, 1576 × 2278 mm, Oil on Canvas, Private Collection)

by Joan Miró (1940, gouache, watercolor, and ink on paper, 38cm × 46 cm, The Museum of Modern Art, New York City )

The famous portrait of Thomas Cromwell by Hans Holbein the Younger shown above is in fact a copy; the original is lost. There is another copy in the National Portrait Gallery in London, but it’s not as good. The original was painted around 1533, during the period covered by the novel Wolf Hall (which I reviewed yesterday) and is mentioned in the book. Holbein is known for having sometimes painted excessively flattering portraits – most notably of Anne of Cleves – but he doesn’t seem to have done that here. Cromwell is portrayed as dour, stern-faced and more than a little scary. He probably wanted people to fear him, so wouldn’t have minded this.

As well as the nature of the likeness, the composition is interesting. The subject seems to be squashed into the frame, and hemmed in by the table that juts out towards the viewer. He is also looking out towards the viewer’s left, though not simply staring into space; his eyes are definitely focussed on something. I’m not sure what all this is intended to convey, except that the table carries an ornate prayer-book (the Book of Hours) as if to say “look, here’s a symbol of how devout this man is”.

Interesting, just last year scholars published research that argues that the copy of the Hardouyn Hours which can be found in the Library at Trinity College, Cambridge, is precisely the book depicted on the table. If so, it’s a rare and perhaps unique example of an artefact seen in a Tudor painting that survives to this day.

Internazionale by Camille Souter (1965, 76.2 x 63.5 cm, oil on newsprint, private collection).

Posted in tribute to the artist, who has passed away at the age of 93.

R.I.P. Camille Souter (1929-2023).

The 17th-century Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) is famous not only as an artist but also for a particular style of facial hair, the goatee/moustache combo now known as a “Van Dyke”, as demonstrated by the man himself in this self-portrait:

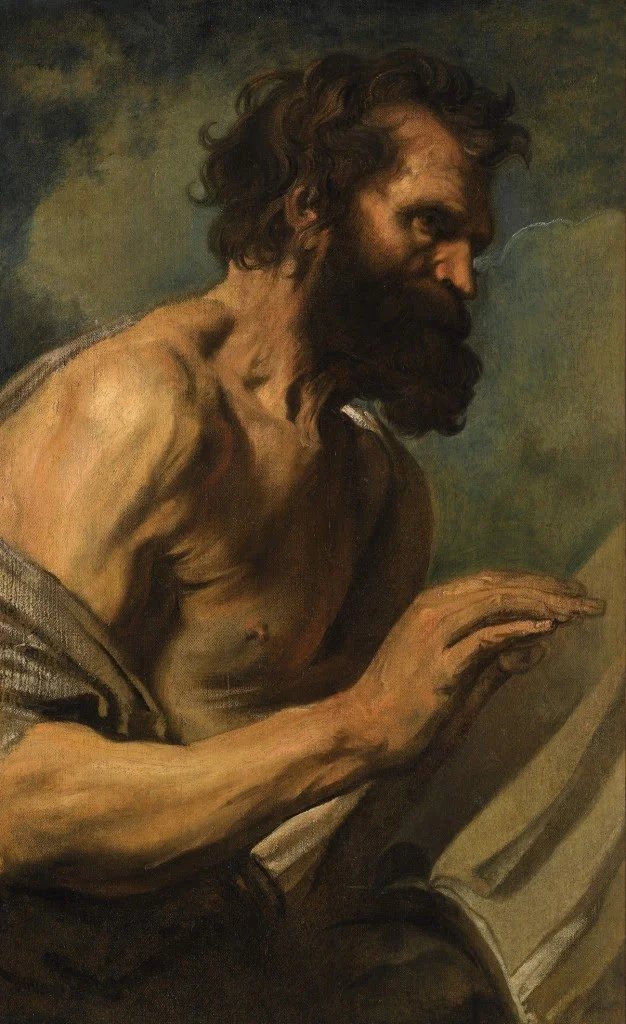

What I didn’t realise until recently however that van Dyck painted a very large number of studies of men with all kinds of beards. Here is a particularly fine example (Study of a Bearded Man with Hands Raised, 1616).

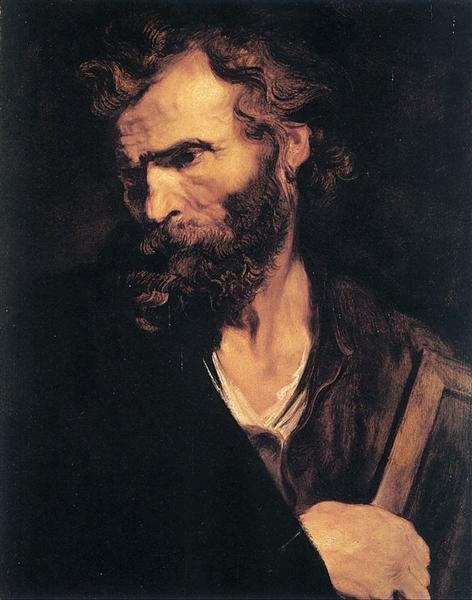

I’m not an expert but based on the poses I suspect these studies were done in preparation for paintings with biblical themes. Indeed the model looks rather similar to the figure in Jude The Apostle completed about three years later:

Back in Ireland on Thursday I was pottering about in my flat listening to the radio when I heard an interesting discussion about the work of art shown above, by Nathaniel Hone the Younger. It’s not a finished painting, but a small sketch made in watercolours, probably a study for a larger work. Hone made lots of these sketches over the years; this one was made in about 1890 at Kilkee and is in the National Gallery of Ireland. The dark palette and rough texture created by very thick application of the paint is unusual for a watercolour. No doubt all that is at least partly because of the windswept location in which the artist was working!

by Remedios Varo Uranga (1908-63), painted in 1945, 20 × 15.5cm, gouache on paper.