After a couple of boozy nights in Copenhagen during the workshop which has just finished, I thought I’d take things easy this evening and make use of the free internet connection in my hotel to post a short item about something I talked about at the workshop here.

Actually I’ve been meaning to mention a nice bit of statistical theory called Extreme Value Theory on here for some time, because not so many people seem to be aware of it, but somehow I never got around to writing about it. People generally assume that statistical analysis of data revolves around “typical” quantities, such as averages or root-mean-square fluctuations (i.e. “standard” deviations). Sometimes, however, it’s not the typical points that are interesting, but those that appear to be drawn from the extreme tails of a probability distribution. This is particularly the case in planning for floods and other natural disasters, but this field also finds a number of interesting applications in astrophysics and cosmology. What should be the mass of the most massive cluster in my galaxy survey? How bright the brightest galaxy? How hot the hottest hotspot in the distribution of temperature fluctuations on the cosmic microwave background sky? And how cold the coldest? Sometimes just one anomalous event can be enormously useful in testing a theory.

I’m not going to go into the theory in any great depth here. Instead I’ll just give you a simple idea of how things work. First imagine you have a set of observations labelled

. Assume that these are independent and identically distributed with a distribution function

, i.e.

Now suppose you locate the largest value in the sample, . What is the distribution of this value? The answer is not

, but it is quite easy to work out because the probability that the largest value is less than or equal to, say,

is just the probability that each one is less than or equal to that value, i.e.

Because the variables are independent and identically distributed, this means that

The probability density function associated with this is then just

In a situation in which is known and in which the other assumptions apply, then this simple result offers the best way to proceed in analysing extreme values.

The mathematical interest in extreme values however derives from a paper in 1928 by Fisher \& Tippett which paved the way towards a general theory of extreme value distributions. I don’t want to go too much into details about that, but I will give a flavour by mentioning a historically important, perhaps surprising, and in any case rather illuminating example.

It turns out that for any distribution of exponential type, which means that

then there is a stable asymptotic distribution of extreme values, as which is independent of the underlying distribution,

, and which has the form

where and

are location and scale parameters; this is called the Gumbel distribution. It’s not often you come across functions of the form

!

This result, and others, has established a robust and powerful framework for modelling extreme events. One of course has to be particularly careful if the variables involved are not independent (e.g. part of correlated sequences) or if there are not identically distributed (e.g. if the distribution is changing with time). One also has to be aware of the possibility that an extreme data point may simply be some sort of glitch (e.g. a cosmic ray hit on a pixel, to give an astronomical example). It should also be mentioned that the asymptotic theory is what it says on the tin – asymptotic. Some distributions of exponential type converge extremely slowly to the asymptotic form. A notable example is the Gaussian, which converges at the pathetically slow rate of ! This is why I advocate using the exact distribution resulting from a fully specified model whenever this is possible.

The pitfalls are dangerous and have no doubt led to numerous misapplications of this theory, but, done properly, it’s an approach that has enormous potential.

I’ve been interested in this branch of statistical theory for a long time, since I was introduced to it while I was a graduate student by a classic paper written by my supervisor. In fact I myself contributed to the classic old literature on this topic myself, with a paper on extreme temperature fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background way back in 1988..

Of course there weren’t any CMB maps back in 1988, and if I had thought more about it at the time I should have realised that since this was all done using Gaussian statistics, there was a 50% chance that the most interesting feature would actually be a negative rather than positive fluctuation. It turns out that twenty-odd years on, people are actually discussing an anomalous cold spot in the data from WMAP, proving that Murphy’s law applies to extreme events…

Follow @telescoper

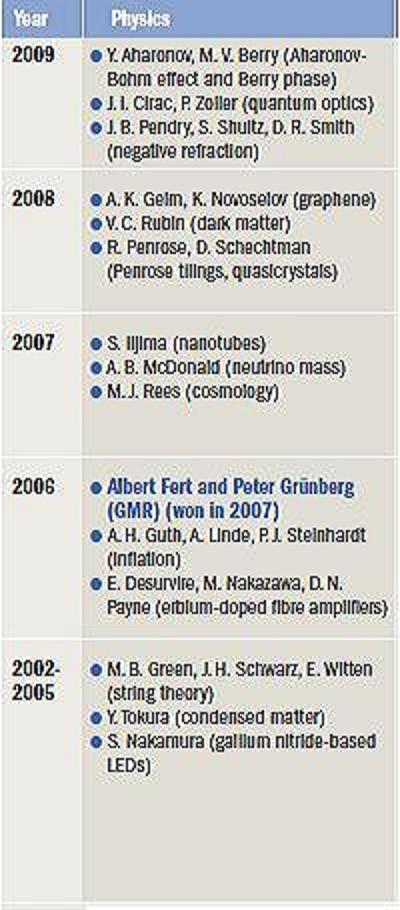

Initially the branch of physics most important to astrophysics was

Initially the branch of physics most important to astrophysics was