Trigger Warnings: Bayesian Probability and the Anthropic Principle!

Once upon a time I was involved in setting up a cosmology conference in Valencia (Spain). The principal advantage of being among the organizers of such a meeting is that you get to invite yourself to give a talk and to choose the topic. On this particular occasion, I deliberately abused my privilege and put myself on the programme to talk about the “Anthropic Principle”. I doubt if there is any subject more likely to polarize a scientific audience than this. About half the participants present in the meeting stayed for my talk. The other half ran screaming from the room. Hence the trigger warnings on this post. Anyway, I noticed a tweet this morning from Jon Butterworth advertising a new blog post of his on the very same subject so I thought I’d while away a rainy November afternoon with a contribution of my own.

In case you weren’t already aware, the Anthropic Principle is the name given to a class of ideas arising from the suggestion that there is some connection between the material properties of the Universe as a whole and the presence of human life within it. The name was coined by Brandon Carter in 1974 as a corrective to the “Copernican Principle” that man does not occupy a special place in the Universe. A naïve application of this latter principle to cosmology might lead us to think that we could have evolved in any of the myriad possible Universes described by the system of Friedmann equations. The Anthropic Principle denies this, because life could not have evolved in all possible versions of the Big Bang model. There are however many different versions of this basic idea that have different logical structures and indeed different degrees of credibility. It is not really surprising to me that there is such a controversy about this particular issue, given that so few physicists and astronomers take time to study the logical structure of the subject, and this is the only way to assess the meaning and explanatory value of propositions like the Anthropic Principle. My former PhD supervisor, John Barrow (who is quoted in John Butterworth’s post) wrote the definite text on this topic together with Frank Tipler to which I refer you for more background. What I want to do here is to unpick this idea from a very specific perspective and show how it can be understood quite straightfowardly in terms of Bayesian reasoning. I’ll begin by outlining this form of inferential logic.

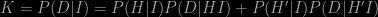

I’ll start with Bayes’ theorem which for three logical propositions (such as statements about the values of parameters in theory) A, B and C can be written in the form

where

This is (or should be!) uncontroversial as it is simply a result of the sum and product rules for combining probabilities. Notice, however, that I’ve not restricted it to two propositions A and B as is often done, but carried throughout an extra one (C). This is to emphasize the fact that, to a Bayesian, all probabilities are conditional on something; usually, in the context of data analysis this is a background theory that furnishes the framework within which measurements are interpreted. If you say this makes everything model-dependent, then I’d agree. But every interpretation of data in terms of parameters of a model is dependent on the model. It has to be. If you think it can be otherwise then I think you’re misguided.

In the equation, P(B|C) is the probability of B being true, given that C is true . The information C need not be definitely known, but perhaps assumed for the sake of argument. The left-hand side of Bayes’ theorem denotes the probability of B given both A and C, and so on. The presence of C has not changed anything, but is just there as a reminder that it all depends on what is being assumed in the background. The equation states a theorem that can be proved to be mathematically correct so it is – or should be – uncontroversial.

To a Bayesian, the entities A, B and C are logical propositions which can only be either true or false. The entities themselves are not blurred out, but we may have insufficient information to decide which of the two possibilities is correct. In this interpretation, P(A|C) represents the degree of belief that it is consistent to hold in the truth of A given the information C. Probability is therefore a generalization of the “normal” deductive logic expressed by Boolean algebra: the value “0” is associated with a proposition which is false and “1” denotes one that is true. Probability theory extends this logic to the intermediate case where there is insufficient information to be certain about the status of the proposition.

A common objection to Bayesian probability is that it is somehow arbitrary or ill-defined. “Subjective” is the word that is often bandied about. This is only fair to the extent that different individuals may have access to different information and therefore assign different probabilities. Given different information C and C′ the probabilities P(A|C) and P(A|C′) will be different. On the other hand, the same precise rules for assigning and manipulating probabilities apply as before. Identical results should therefore be obtained whether these are applied by any person, or even a robot, so that part isn’t subjective at all.

In fact I’d go further. I think one of the great strengths of the Bayesian interpretation is precisely that it does depend on what information is assumed. This means that such information has to be stated explicitly. The essential assumptions behind a result can be – and, regrettably, often are – hidden in frequentist analyses. Being a Bayesian forces you to put all your cards on the table.

To a Bayesian, probabilities are always conditional on other assumed truths. There is no such thing as an absolute probability, hence my alteration of the form of Bayes’s theorem to represent this. A probability such as P(A) has no meaning to a Bayesian: there is always conditioning information. For example, if I blithely assign a probability of 1/6 to each face of a dice, that assignment is actually conditional on me having no information to discriminate between the appearance of the faces, and no knowledge of the rolling trajectory that would allow me to make a prediction of its eventual resting position.

In tbe Bayesian framework, probability theory becomes not a branch of experimental science but a branch of logic. Like any branch of mathematics it cannot be tested by experiment but only by the requirement that it be internally self-consistent. This brings me to what I think is one of the most important results of twentieth century mathematics, but which is unfortunately almost unknown in the scientific community. In 1946, Richard Cox derived the unique generalization of Boolean algebra under the assumption that such a logic must involve associated a single number with any logical proposition. The result he got is beautiful and anyone with any interest in science should make a point of reading his elegant argument. It turns out that the only way to construct a consistent logic of uncertainty incorporating this principle is by using the standard laws of probability. There is no other way to reason consistently in the face of uncertainty than probability theory. Accordingly, probability theory always applies when there is insufficient knowledge for deductive certainty. Probability is inductive logic.

This is not just a nice mathematical property. This kind of probability lies at the foundations of a consistent methodological framework that not only encapsulates many common-sense notions about how science works, but also puts at least some aspects of scientific reasoning on a rigorous quantitative footing. This is an important weapon that should be used more often in the battle against the creeping irrationalism one finds in society at large.

To see how the Bayesian approach provides a methodology for science, let us consider a simple example. Suppose we have a hypothesis H (some theoretical idea that we think might explain some experiment or observation). We also have access to some data D, and we also adopt some prior information I (which might be the results of other experiments and observations, or other working assumptions). What we want to know is how strongly the data D supports the hypothesis H given my background assumptions I. To keep it easy, we assume that the choice is between whether H is true or H is false. In the latter case, “not-H” or H′ (for short) is true. If our experiment is at all useful we can construct P(D|HI), the probability that the experiment would produce the data set D if both our hypothesis and the conditional information are true.

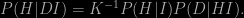

The probability P(D|HI) is called the likelihood; to construct it we need to have some knowledge of the statistical errors produced by our measurement. Using Bayes’ theorem we can “invert” this likelihood to give P(H|DI), the probability that our hypothesis is true given the data and our assumptions. The result looks just like we had in the first two equations:

Now we can expand the “normalising constant” K because we know that either H or H′ must be true. Thus

The P(H|DI) on the left-hand side of the first expression is called the posterior probability; the right-hand side involves P(H|I), which is called the prior probability and the likelihood P(D|HI). The principal controversy surrounding Bayesian inductive reasoning involves the prior and how to define it, which is something I’ll comment on in a future post.

The Bayesian recipe for testing a hypothesis assigns a large posterior probability to a hypothesis for which the product of the prior probability and the likelihood is large. It can be generalized to the case where we want to pick the best of a set of competing hypothesis, say H1 …. Hn. Note that this need not be the set of all possible hypotheses, just those that we have thought about. We can only choose from what is available. The hypothesis may be relatively simple, such as that some particular parameter takes the value x, or they may be composite involving many parameters and/or assumptions. For instance, the Big Bang model of our universe is a very complicated hypothesis, or in fact a combination of hypotheses joined together, involving at least a dozen parameters which can’t be predicted a priori but which have to be estimated from observations.

The required result for multiple hypotheses is pretty straightforward: the sum of the two alternatives involved in K above simply becomes a sum over all possible hypotheses, so that

and

If the hypothesis concerns the value of a parameter – in cosmology this might be, e.g., the mean density of the Universe expressed by the density parameter Ω0 – then the allowed space of possibilities is continuous. The sum in the denominator should then be replaced by an integral, but conceptually nothing changes. Our “best” hypothesis is the one that has the greatest posterior probability.

From a frequentist stance the procedure is often instead to just maximize the likelihood. According to this approach the best theory is the one that makes the data most probable. This can be the same as the most probable theory, but only if the prior probability is constant, but the probability of a model given the data is generally not the same as the probability of the data given the model. I’m amazed how many practising scientists make this error on a regular basis.

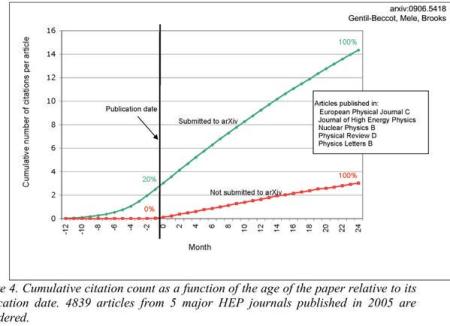

The following figure might serve to illustrate the difference between the frequentist and Bayesian approaches. In the former case, everything is done in “data space” using likelihoods, and in the other we work throughout with probabilities of hypotheses, i.e. we think in hypothesis space. I find it interesting to note that most theorists that I know who work in cosmology are Bayesians and most observers are frequentists!

As I mentioned above, it is the presence of the prior probability in the general formula that is the most controversial aspect of the Bayesian approach. The attitude of frequentists is often that this prior information is completely arbitrary or at least “model-dependent”. Being empirically-minded people, by and large, they prefer to think that measurements can be made and interpreted without reference to theory at all.

Assuming we can assign the prior probabilities in an appropriate way what emerges from the Bayesian framework is a consistent methodology for scientific progress. The scheme starts with the hardest part – theory creation. This requires human intervention, since we have no automatic procedure for dreaming up hypothesis from thin air. Once we have a set of hypotheses, we need data against which theories can be compared using their relative probabilities. The experimental testing of a theory can happen in many stages: the posterior probability obtained after one experiment can be fed in, as prior, into the next. The order of experiments does not matter. This all happens in an endless loop, as models are tested and refined by confrontation with experimental discoveries, and are forced to compete with new theoretical ideas. Often one particular theory emerges as most probable for a while, such as in particle physics where a “standard model” has been in existence for many years. But this does not make it absolutely right; it is just the best bet amongst the alternatives. Likewise, the Big Bang model does not represent the absolute truth, but is just the best available model in the face of the manifold relevant observations we now have concerning the Universe’s origin and evolution. The crucial point about this methodology is that it is inherently inductive: all the reasoning is carried out in “hypothesis space” rather than “observation space”. The primary form of logic involved is not deduction but induction. Science is all about inverse reasoning.

Now, back to the anthropic principle. The point is that we can observe that life exists in our Universe and this observation must be incorporated as conditioning information whenever we try to make inferences about cosmological models if we are to reason consistently. In other words, the existence of life is a datum that must be incorporated in the conditioning information I mentioned above.

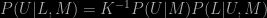

Suppose we have a model of the Universe M that contains various parameters which can be fixed by some form of observation. Let U be the proposition that these parameters take specific values U1, U2, and so on. Anthropic arguments revolve around the existence of life, so let L be the proposition that intelligent life evolves in the Universe. Note that the word “anthropic” implies specifically human life, but many versions of the argument do not necessarily accommodate anything more complicated than a virus.

Using Bayes’ theorem we can write

The dependence of the posterior probability P(U|L,M) on the likelihood P(L|U,M) demonstrates that the values of U for which P(L|U,M) is larger correspond to larger values of P(U|L,M); K is just a normalizing constant for the purpose of this argument. Since life is observed in our Universe the model-parameters which make life more probable must be preferred to those that make it less so. To go any further we need to say something about the likelihood and the prior. Here the complexity and scope of the model makes it virtually impossible to apply in detail the symmetry principles usually exploited to define priors for physical models. On the other hand, it seems reasonable to assume that the prior is broad rather than sharply peaked; if our prior knowledge of which universes are possible were so definite then we wouldn’t really be interested in knowing what observations could tell us. If now the likelihood is sharply peaked in U then this will be projected directly into the posterior distribution.

We have to assign the likelihood using our knowledge of how galaxies, stars and planets form, how planets are distributed in orbits around stars, what conditions are needed for life to evolve, and so on. There are certainly many gaps in this knowledge. Nevertheless if any one of the steps in this chain of knowledge requires very finely-tuned parameter choices then we can marginalize over the remaining steps and still end up with a sharp peak in the remaining likelihood and so also in the posterior probability. For example, there are plausible reasons for thinking that intelligent life has to be carbon-based, and therefore evolve on a planet. It is reasonable to infer, therefore, that P(U|L,M) should prefer some values of U. This means that there is a correlation between the propositions U and L in the sense that knowledge of one should, through Bayesian reasoning, enable us to make inferences about the other.

It is very difficult to make this kind of argument rigorously quantitative, but I can illustrate how the argument works with a simplified example. Let us suppose that the relevant parameters contained in the set U include such quantities as Newton’s gravitational constant G, the charge on the electron e, and the mass of the proton m. These are usually termed fundamental constants. The argument above indicates that there might be a connection between the existence of life and the value that these constants jointly take. Moreover, there is no reason why this kind of argument should not be used to find the values of fundamental constants in advance of their measurement. The ordering of experiment and theory is merely an historical accident; the process is cyclical. An illustration of this type of logic is furnished by the case of a plant whose seeds germinate only after prolonged rain. A newly-germinated (and intelligent) specimen could either observe dampness in the soil directly, or infer it using its own knowledge coupled with the observation of its own germination. This type, used properly, can be predictive and explanatory.

This argument is just one example of a number of its type, and it has clear (but limited) explanatory power. Indeed it represents a fruitful application of Bayesian reasoning. The question is how surprised we should be that the constants of nature are observed to have their particular values? That clearly requires a probability based answer. The smaller the probability of a specific joint set of values (given our prior knowledge) then the more surprised we should be to find them. But this surprise should be bounded in some way: the values have to lie somewhere in the space of possibilities. Our argument has not explained why life exists or even why the parameters take their values but it has elucidated the connection between two propositions. In doing so it has reduced the number of unexplained phenomena from two to one. But it still takes our existence as a starting point rather than trying to explain it from first principles.

Arguments of this type have been called Weak Anthropic Principle by Brandon Carter and I do not believe there is any reason for them to be at all controversial. They are simply Bayesian arguments that treat the existence of life as an observation about the Universe that is treated in Bayes’ theorem in the same way as all other relevant data and whatever other conditioning information we have. If more scientists knew about the inductive nature of their subject, then this type of logic would not have acquired the suspicious status that it currently has.